On Friday a construction crane collapsed in Manhattan that was dramatically caught on video, killing one and injuring others. And within hours, a law firm was boasting that it had a lawyer “on scene.” I shit you not. [Uh oh, someone is gonna get filleted and fricasseed, I can smell it coming!] From a legal perspective, it was quite the interesting show the firm put on.

On Friday a construction crane collapsed in Manhattan that was dramatically caught on video, killing one and injuring others. And within hours, a law firm was boasting that it had a lawyer “on scene.” I shit you not. [Uh oh, someone is gonna get filleted and fricasseed, I can smell it coming!] From a legal perspective, it was quite the interesting show the firm put on.

Now if I don’t write about such a naked case of ambulance chasing here, who will?

…Entering, stage right, the Fisher Injury Lawyers [golf clap] apparently based in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and led by Bryan and Tommy Fisher. [Cool! Will this be our latest contestant on How To Embarrass The Legal Profession?]

This four-lawyer firm also claims offices in Texas and New York. The New York firm is staffed by a puppy lawyer admitted to practice in 2014. [Huzzah, huzzah!]

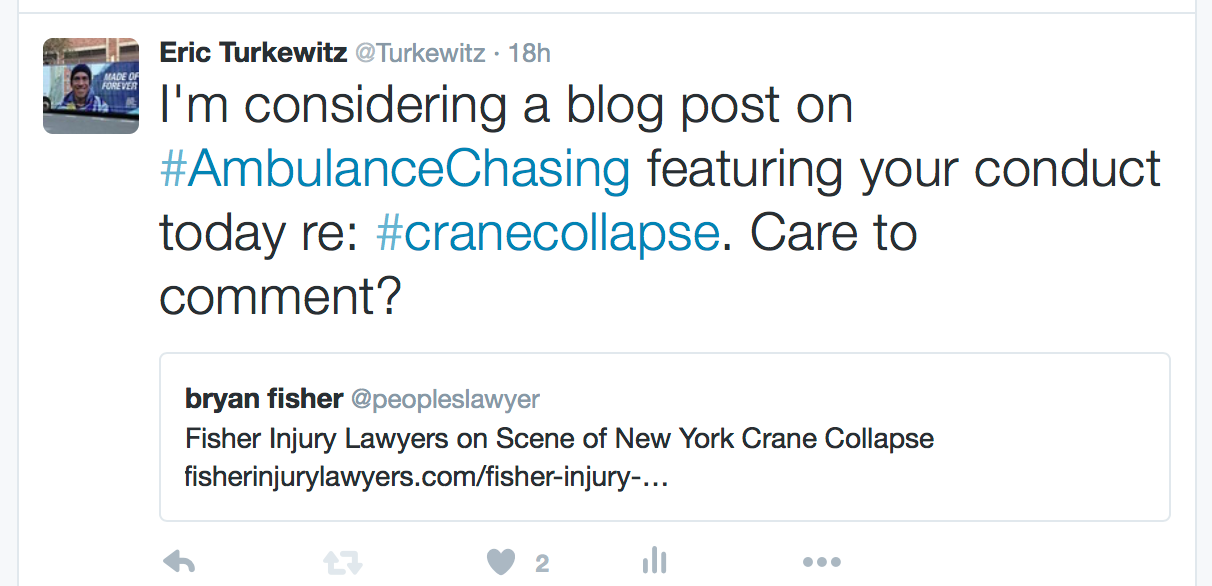

And awaaaay we go….Breaking on Twitter:

Fisher Injury Lawyers on Scene of New York Crane Collapse.

[Lawyers on the scene! No way! Often the actual chasers are “investigators,” so the chuckleheads can try to cover their tracks! These guys are awesome! No subterfuge!]

And not just Twitter. Oh no. Not in the age of social media. Also on Facebook. And their website. And LinkedIn. The Fishers seem to have covered all the bases.

And not just Twitter. Oh no. Not in the age of social media. Also on Facebook. And their website. And LinkedIn. The Fishers seem to have covered all the bases.

Except, of course, for that one little base that deals with New York’s anti-solicitation rules, which the Fisher Injury Lawyers of Louisiana seem to violate. [Oh no! I bet they didn’t see that coming!]

