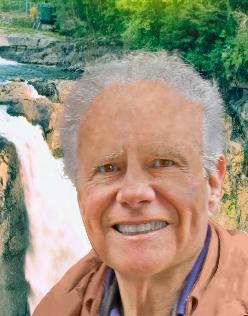

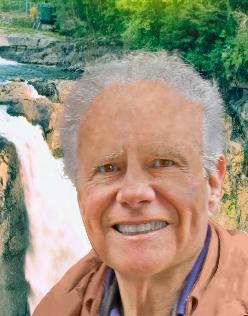

A guest blog today, from Judge Ralph Adam Fine, who has been sitting on Wisconsin’s Court of Appeals since 1988, and was a trial judge for 10 years before that. (And who hails from New York.) He’s the author of the How to Win Trial Manual, a lecturer on trial techniques, and an author of books on evidence, both federal and Wisconsin.

A guest blog today, from Judge Ralph Adam Fine, who has been sitting on Wisconsin’s Court of Appeals since 1988, and was a trial judge for 10 years before that. (And who hails from New York.) He’s the author of the How to Win Trial Manual, a lecturer on trial techniques, and an author of books on evidence, both federal and Wisconsin.

I asked him to pen this after a conversation I had with a federal court clerk, who told me that he continues to be stunned at the cluelessness of many lawyers that step into the well of the courtroom to try a case (often those from larger firms).

The skills below, of course, are things that Avvo is incapable of quantifiying.

And now, without further ado, a very short course on winning trial techniques…

———————————————————

The most important thing to remember when you’re trying to persuade a jury or a bench-trial judge is that you must make them see that you really believe in your client’s case—that justice is on your client’s side, whether your client is a person or an entity. Everything else, to paraphrase Rabbi Hillel’s observation about the golden rule, “is commentary”—as are these ten “commandments” and my book, The How-To-Win Trial Manual (Juris 5th rev. ed 2011). As Winston Churchill wrote when he was a young man, to persuade others, you, yourself, must believe, and that belief must shine out!

1. Your theme must resonate with what the jurors (or judge) knows from life; it must “ring true.

2. Give the jurors a simple solution and eschew law-school-instilled hyper-complexity. Jurors will apply Occam’s Razor to your case; do it for them with your theme, and you will win!

3. Do not argue inconsistent theories (I did not stab him but if I did it was self-defense) or present theories that are consistent so that they seem to be inconsistent (Wrong: She was not negligent, but even if she was, the defendant has overstated his injures. Right: She was not negligent, and, moreover, the defendant has overstated his injures.) Lesson: never use the phrase “but even if”!

4. Do not use your direct-examination witnesses (whether fact or “expert”) to elicit information or opinions. Rather, you must frame and ask your questions so that the jury (or judge) knows the answer before the witness responds. This way, the jury (or judge) will see the “truth” in your argument from the get-go and not have to rely on their assessment of the witness’s credibility—even a liar can say true things.

5. Do not use a lectern. You do not want to have anything between you and the persons to whom you are speaking, either the jury or judge. Yes, I know, some judges will not let you roam. If that’s the case in your trial, stand next to the lectern, but not behind it.

6. Do not read. The jury (or judge) must see you as the “truth-giver” in your trial. Truth-givers speak from their heart; they do not read. If you doubt this, consider whether you would read a prepared script when discussing something important with your significant other even though a missed phrase could be lethal. The jury (or judge) must see that you believe in what you’re saying and reading from a script, or relying on notes too much, prevents that.

7. Do not object in front of the jury either to the admission of evidence or to a question asked by your adversary. Truth-givers do not object because the truth cannot possible hurt them. If you cannot keep out evidence using a motion in limine, then you will have to deal with that evidence and make it work for you as a positive part of your proof! Trust me, this is not hard, as I show in my book and demonstrate in my workshops.

8. When arguing a matter before the judge (whether in front of the jury or when the jury is not there) never say that you are doing something “for the Record.” First, it is insulting to the judge because you are already telling the judge that you will be appealing. Second, and this is crucial, whenever you say “for the Record” the judge (or the jury if the jury is there) sees that you are just going through the motions and that you really do not believe in what you’re saying. Indeed, during my nine years as a trial judge, a little voice in me said “deny” whenever I heard a lawyer say that he or she was doing something “for the Record.” Other judges tell me they have similar reactions.

9. Do not rely on the burden of proof in your opening statement. First, the burden of proof in civil cases is essentially meaningless—a zillionth of an ounce on one side of an equally balanced scale is a “preponderance,” but no one would ever make a decision based on that difference. For lay people, something is either true or not true. In criminal cases, although the burden of proof is significant in closing argument, using it in your opening statement is counterproductive; when the jury hears that your client sits there “presumed” to be innocent and is “cloaked” by the constitution, most of them will see this as a concession that your client really did the things the prosecutor says your client did.

10. Finally (for this list), your “opening statement” must be an opening argument and can be so without being “argumentative.” Thus, you must put your personal credibility behind your client’s cause every time you speak to the jury, and no time is more important than in the beginning because if the jurors see from the get-go that truth and justice is on your side, they will root for you, and, using the tools of denial and rationalization, shunt aside your adversary’s evidence. Thus, instead of the bland and neutral, “the evidence will show” x and y, you must say something like, “I will prove” x and y. That is not “argumentative” because you could have just as easily used the less-persuasive “evidence will show.” Something is “argumentative” when you cannot make that substitution, as in “send them a message” or some such exhortation.

Last week I was on trial — at three days it was the shortest one I ever had — and my trial prep included this: Deleting any Twitter messages that were political. My first post on Twitter was thee years ago, January 29, 2009. Since then I have made about 800+ posts.

Last week I was on trial — at three days it was the shortest one I ever had — and my trial prep included this: Deleting any Twitter messages that were political. My first post on Twitter was thee years ago, January 29, 2009. Since then I have made about 800+ posts.

I looked in my RSS feed and saw 4,000 unread posts. Yeah, I know that’s a lot. If the blogosphere thinks I fell off the face of the earth because my posts are a bit less frequent lately, I assure you that those in my community know otherwise.

I looked in my RSS feed and saw 4,000 unread posts. Yeah, I know that’s a lot. If the blogosphere thinks I fell off the face of the earth because my posts are a bit less frequent lately, I assure you that those in my community know otherwise.