The story of ambulance chasing after the Hulk Hogan case is buried 22 paragraphs into the New York Times article. But that is where I am going today.

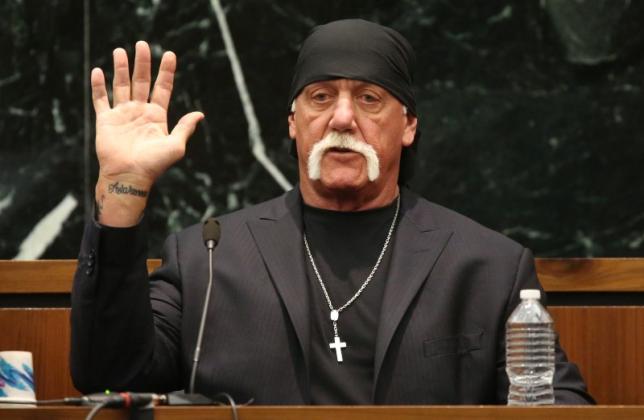

As many of you know, Terry Bollea (a/k/a Hulk Hogan), sued Gawker over the release of a sex tape that was made with the wife of his (former) good friend. The jury came back with a whopping $140M verdict.

There were two pieces of news on the case: First, the trial judge didn’t reduce the damages. Nor was the case tossed out on First Amendment grounds. Both of those issues, for sure, will be on appeal, though Gawker must post a $50M bond to get there, which may bankrupt the website.

But that news is well covered elsewhere. So too was the news that Silicon Valley billionaire Peter Thiel was bankrolling the lawsuit. Thiel, it seems, has a personal vendetta against Gawker dating to the time that it outed him as gay on its Valleywag blog.

Don’t worry, I’m going to get to the part about the ambulance chasing, just as soon as I finish bringing you up to speed on motivation:

From yesterday’s New York Times, where Thiel gives his first interview on the subject, he said:

“It’s less about revenge and more about specific deterrence,” he said on Wednesday in his first interview since his identity was revealed. “I saw Gawker pioneer a unique and incredibly damaging way of getting attention by bullying people even when there was no connection with the public interest.”

Mr. Thiel said that Gawker published articles that were “very painful and paralyzing for people who were targeted.” He said, “I thought it was worth fighting back.”

OK, and from motivation we move on to funding lawsuits. Litigation finance is big business as it may be difficult (or impossible) for clients or lawyers of modest means to bring suits without being able to pay experts and other costs. They are generally frowned upon by lawyers as a last ditch effort to continue, due to the very high financing charges. But if needed they do level the playing field when litigating against insurance companies and other well-financed companies.

These finance companies come in at the request of counsel.

So the New York Times finds it important to get a couple of law professors (at least one of which has apparently never set foot in a courtroom or even been admitted to practice law) to dutifully quote in order to make it looks like “experts” have weighed in:

“If you really do have concerns about the merits of this case, finding out who bankrolled it doesn’t really help you at all,” said Mary Anne Franks, a professor at the University of Miami School of Law. Absent any indication that there is something unlawful about how the funding took place, she said, “you would still need to show that there’s something substantively wrong with the ruling.”

But Thiel was a different sort of financier — he went looking for the client.

Thiel tells how he solicited the case, and claimed this was normal:

He said that he hired a legal team several years ago to look for cases that he could help financially support. “Without going into all the details, we would get in touch with the plaintiffs who otherwise would have accepted a pittance for a settlement, and they were obviously quite happy to have this sort of support,” he said. “In a way very similar to how a plaintiff’s lawyer on contingency would do it.” Mr. Thiel declined to disclose what other cases he had supported but there are at least two current cases against Gawker.

A couple things here: First, this is not “very similar” to how a plaintiff’s lawyer on contingency works. Because what he did is solicitation, and the vast, vast majority of lawyers do not contact victims. Solicitation is ambulance chasing.

The second issue, and the reason I write today, is that there is a parallel here to the issue of non-attorneys owning part of a law firm, a matter that has been discussed in various jurisdictions (and which is, thankfully, not allowed in New York).

Non-attorneys owners, after all, are only needed for their money to fund cases and overhead.

While profit is not the motive for Thiel in the Hulk Hogan case (he positions this as a public interest lawsuit), this case is an outlier. But this particular outlier, has important lessons.

This particular funding case — where the funder solicited the client — is an example of what will happen if you allow non-lawyers to have ownership of law firms. They will solicit. When the plane goes down, when the bus crashes, when the horror hits the front page, the non-lawyer owner may go hunting for business. I wrote about this twice before, both in 2011:

North Carolina to Allow Non-Lawyers to Buy Interest in Firms? (Lousy Idea)

Jacoby & Meyers Sues To Sell Themselves to Non-Lawyers (Lousy Idea)

While New York has a 30-day anti-solicitation rule after a mass disaster, non-lawyers are not bound by Rules of Professional Conduct. And if they we allowed non-lawyer ownership, and they were told to comply with the Rules, what happens when they violate it? Disbarment? The non-lawyer does not lose his livelihood. And his lawyer partners would no doubt say, “Oh my lord! We had no idea!!!” And like that, an intentional ethical violation is downgraded to mere negligence.

So Peter Thiel, in his solicitation of Hulk Hogan, shows the potential future of law if non-attorneys are allowed in the door to own parts of law firms: They will have a vested interest in getting the case, and their solicitations will be to the detriment of the bar’s reputation and the public’s faith in the justice system.

If/when someone feels the need to reach out for counsel, there are plenty of ways to do it. But reaching in, while a family is in shock or grieving, is a recipe for inviting in hustlers and con artists, and seeing people victimized a second time.