I know, you’ve been sitting there on the edge of your seat waiting for this, ever since I discussed the serious lack of private practice work by Elena Kagan. Which wouldn’t be so bad except that only Justice Kennedy seems to have had any private practice experience. Basically, 98% of the legal time for Supreme Court justices has been in academia or public service.

I know, you’ve been sitting there on the edge of your seat waiting for this, ever since I discussed the serious lack of private practice work by Elena Kagan. Which wouldn’t be so bad except that only Justice Kennedy seems to have had any private practice experience. Basically, 98% of the legal time for Supreme Court justices has been in academia or public service.

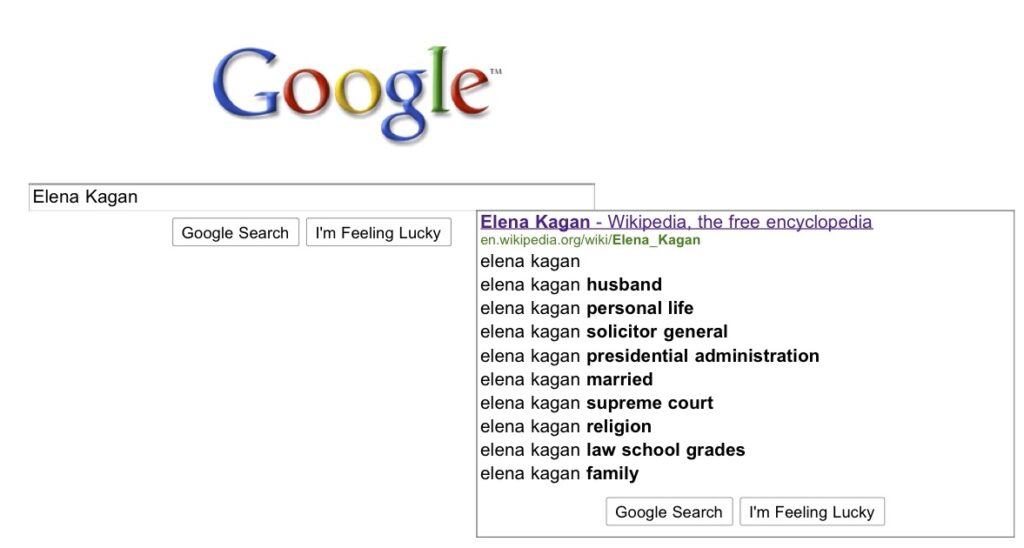

So Kagan’s Senate Judiciary questionairre was released, and with drool running from my mouth I searched for all that I could on her private practice — much as I did with Sonia Sotomayor when I found her little private firm, Sotomayor & Associates that had no actual associates and subsequently became a minor issue.

And it turns out, while at the BigLaw firm of Williams & Connolly between 1989 and 1991, Kagan actually did some First Amendment work that was interesting. In fact, of the 10 “most significant litigated matters which you personally handled” that the the Senate Judiciary Committee asked her to list, five had to do with the First Amendment. And, despite being a very junior associate, she was actually given the chance to argue a couple of times in court.

[Note, Eugene Volokh has written about her First Amendment scholarship that followed the years of private practice. This post is only about the real-world experience that preceded it. A full round-up of her career, including scholarship but missing the real-world stuff, is at SCOTUSblog]

OK, here is the set-up — you’re sitting down, right? — on page 71…

I have had private clients only during the time I was an associate at Williams & Connolly. Those clients included business entities in civil litigation, press organizations defending themselves in libel and related actions, and white- collar criminal defendants.

She goes on to write that her private work was “primarily” in federal court and that it was divided 2/3 to civil and 1/3 to criminal. She concedes having never tried a case to verdict. That wouldn’t be so bad, of course, if the high court had others that had done so for private individuals.

Now to the meat and potatoes: On pages 188-195 she is asked to “Describe the ten (10) most significant litigated matters which you personally handled, whether or not you were the attorney of record.” As you can see below, some of this stuff is anything but interesting, which gives a bit of insight perhaps in to what happens to junior associates at BigLaw firms.

So here is Elena Kagan’s Top 10 List of private cases. The First Amendment ones can be seen below as d-h. (I’ve listed all 10, in case people find any of the other stuff interesting — two are criminal matters):

(a) Federal Realty Investment Trust v. Pacific Insurance Co., No. R-88-3658. We represented a real estate investment trust in an action against an insurer for the costs of defense associated with a prior litigation. I began work on the case in the middle of the litigation; I did some late discovery and drafted most of the pre-trial motions. On the eve of trial, Judge Norman Ramsey of the U.S. District Court for the District of Maryland ruled in favor of our position on the appropriate standard for allocating defense costs between covered and uncovered parties and claims (760 F. Supp. 533 (1991)). This ruling immediately produced a settlement favorable to our client.

(b) In re Seatrain Lines, Inc., Nos. 81 B 10311, 81 B 10916, 81 B 11059, 81 B 12345, 81 B 12525, 81 B 11845, 81 B 11004, 81 B 11512. We represented Seatrain Lines, Inc., a debtor in bankruptcy, in U.S. Bankruptcy Court in the Southern District of New York (Judge Burton Lifland presiding) in connection with an application by Chase Manhattan Bank and Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy for legal fees associated with the bankruptcy case. In response to the filing of the fee application, our client counterclaimed against Chase for the recovery of the costs of preserving and disposing of certain properties subject to Chase’s security interest. I handled some of the discovery and drafted most of the pleadings. When the court denied Chase’s motion to strike our counterclaim (and a subsequent motion for reconsideration), the parties settled on terms favorable to our client.

