Professor Franks, via LinkedIn

Monday someone blocked me on Twitter. It’s the first time that has happened to me since I started sporadically using the service in 2009.

Me? Blocked? What malicious and impertinent crime had I committed?

Apparently, I committed the vulgar, discourteous and insulting crime of asking a law professor for a citation, and then discussing it. I kid you not.

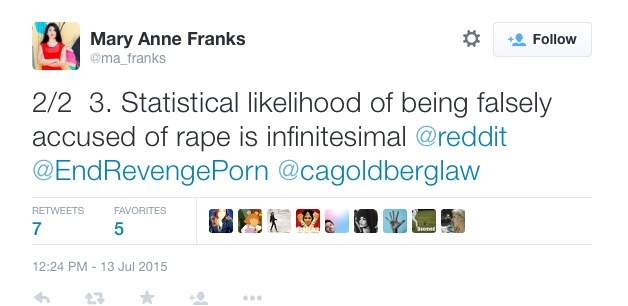

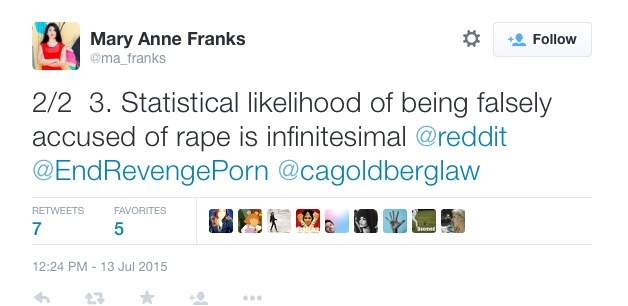

As I skimmed my Twitter feed upon return back from a delightful vacation, I saw this curious tweet from Professor Mary Anne Franks about the de minimis likelihood of a rape allegation being false:

Now I’m no student of rape statistics or studies for sure — it isn’t what I do, and it isn’t one of the issues I’ve routinely tackled in the 1,300+ pieces I’ve written here since 2006.

Now I’m no student of rape statistics or studies for sure — it isn’t what I do, and it isn’t one of the issues I’ve routinely tackled in the 1,300+ pieces I’ve written here since 2006.

But I was curious about the comment, certainly, since it carried a presumption of guilt, which is deeply at odds with our jurisprudence. And it was also at odds with stories in the popular press about rape accusations that turned out to be either questionable or outright false.

This includes such front page stories as the Duke Lacrosse players scandal, the poorly sourced Rolling Stone article from the University of Virginia for which it apologized (A Rape on Campus), Columbia University student Emma Sulkowicz who carried a mattress around campus after claiming she was raped, and the Central Park Jogger case. And, of course, there is the infamous case of the Scottsboro Boys.

But you know what the problem is with all those reports? They are not empirical evidence. While they discuss the facts of those particular cases, this means nothing for the big picture as to whether the incidence of false rape accusations is “infinitesimal,” or common, or somewhere in the vast gray area between.

While I don’t do criminal defense work, I do try civil cases, and I am aware of how stories in the popular press help to shape societal opinions (and, therefore, the jury pool). A classic example from my field is the McDonalds hot coffee case. I can’t remember the last time I picked a jury without discussing it.

The problem is that such stories are, by definition, outliers. If they weren’t outliers, they wouldn’t be on the front page where they then go on to shape public opinion.

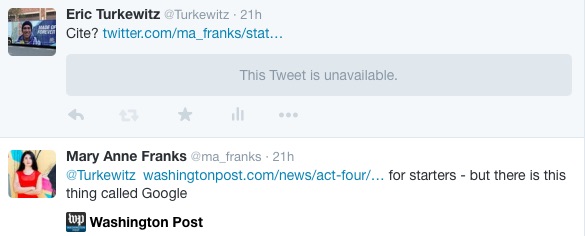

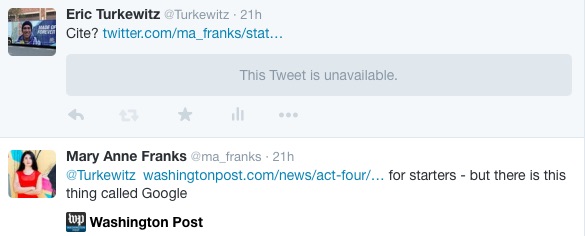

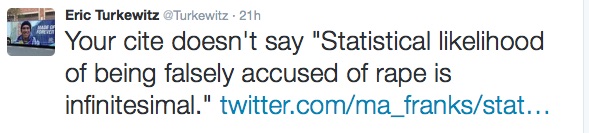

Wanting to know the source of Professor Franks’ conclusion, I inquired with a very simple and benign citation request regarding her claim that false accusations of rape were “infinitesimal.” And with that she directed me to a Washington Post article that cited a variety of statistics, from different studies:

While I won’t summarize the entire article — since as you will see in a moment that is not the point of this post, and you can read it if you want — the author wrote about one significant study stating that there is “a profound disagreement on what counts as a false allegation.”

