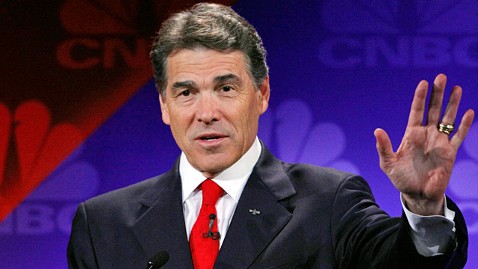

There was something deeply troubling about the reaction to Texas Gov. Rick Perry’s brain fart the other night during the Republican presidential debate. He said he wanted to whack three different federal agencies — Education, Commerce and Energy, but couldn’t remember Energy in the glare of the lights and pressure of the moment. He froze, and people have been yapping about the freeze ever since.

There was something deeply troubling about the reaction to Texas Gov. Rick Perry’s brain fart the other night during the Republican presidential debate. He said he wanted to whack three different federal agencies — Education, Commerce and Energy, but couldn’t remember Energy in the glare of the lights and pressure of the moment. He froze, and people have been yapping about the freeze ever since.

In chattering about the freeze, of course, commentators mostly missed the opportunity to talk about the substance of what he was proposing. The superficial trumped the substance. Yes, I know this happens all the time in politics, as it is easy for everyone to talk about a brain freeze while it might take some real thinking to discuss substance.

I felt bad for Perry, even though he isn’t my cup of tea. Anyone who talks in public — and trial lawyers do this so that is where I am going with this post — knows that this can happen. That’s why we work from notes.

But working from notes necessitates striking a balance. Because you never want to read to a jury or an appellate bench, unless you have to exactly quote something. If you put your nose in your notes, you lose the attention of the listener. So more notes means less likely to forget something, but also the danger of losing your audience. And vice versa. This is Trial Practice 101.

So we try to strike that happy balance. For me, when I open to a jury or make an appellate argument I try hard to use a rough outline that does not exceed one page, 14 point type. I use it to glance at. Summations are similar, except that I will read a few trial transcript bits to the extent I think critical. And I always apologize to the jury for reading.

In cross-examination, of course, you have to wrestle not only with what you want to bring out to the jury, but with what the witness is trying to do. Notes become even harder to use in that situation. And it is easy to lose a train of thought and suffer the dreaded brain fart when dealing with the subject matter, the witness, the form of and the question. You need to focus on the big picture and the nitty gritty at the same time, as well as the next line of questioning that you want to lead the witness to. Yeah, that takes practice.

Which brings me back to Perry. When you walk on a high wire those kinds of flubs can happen. But I wouldn’t want a juror to judge my case if it happened to me, and I don’t think folks should judge Perry based on his. Critique the substance, not the style.

Of course, if the points are really, really important, you might want to follow the Sarah Palin method, and write them down on your hand.

Of course, if the points are really, really important, you might want to follow the Sarah Palin method, and write them down on your hand.

I think I’ll file this one under Trial Practice.

I am struck by how a simple brain fart, of the sort that happens to everyone from time to time, is what has people declaring Perry’s candidacy dead. This shows the power of a media narrative. Under ordinary circumstances a brain fart is overlooked since, after all, they happen to everyone so everyone knows that they aren’t particularly meaningful. In the case of Perry, however, the media narrative that has developed since he declared his candidacy is that he isn’t very bright. This brain fart feeds into this media narrative, and so serves as Deeply Significant confirmation of the narrative.

On the other hand, he apparently really isn’t very bright. Even his supporters often tacitly acknowledge this. So I can’t feel too sorry for him.

I agree that we should not hold Mr. Perry’s brain fart against him. Brain farts happen. It is the substance of Mr. Perry’s campaign that people should find offensive. His plan for America stinks.

Unfortunately, those lapses in concentration (commonly known as a brain fart) always seem to happen at the moist inopportune moments. the best thing to do is acknowledge it (it happens to everyone), take a moment to compose yourself, and get back on topic. If you pull a “Perry” you hurt your credibility.