You would think that if lawyers were going to open a New York office and put a young attorney in there they would at least be familiar with our rules of professional responsibility on advertising and solicitation, right? [Hey, wait, I’m noticing a bit of snark here!]

These rules are, essentially, the very definition of ambulance chasing, a subject that I’ve written about many times before. [I wonder if the Fishers have ever read any of those pieces? I kid!]

A short review if you are reading this blog for the first time :

New York has a 30-day anti-solicitation rule in our Rules of Professional Conduct. It goes like this:

Rule 4.5(a) In the event of a specific incident involving potential claims for personal injury or wrongful death, no unsolicited communication shall be made to an individual injured in the incident or to a family member or legal representative of such an individual, by a lawyer or law firm, or by any associate, agent, employee or other representative of a lawyer or law firm representing actual or potential defendants or entities that may defend and/or indemnify said defendants, before the 30th day after the date of the incident…

[Hey! Maybe they thought it was a 30-second anti-solicitation rule? Simple misunderstanding! Could happen to anyone!]

When I wrote about this in December 2, 2013, it was Proner and Proner that was running ads after a train derailment in the Bronx.

And at the risk of repeating myself [Take the risk! Take the risk!], soliciting by sending a lawyer to the scene and with targeted ads on a website, Twitter, Facebook and LinkedIn, seems to me to fall pretty damn squarely within the meaning of the Rules to be solicitation as this is not generic advertising but targeted to a specific group of involved people.

And at the risk of repeating myself [Take the risk! Take the risk!], soliciting by sending a lawyer to the scene and with targeted ads on a website, Twitter, Facebook and LinkedIn, seems to me to fall pretty damn squarely within the meaning of the Rules to be solicitation as this is not generic advertising but targeted to a specific group of involved people.

[Oh no, this is getting ugly, these guys are going to win a prize for sure! I hope, for their sake, there isn’t another legal cite!] So here is the cite for the definition of solicitation:

Rule 7.3(b) For purposes of this Rule, “solicitation” means any advertisement initiated by or on behalf of a lawyer or law firm that is directed to, or targeted at, a specific recipient or group of recipients, or their family members or legal representatives, the primary purpose of which is the retention of the lawyer or law firm, and a significant motive for which is pecuniary gain…

