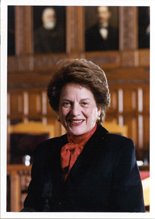

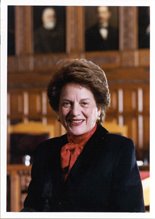

New York’s Chief Judge, Judith Kaye, has hit the mandatory retirement age of 70. She gave her farewell speech yesterday, according to this story in today’s New York Times.

New York’s Chief Judge, Judith Kaye, has hit the mandatory retirement age of 70. She gave her farewell speech yesterday, according to this story in today’s New York Times.

Elevated in 1993 under Gov. Mario Cuomo, she was not only the first woman to hold the top spot, but also served longer than any other chief. She had been an associate judge for 10 years before that, giving her 25 years up on Albany’s Eagle Street where the courthouse sits.

She has opined on everything from jury selection to court consolidation to judicial salaries, in which she is the lead plaintiff in a landmark suit against the executive and legislative branches to force higher pay. And on that last subject, she held forth again during her remarks. According to the Times:

She also restated the case for a pay raise for judges, even in tough fiscal times. She said in her speech that she did not want to talk about the lawsuit she filed in April to force lawmakers to increase judges’ salaries. But she said it was “heartbreaking and frustrating and demoralizing beyond description” that “our proud judiciary” — some 200,000 full-time employees, including judges — had been the only part of state government to be denied “the increases they seek.”

Her lasting legacy might be (based on the fact that the Times led with this) that judicial salary lawsuit. The Times elected to lede with this:

After delivering what she called her “swan song,” an hourlong speech on Wednesday in which she said her role as “chief plaintiff” in a lawsuit over judicial pay “sickens me,” the state’s chief judge said she had not endorsed anyone as her successor.

Judge Kaye — and this probably comes as no surprise from a blog that (tries) to focus on New York law — has been the subject of more posts here than any other individual. Since I only started two years ago, my posts on here deal primarily with her flip-flopping decision on whether she should, or should not, try to gain those long-needed judicial pay raises by suing the other branches of government.

This is a wrap-up of my posts on Judge Kaye:

- Spitzer Moves To Restructure Courts With Chief Judge Kaye’s Plans (1/4/07)

…she described the frustrations involved with fixing New York’s archaic court structure, and the decades long struggle to do so…

- Where Are Our Judicial Pay Raises? (1/29/07)

New York’s Chief Judge Judith Kaye is again speaking out on the appalling situation where our judges must go “hat in hand” to the legislature to get paid a decent wage. This comes fresh on the heels of Simpson Thacher’s decision to give rookie associates $160,000 plus a $30,000 bonus, a decision followed by other firms.

- New York Trial Justices Oppose Role In Chief Judge’s New Screening Committees (2/12/07)

New judicial selection rules in New York faced a new problem today when the New York Law Journal reported on its front page that trial justices are opposed to their being part of new screening committees, being set up by Chief Judge Judith Kaye.

- New York’s Chief Judge Threatens To Sue For Pay Raises (4/9/07)

With badly needed judicial pay raises being left out of New York’s April 1st budget agreement, New York Chief Judge Judith Kaye threatened to bring suit against the legislative and executive branches for the raises. In harsh and emotional language she held a press conference and put out a statement on the issue.

- A Judicial Brawl in New York As Chief Judge Kaye Abandons Lawsuit Threat (7/9/07)

New York’s Chief Judge Judith Kaye has abandoned her previous threat of a lawsuit against the legislative and executive branches for the failure to grant even a cost-of-living pay raise over the last nine years…….Justice Goodman, using an extraordinarily sharp tone considering her target, and often dripping with sarcasm that attorneys are unaccustomed to hearing from the bench, is anything but kind to Chief Judge Kaye…

- New York Chief Judge Flip-Flops On Lawsuit. Again (12/11/07)

What, exactly, is the rest of the state’s judiciary to think?

- New York’s Chief Judge Kaye Finally Brings Suit for Judicial Pay Raises (4/10/08)

A year ago last April New York’s Chief Judge Judith Kaye threatened to bring a lawsuit because the judiciary hadn’t had a raise, even for the cost of living, for eight years. Their salaries remained stuck at $136K while first year associates at BigLaw top out over $200K including their bonuses.

Then in July she reversed herself, setting off a furious brawl among the judiciary when she said she would not bring the suit.

Then in December our Chief Judge Hamlet flip-flopped again and said she would bring suit.

- Wachtell and Judicial Ethical Violations in New York’s Judicial Pay Raise Suit? (4/10/08)

Yesterday Chief Judge Judith Kaye brought a lawsuit for long sought judicial pay raises on behalf of the New York judiciary. In doing so, some ethical issues now present themselves based on the free legal services offered to the judiciary by Wachtell Lipton, an issue quite apart from the more obvious question of how any judge that is part of the plaintiff’s class can actually hear the case.

- Did New York’s Chief Judge Sue State in the Wrong Court? (4/11/08)

Yesterday Chief Judge Judith Kaye sued the State of New York (among other defendants) in Supreme Court, the state’s trial level court. But New York law provides that the Court of Claims has exclusive jurisdiction of suits against the state for money damages. Did New York’s Chief Judge sue in the wrong court?

- Kaye v. Silver, Judicial Pay Raise Suit (Today’s Argument) (7/17/08)

I just came back from the courtroom where the matter of Judith Kaye (NYS Chief Judge) against Sheldon Silver (Speaker of Assembly) is being argued. This is the judicial pay raise suit that is, perhaps, the most unique suit ever filed in the state.