(c) Toyota of Florence, Inc. v. Lynch, Nos. 4-89-594-15, 4-89-595-15. We represented Southeast Toyota Distributors, Inc. in a suit brought by one of its franchisees alleging fraud, intentional interference with contract, violations of RICO, and a host of other claims. I drafted numerous pleadings in the case, including an opposition to the plaintiff’s motion to remand (granted by Judge Hamilton of the U.S. District Court for South Carolina at 713 F. Supp. 898 (1989)), as well as motions to dismiss and discovery motions (ruled on by Judge Edwin Cottingham of the Court of Common Pleas for Darlington County). I also handled some of the discovery. I left the firm prior to trial. Ultimately, a verdict for the plaintiff was dismissed on appeal.

(d) Byrd v. Randi, No. MJG-89-636. We represented defendant Montcalm Publishing Corp. in a libel action arising from an allegation that the plaintiff was in prison for child molestation. The case presented issues relating to the “libel-proof plaintiff” doctrine, the definition of a “limited purpose public figure,” and the actual malice standard. I did most of the discovery, drafted our summary judgment motion and other pleadings, and argued the summary judgment motion before the district court. After initially denying the motion, Judge Marvin Garbis of the U.S. District Court for the District of Maryland dismissed the case a few months later on a motion for reconsideration.

(e) In Re Application of News World Communications, Inc., Nos. 89-3160, 89-212. We represented the Washington Post and WRC-TV in this effort to compel release to the public of unredacted transcripts of audiotapes to be received in evidence at a criminal trial. I argued motions before Judge Charles Richey of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia to compel release of the transcripts and to prevent redaction. Judge Richey granted both motions, with the latter reported at 17 Media L. Rep. 1001 (1989). The Court of Appeals for the D. C. Circuit, with Judges Wald, Silberman, and Sentelle hearing argument, denied a motion to stay this order (17 Media L. Rep. 1004 (1989)).

(f) J. Odell Anders v. Newsweek, Inc., No. 90-715. We represented Newsweek, Inc. on appeal from a jury verdict in its favor in a libel action filed in the Southern District of Mississippi. The case raised questions about the actual malice standard, as well as numerous evidentiary issues. I drafted the appellate brief urging affirmance. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit held in our favor by unpublished opinion (judgment reported at 949 F.2d 1159 (1991)).

(g) Luke Records, Inc. v. Nick Navarro, No. 90-5508. We filed an amicus brief in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit on behalf of the Recording Industry Association of America and numerous record companies, challenging the decision of the district court that a musical recording was obscene under the standard set forth by the Supreme Court in Miller v. California. I drafted the brief in the case, which stressed the difficulty of holding music obscene under prevailing constitutional law. Judge Lively, joined by Judges Anderson and Roney, reversed the district court’s decision (960 F.2d 134 (1992)).

(h) Bagbey v. National Enquirer, No. CV 89-2177. We represented the National Enquirer in this libel action brought by a person mistakenly identified in the publication as being Jimmy Swaggert’s father. I drafted all pleadings and did all discovery in the case, which began in Louisiana state court but which we removed to the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Louisiana (Judge F.A. Little, Jr.). We eventually settled the case on terms favorable to our client.

(i) Chuang v. United States, No. 89-1309. We represented Joseph Chuang, a former bank president, on his appeal from a criminal conviction for numerous counts of bank fraud. The principle issues in the case concerned the propriety of two warrantless searches of the bank, one by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and one by the FDIC. I drafted most sections of the brief, which argued among other matters (1) that the statute authorizing the OCC’s search failed to provide a constitutionally adequate substitute for a warrant, as required by the Supreme Court, and (2) that the FDIC’s search was invalid because it went beyond the bank premises into Chuang’s law firm offices. The Second Circuit affirmed the conviction, with Judge Timbers writing and Judges Newman and Altimari joining (897 F.2d 646 (1990)).

(j) United States v. Jarrett Woods, We represented the former head of the Western Savings Association, a failed savings and loan, in both a grand jury investigation and a number of civil suits brought against him. The Federal Home Loan Bank Board had declared the S&L insolvent and placed it in receivership after discovering various suspect real estate loans. In addition to trying to keep the civil suits at bay, we tracked the grand jury investigation of Woods closely for more than a year – interviewing each of the many people brought before the grand jury – before Woods became unable to afford the representation. Woods was subsequently indicted and convicted of numerous counts of bank fraud.

So I was all prepared to say that we were about to put on the Supreme Court another person without any real private practice experience at all. But, in fact, she has a very small amount. Nothing earth shattering for sure, but a tiny amount nonetheless.

One quirk I noticed in (h), Bagbey v. National Enquirer: She says that “We eventually settled the case on terms favorable to our client.” I wonder if there was a non-disclosure agreement regarding that settlement, and if so, if her comments about settling on “favorable” terms violated it.

Update: I could see how some Senators might review some of her First Amendment briefs, which should be publicly available in court files, to inquire as to whether she actually believed in some of the positions that she took. That could put her on the spot to either defend, or distance, herself from a position that she advocated.

Update x2 — Elsewhere:

- Kagan’s First Amendment record causes concern (David L. Hudson, Jr. @ First Amendment Center)

- Who Gets the Gag? Elena Kagan’s First Amendment Problem (Gary Bauer @ Human Events)

- Elena Kagan v. First Amendment (Chicago Sun Times)

- Elena Kagan vs. that bothersome First Amendment thing (Jack Hentoff @ Jewish World Review)