Did you ever want to go racing along rural roads in New Hampshire at 2 a.m., guided only by a headlamp, some signs, and the blinking butt-light of others? And several miles later you get to climb into a van full of other sweaty, smelly runners wanting to do the same thing? I thought so.

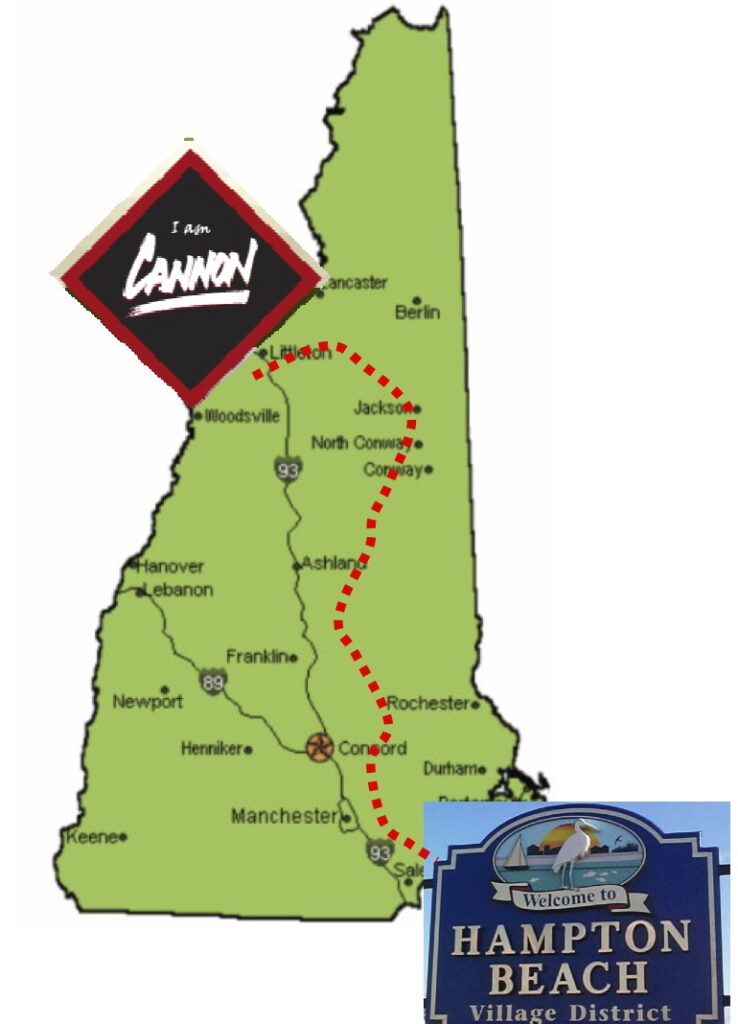

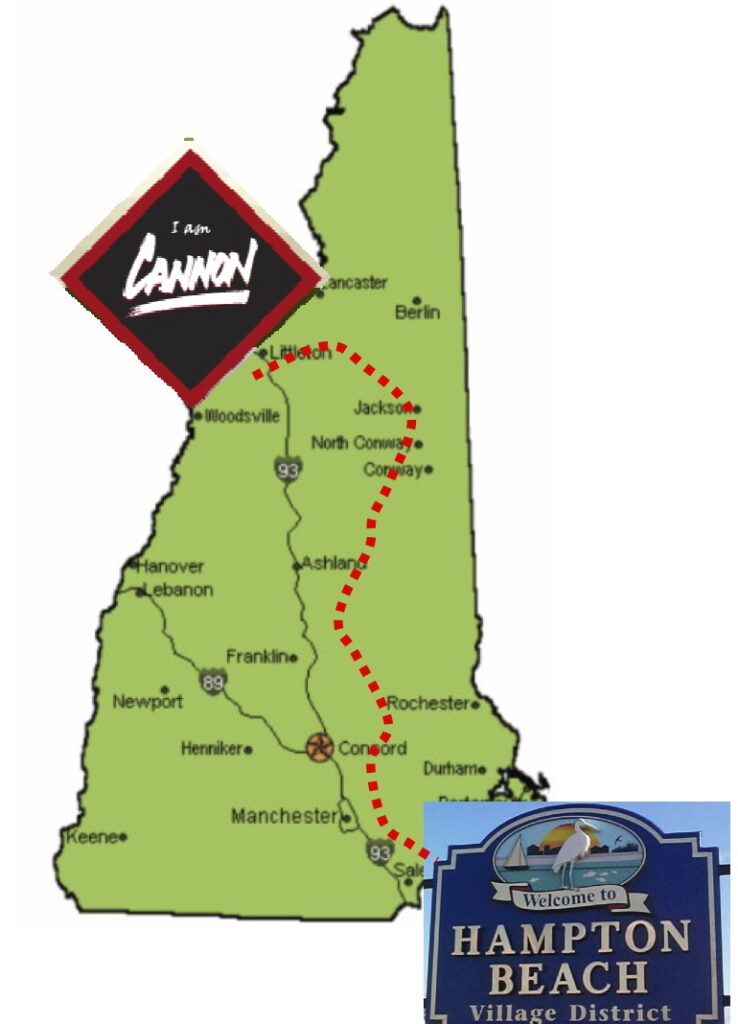

You can see a map of the 200-mile race course of the Reach the Beach Relay to the right, starting at Canon Mountain in the White Mountains and ending at little Hampton Beach, New Hampshire’s sliver of actual Atlantic Ocean coastline.

For those not clued in to this little race, teams are usually comprised of 12 people split between two support vans. The 200 miles is diced up into 36 legs. Runners in van one each take turns with the first six legs and then hands off to van two. Then repeat. Again and again until all 36 legs are done and you’ve spent 24-30 hours of your life either running or supporting other runners, and maybe catching an hour or three of sleep at most.

That means, with 434 teams, about 4,000-5,000 runners using 800 support vans on a mass migration across the state of New Hampshire at the speed of foot. Sounds like fun, right?

Hello Kitty. Athletic Club. Really.

And I should probably mention that one of the 434 teams is the Hello Kitty Athletic Club, who show up with pink bathrobes, Girl Scout sashes, and Hello Kitty hats? One carries a pink parasol. Then they will humiliate you by beating you. And everyone else. And run the 200 miles at a pace of 5:53/mile as they did this year.Here’s a video of them talking smack a couple of years back. This will not be my team, ever, but let’s face it, you wouldn’t want to miss this, would you?

Because this is a law blog, I’ll try to tie this weekend’s adventure into that subject. But let’s face it, sometimes a guy just has hunt down adventure for the hell of it. (When I wrote about running the Boston Marathon two years ago, I didn’t even try for a legal tie-in.)

Since I’m also the Race Director for the Paine to Pain Trail Half Marathon (October 2nd this year), I have other concerns about runners getting hurt (and the potential for liability). Because I don’t care to be sued. So this lets me riff on three activities near and dear to me: Running, race organizing, and the law.

So let’s take a look at the adventure, and the two big risks that come with it. This is important, I think, because of the public perception that people can sue for anything. While they might be able to sue, that doesn’t mean they can sue with success.

First is the obvious; the running surface. Running on streets presents a challenge for even the best of runners, as one twig or pencil could cause a rolled foot and send someone sprawling. Pot holes. Gravel. Uneven roadbeds. Road kill. Now run that surface on unlit roads at night while you’re exhausted with cars whizzing by on rural roads. You don’t really need a light to get the picture.

The second risk is the vehicles. Run on the road’s shoulder, as we did for mile after mile, and you must contend with cars and trucks. And drunks. And sleepy drivers driving support vans in your own race on oft-times narrow roads. Some intersections you cross on your own. Some have police or volunteers.

Those are the big two risks in running for which liability could conceivably be imposed on others for a runner’s injury.

Now I’m going to focus on New York law, since that is where I’m admitted, but the basic concepts are likely to be the same elsewhere, even if there might be deviations in some of the details.

This is the basic principle:

“[B]y engaging in a sport or recreation activity, a participant consents to those commonly appreciated risks which are inherent in and arise out of the nature of the sport generally and flow from such participation.”

Now let’s look at a sample case:

In Conning v. Dietrich a triathlete fell off a bike during a training ride organized by a club, and was then hit by a car. The accident happened when the plaintiff was following a fellow cyclist and the shoulder narrowed, and there was a difference in elevation between the shoulder and the gravel area to the right of the shoulder. When the plaintiff saw another cyclist leave the shoulder and swerve onto the gravel surface, she followed. Then attempted to get her bicycle back onto the shoulder, at which point the front wheel of her bicycle caught the slight rise in the shoulder’s elevation, and she fell into the roadway where she was hit.

In Conning, the plaintiff claimed against the club was negligent in allowing her to ride on “a decrepit and narrow path.” And she sued the driver of the car for negligence. Different defendants, same results?

No. There were different results when the defendants asked for judgment before a trial had even occurred. If there are no factual issues, and the law is clearly on one side, a judge can take the case away from a jury on a motion for summary judgment.

So as to the claims against the club, the club can fairly claim that the plaintiff assumed the risk of the ride. First off, “[t]he risk of striking a hole and falling is an inherent risk of riding a bicycle on most outdoor surfaces.” In addition, “the risk of encountering ruts and bumps while riding a bicycle over a rough roadway … is so obvious … or should be to an experienced bicyclist … that, as a matter of law, plaintiff assumed any risk inherent in the activity.” The same would no doubt hold true for runners.

If you read the opinion, you can also see subtleties in how the court treats actual competition compared to non-competition (a training ride) and the effects of written waivers. Yeah, we lawyers do know how to complicate things, but the decision is instructive for people on how a court goes about tossing out a claim. Essentially, the claim is tossed out because the club did not take the plaintiff on “an unreasonably dangerous roadway surface,” and that she was “able to observe the roadway as she was riding on the shoulder. Also, despite observing the narrowing of the shoulder, she continued to ride. Plaintiff, did not, as she knew she could have, slowed down or stopped.” She assumed the risk of her participation.

By contrast, the court ruled that the claim against the driver had issues of fact for a jury to resolve as to whether he “used that level of ordinary care that a reasonably prudent person would have used under the same circumstances and if not, whether the subject accident was foreseeable.”

So those injured in a competition that take place on a roadway would likely find differing results depending on who they believe was at fault. Want to blame the organizers of the event? That will be tough to do if the risks were forseeable. Want to blame that drunk driver who clipped you while you ran on the shoulder? Well, the risks of road racing do not include drunks veering off the road.

I taped my calf for the third leg of the race.

One other risk: That of self-inflicted injury because you refused to stop despite being hurt. In this race, I managed to injure my hamstring in the first leg of the event, and then managed to injure my calf in the second leg due to a change in gait while I nursed the hammy. Could I have quit in order to save myself from further injury? The problem is that this is a team event and, last I checked, there is no “I” in team. So I taped up the hammy with first aid tape, and then taped the calf. Then put on the running tights to hold it all in place. And when I thought the calf needed even more support, I found some red duct tape to hold it together for the third leg.

So I got injured. And I blame myself.

We ran two teams this year: Fox Chase 1 and Fox Chase 2. We finished 47th and 50th, with an average pace of 7:30. I’m seated, second from right.

Elsewhere on the race (I’ll put up more links if I find good ones):

Reaching the Beach (Run It)

Scenes from HKAC Victory at RTB 2011 (Hello Kitty AC)

Reach the Beach (RACE acidotic)

You guys know how much I love legalese, right?

You guys know how much I love legalese, right?