Lawyers are in the persuasion business. Whether we are trial lawyers standing before juries, appellate lawyers, commercial lawyers negotiating a deal, or pretty much anything else.

Advocating is kinda what we do. Marshal the facts and apply it to the law and say, “See? This is why you should do…” Finding the exact right facts and the exact right law — and, of course, the exact right audience — is part of the secret sauce of success.

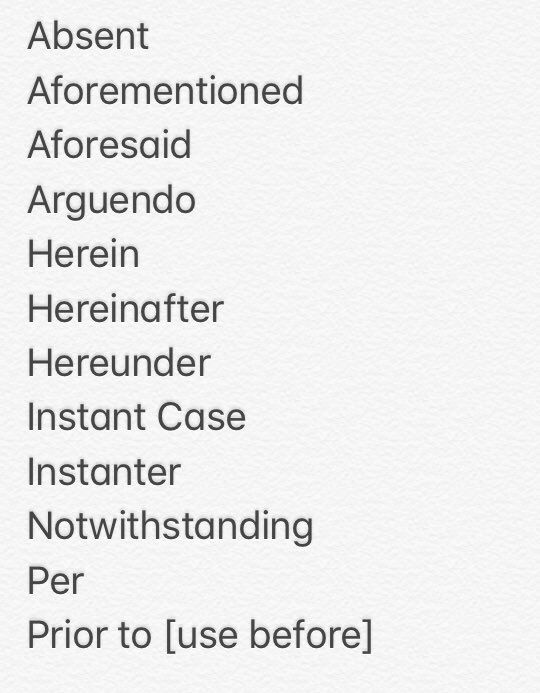

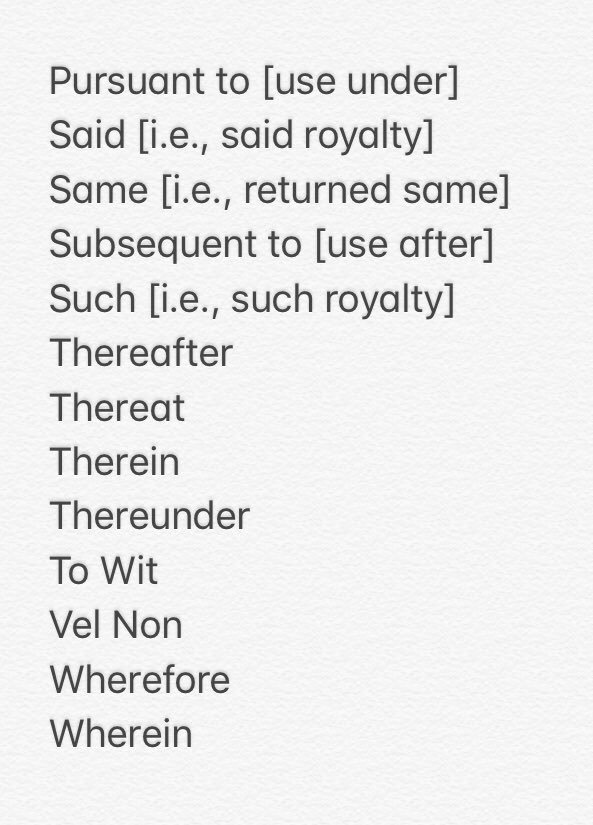

And then there are persuasion failures. Ad hominem attacks, for example, merely expose a person as bereft of competent argument. Purely emotional arguments by the unduly passionate are, of course, a classic. So is shooting the messenger. And only fools would deliberately try to piss off the people or groups they were trying to persuade, or make the arguments in the wrong place.

These dos/don’ts are second nature for most of us, and it leaves many lawyers just shaking their heads when we hear people bringing on the stupid as they violate what we see as simple rules, be it at a cocktail conversation or on Twitter.

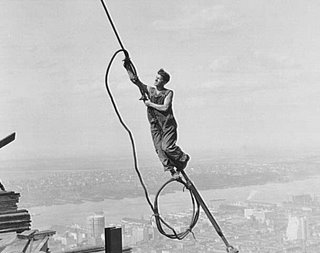

With that in mind, I bring to you a colossal failure in persuasive argument that I witnessed while trying to get to my office Friday in Manhattan. It was a demonstration where roughly 100 college students thought it would be a keen idea to stop all traffic on Third Avenue in Manhattan between 44th and 45th streets, stretching hand to hand both across sidewalks and street to obstruct pedestrians and cars.

For those unfamiliar with the area, this is a broad and heavily travelled avenue running uptown just after traffic empties out of the Queens-Midtown Tunnel into the heart of midtown Manhattan. So a blockage just upstream of this point will seriously back traffic up, both on the avenue and the side streets, and quickly affect many thousands of people.

Which tends to piss people off. Making matters worse was that no one in the protesting group, calling itself IfNotNow, thought to even hand out literature to folks who were walking by, or stuck in their cars, so they would know what the hell the protestors claimed to be so pissed about.

But they did wear shirts and hold signs with a stylized Star of David on them and slogans that said something about Birthright Israel.

So the only thing folks would know was that a bunch of Jews were obstructing their daily commute. That is the only thing they would know.

Now the vast majority of Jews know what Birthright Israel is — a free 10-day trip to Israel for Jews between 18-26, designed to strengthen Jewish identity. It’s a 501(c)(3) charitable organization. Over 500,000 young Jews have taken this free trip. And it’s deliberately apolitical.

But most non-Jews haven’t a clue as what this charitable foundation is. And those stuck in traffic who could see what was going on knew only that a bunch of Jewish students were stopping them from doing what they had come to Manhattan to do.

In other words, the organizers had not only violated one of the first rules of persuasion but may have added to the climate of anti-semitism by pissing all over people that just wanted to get to work. (They were damn lucky, I might add, for the benevolence of New Yorkers, for anyone in a hurry that was in the front line of cars that morning could have just let their car slowly roll toward the arms outstretched across the avenue and slowly pushed them away — a recipe for disaster since the cops hadn’t arrived.)

Pedestrians, to get to where they were going, were forced to take a long walk around by going over to Second Avenue or Lexington, or as some did, wrench apart the clasped hands of youth and physically push their way through. Which some did. Because New Yorkers.

Their argument, to the extent you can even call it that, and which I could only find out later because they didn’t bother to have any literature for those who might be interested, was that they wanted this massive private charitable organization to focus on the politics of the almost-100-year-old conflict with Palestinians. The protest location was picked because the office of Birthright Israel was located there. In addition to blocking the building entrance, they elected to also tie up the east side of midtown.

Birthright Israel, of course, doesn’t set Israeli policy. It isn’t the government, or even a political party. The protest was very much yelling and screaming at the wrong people.

The NYPD arrested 15 of the protestors for disorderly conduct after repeated warnings to leave.

Birthright Israel, in turn, put out a statement telling the protestors to go shit in a hat and pull it down over their ears:

“We do not respond to threats and demands from political activists leveraging our long-standing good reputation in order to advance their agendas.”

So, in sum, the protestors managed to do the worst thing that they could do — they pissed off non-involved people potentially making anti-semitism worse, and did so while aiming at the wrong target.

And that is how not to persuade people to your issue, whatever your issue might be.