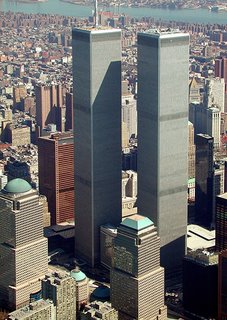

A jury’s finding of liability has been upheld by a New York appellate court against the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey regarding the 1993 terrorist attack. The attack killed six and injured about 1,000 others. The jury found the PA to be 68% liable in the attack for its negligence in failing to provide security in the face of a clear danger that the trade center was a terrorist target. Since the finding of liability exceeded 50%, under New York law they are liable to pay all of the non-economic damages.

A jury’s finding of liability has been upheld by a New York appellate court against the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey regarding the 1993 terrorist attack. The attack killed six and injured about 1,000 others. The jury found the PA to be 68% liable in the attack for its negligence in failing to provide security in the face of a clear danger that the trade center was a terrorist target. Since the finding of liability exceeded 50%, under New York law they are liable to pay all of the non-economic damages.

The decision by the Appellate Division First Department in Nash v. Port Authority followed long established premises liability law as it pertains to the reasonable security measures that landlords must undertake to make their premises safe. In essence, if one follows the opinion, the case was little different then that of a crime being committed in an apartment house after a broken lock went unfixed for months on end.

The court’s analysis started with some very fundamental issues regarding the well known risk that the trade center was a terrorist target, recounting the Port Authority’s own security report that found it was “obvious that the potential for a terrorist attack upon the World Trade Center is a real possibility and [that] the results could be catastrophic,” and specifically noted that “[t]he parking lots are accessible to the public and are highly susceptible to car bombings.” Another report, according to the court,

found that “it was not merely possible, but “probable,” that there would be an attempt to bomb the World Trade Center and pointedly noted, “the WTC is highly vulnerable through the parking lot . . . With little effort terrorists could create havoc without being seriously deterred by the current security measures.”

And yet another report found that “Parking for 2,000 vehicles in the underground areas presents an enormous opportunity, at present, for terrorists to park an explosive filled vehicle that could affect vulnerable areas.” The report became still more specific in describing the feared scenario:

“A time bomb-laden vehicle could be driven into the WTC and parked in the public parking area. The driver could then exit via elevator into the WTC and proceed with his business unnoticed. At a predetermined time, the bomb could be exploded in the basement. The amount of explosives used will determine the severity of damage to that area.”

With respect to the duty that the Port Authority, as landlord, owed to the tenants and visitors of the trade center, the court rejected the absurd defense claim that, because no such attack had taken place previously, they had no duty to prevent against one. The court noted that:

it is fair to say that no reasonably prudent landlord, aware as defendant was of the value of his or her structure as a terrorist target and of a specifically identified condition upon the property rendering it vulnerable to terrorist penetration, would await a terrorist attack, particularly one directed at basic structural elements, before undertaking, to the extent reasonably possible, to minimize the risk.

Thus, the reports (and these are just a few that I quoted from the court’s opinion) clearly gave notice to the Port Authority of the danger, and it had a duty to act on that danger. In premises liability law well known to New York’s personal injury attorneys — familiar from other breach of security cases such as those that take place with broken locks in apartment buildings and subsequent crimes — the court wrote (citations omitted) of the duty of landlords, that they must

“act as a reasonable [person] in maintaining his [or her] property in reasonably safe condition in view of all the circumstances, including the likelihood of injury to others, the seriousness of the injury, and the burden of avoiding the risk. This ultimate standard is as applicable in premises security cases as it is in other contexts where liability is sought as against a landowner for injuries allegedly attributable to premises hazards or defects. Indeed, it has been observed that the duty of a landlord to take reasonable measures to minimize foreseeable danger on his or her premises from third-party criminal activity is but a natural corollary to the landowner’s common-law duty to make the public areas of his property reasonably safe for those who might enter.

It is true, of course, that a landlord is not an insurer of the safety of those upon his or her property and that the actual precautions sufficient to meet the reasonable care standard in premises security actions have often been described as “minimal.” This is, in the vast majority of cases, a perfectly accurate description of the property owner’s obligation; ordinarily, a landlord has discharged his or her duty if the basic perimeter and public area security systems, such as locks, buzzers, intercoms and lighting, are properly installed and maintained. The legally binding standard of care, as distinguished from the particular precautions required for its satisfaction in a given case, however, remains reasonable care to render the premises reasonably safe, and there are circumstances in which the nature and likelihood of a foreseeable security breach and its consequences will require heightened precautions…”

So what did the PA do in response to this danger? Apparently nothing. And the court was pretty clear that the jury was fully justified in making a 68% finding of liability against it after listening to the evidence, even though the PA was the negligent tortfeasor (as opposed to the intentional tortfeasor whose attack was predicted):

This was not a case in which ordinary negligence was transformed into a precipitant of tragedy by an otherwise unrelated, merely coincidental intentional act, but one in which the intentional act was foreseeably responsive to and exploitative of the negligence and, causally, did little more than bring the incipient catastrophic potential of the negligence to terrible fruition.

In seeking to avoid this entirely justifiable construction of the evidence, defendant sought to portray the bombers as exceedingly determined and clever malefactors, whose success was attributable, not in the main to its negligence, but to their own “finely tuned” plan. It would, however, have been very difficult to convince any jury that a “finely tuned” plan was necessary to do what the bombers did. There was evidence before the jury that explosives in “envisioned quantities” were readily available and that, once the explosives had been obtained and loaded onto the rented van, all that remained between the bombers and their nefarious objective were tasks rendered horrifyingly and embarrassingly simple by defendant’s negligence: driving the van into the complex’s subgrade parking facility, parking on the access ramp, setting a fuse and leaving the scene – all with evident ease. Only the most rudimentary plan was needed to take advantage of the “enormous opportunity” that defendant had through its negligence provided.

The court was clear that the law here is not about “comparative reprehensibility” — for there is no doubt that the terrorists’ conduct would warrant vacatur of the award if that was the standard — but rather, about the conduct that contributed to the harm.

Did the court absolve the terrorists with this decision? Of course not. And what’s more, they fully anticipate such criticism:

The verdict we now uphold is neither properly nor intelligently understood as absolving the terrorists. The issue before the jury in this civil action was not whether the terrorists had committed the bombing — obviously they had — or whether they should be severely penalized — most of them were — but whether their heinous conduct was foreseeable and avoidable by defendant in the discharge of its proprietary responsibilities.

In sum:

- There was as duty of care by the Port Authority due to the forseeable risk of a terror attack;

- The Port Authority breached that duty of care;

- That breach was as a substantial factor in causing injury;

- The jury apportioned fault based upon the conduct of the people involved, as opposed to apportioning based on moral turpitude.

And a last word from the court on whether the Port Authority should be immune from suit:

[T]he evidence overwhelmingly supported the view that the conscientious performance of defendant’s duty reasonably to secure its premises would have prevented the harm. This civil jury had no power to decide whether the terrorists should in any meaningful sense be “absolved” of their murderous acts. What it could and did decide was rather that the acts of these terrorists, even while obviously odious in the extreme, were not a cause for the easy absolution of this defendant from its civil obligations.

For anyone trying a failed security that allows a criminal on the premises to commit a crime, this case is a must-read.

See also:

- From the defense side, see Ted Frank at Overlawyered who thinks the Port Authority should get a free pass for its negligence)