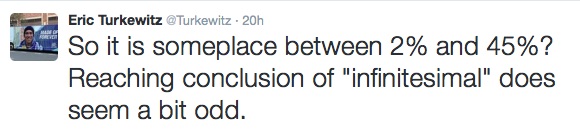

Due to the problem of shifting definitions (as well as unreported rapes), you can see by the article that it’s difficult to get a real handle on the extent of the problem. In fact, the very story that Professor Franks cited to me had studies showing false rape accusations varying between a low of 2% to a high of 45%.

The only thing that seemed to be clear about the statistics is that nothing was clear.

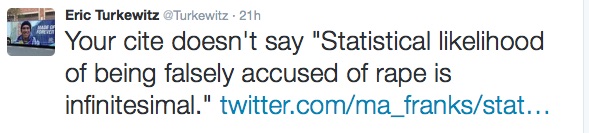

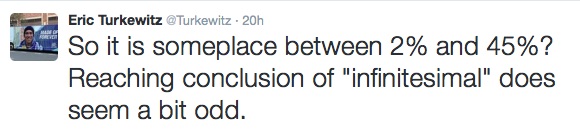

So I noted to Professor Franks that not only wasn’t the word “infinitesimal” part of the story, but that the very citation she gave me seemed to demonstrate otherwise:

And she blocked me. For challenging the conclusion she reached from her very own citation. This is academia?

Now where I come from, a lawyer doesn’t make an assertion that can’t be backed up with proof. Evidence is the heart and soul of any case or argument. I get challenged on my proof all the time, and I challenge defendants on theirs. Over the course of the 30 years since I was graduated from law school, I’ve become pretty confident that this is the way the system works.

The challenging of proof is what, hopefully, assists the finders of fact (be they juries or judges) to become the proverbial fly on the wall that determines what “actually happened” when one bit of evidence contradicts another.

It’s therefore routine in trials for each side to look at the opening statements of the other, and try to find some fact that they claim wasn’t proved at trial, and then pound away at this, calling it an exaggeration or falsity in an attempt to tarnish the entire case of the other side.

And that is why lawyers speak carefully in making assertions of fact, for otherwise we tarnish not only ourselves, but worse, our clients or causes.

I can’t help but wonder: What happens if a legal adversary challenges an assertion that Professor Franks makes in a motion or appeal? What happens if a judge challenges her cite? Will she stand in the well of the courtroom and try to block the judge?

And what happens when a student challenges a citation that Professor Franks gives in class? Does she block the student? Will she cover her ears and sing?

What kind of lesson does she teach her students by saying that, if a person challenges your citation, you just block them?

This post isn’t about rape. It’s about evidence. And teaching. And lawyering.

I’m reminded by this episode of an experience I had as a newbie blogger, with just months under my belt. Walter Olson at Overlawyered had written something and I posted an opposing view. So what did Olson do? He amended his post to read, And for another view, see Turkewitz. With a link.

This was the exact opposite of blocking. And it brought home to me in a heartbeat what the whole blogging thing was about. It’s about an exchange of ideas, some of which may be critical. Olson and I may butt heads on issues from time to time, but I’m indebted to him for that lesson.

And it was the subject of a post I wrote a few years ago celebrating that very fact (Twittering With the Enemy– A Blogospheric Celebration). Professor Franks would do well to take note.

A last thought. When I was a kid, I remember one of my teachers telling me that the best students were the ones that challenged their teachers with questions. This was the pool of students, he told us, from which he hoped would one day emerge a son-in-law.

Good teachers are happy when students’ minds are buzzing with inquisitiveness. Good teachers aren’t afraid of the questions. Or the answers. Or of learning something new.

Update (7.16.15) – In exceptionally stark contrast to Professor Franks, 9th Circuit Judge Alex Kozinski had this to say in an article that deals with his ideas (in part) on how to change the jury system:

If my proposals raise controversy and opposition, leading to a spirited debate, I will have achieved my purpose.

Now ain’t that refreshing?

———

Elsewhere, some on point, some tangential:

Professor Franks and the False Dichotomy (Jay Wolman @ Legal Satyricon, who was also blocked)

The ITIF’s Confusion on Free Speech and Revenge Porn (Scott Greenfield @ Simple Justice)

Professor Twitter and the Problem of the Low False Rape Narrative (Francis Walker @ Data Gone Wild)