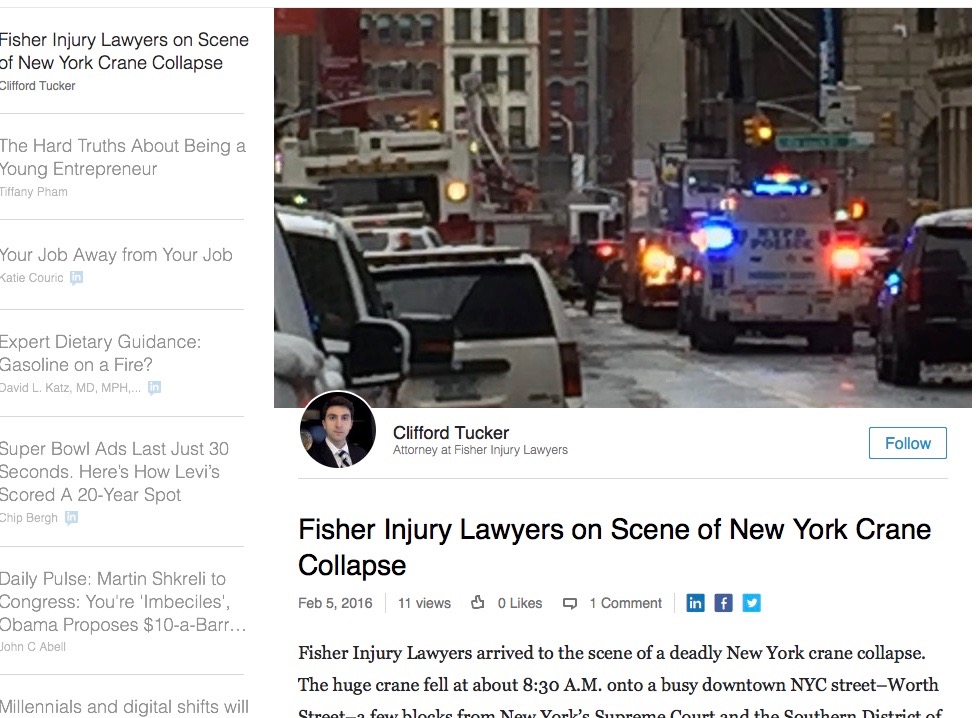

The initials of the young lawyer who apparently went to the scene are C. T., but because he’s so young and I presume doing the bidding of his boss, I elected not to use his name. [I can see it in the graphic! I can see it in the graphic!] Admittedly that’s a close call, since he should know better anyway. It’s a good example, though, of a lawyer that must learn how to say no. [You didn’t name him in a Google-friendly way?! You’re getting soft!]

The initials of the young lawyer who apparently went to the scene are C. T., but because he’s so young and I presume doing the bidding of his boss, I elected not to use his name. [I can see it in the graphic! I can see it in the graphic!] Admittedly that’s a close call, since he should know better anyway. It’s a good example, though, of a lawyer that must learn how to say no. [You didn’t name him in a Google-friendly way?! You’re getting soft!]

It’s also worth noting that out-of-state lawyers are bound by our code of professional responsibility (Rule 7.3(i)):

(i) The provisions of this Rule shall apply to a lawyer or members of a law firm not admitted to practice in this State who shall solicit retention by residents of this State.

[Is this the part where Bryan Fisher says, “Oh shit!!!”? I’m sure he won something for this escapade!]

Now what would happen if Fisher Injury Lawyers should somehow procure a client by this chasing (and then, perhaps, flip the case to local counsel in exchange for ⅓ of the fee)? The answer, I think, is that a judge could/should take a close look at those Rules, and assuming that judge agrees with me, take away any legal fee as one can not profit by violating the Rules. [Oh man, if that happens he’s gonna need a tushy doctor to repair the new hole!]

As for any local counsel that should be contacted about a referral (in any case), one of the questions we should always ask is, “How did you get the client?” There are no doubt many that would turn a blind eye to the original source, but the source of clients is a recurring problem not only with newfound referring attorneys, but with the hordes of “find a lawyer” sites that may be using unethical black hat techniques to procure “leads.” [You mean one of them might one day need a tushy doctor too?]

It’s a good time to remember that ethics and marketing are in a deep embrace. Lawyers must be careful who they climb into bed with, because outsourcing your ethics is a communicable disease — whatever vice your agent commits for the business falls to you also. Such is the nature of agency.

Does anyone want to be the test case in the Appellate Division for lawyers outsourcing their marketing (and ethics and reputation) to others? [Hands? Hands? Can I see a show of hands?]

It’s also worth noting that any firm with even a basic knowledge of New York practice would also know that you can’t use a trade name like “Injury Lawyers” (Rule 7.5(b)).

But really, the core of this is ambulance chasing. [Ya’ think?] I bring up the other issues only in the context of some lawyers believing it’s OK to just waltz into other jurisdictions without really having a clue as to how they actually operate.

I contacted Bryan Fisher for comment on Friday, the day he published his advertisements — using Twitter since that is one of the social media platforms he elected to use [Nice touch!] — and he has not yet responded:

And so, into the Personal Injury Hall of Shame I hereby induct the Fisher Injury Lawyers, based primarily in Baton Rouge, Louisiana,[Winner! Winner! We have a winner!!!] for its sterling effort to drag the legal profession down into the muck. And having the public (jurors) think even worse of us and our clients than they already do. [Aha! So that’s why you’re writing about them!]

And if they happen to be reading this [Oy vey! Are they gonna be pissed at themselves for having done this!], you guys have four things to hope for:

- Everyone is talking about the Super Bowl and doesn’t give a damn about this;

- New York’s disciplinary committees simply don’t care about enforcing the 30-day anti-solicitation Rules, and are more interested in Lady Gaga botching the lyrics of the National Anthem by swapping out “gallantly streaming” for “valiantly streaming;”

- This blog was so poorly written due to all the Greek Chorus nonsense, that no one took its underlying message seriously [Hey! You wanna complain, blame the casting director!]; or

- This blog is so poorly read by others that the issue never comes to their attention.

(hat tips to Gerry Oginiski and Samson Freundlich)

Dear presidential debate moderators:

Dear presidential debate moderators: