Brooklyn’s county courthouse, 2008. Photo credit: me.

Two recent articles in Reason by its Editor in Chief, Matt Welch, raised issues about New York’s jury selection process and are very much worth discussing. Welch, as you’ll see, didn’t find the experience as amusing as my screenwriter-brother, or get any of the hoped-for excitement that my niece Ellen wanted, and certainly didn’t appreciate it the way I did when I sat jury duty many moons ago (and was selected).

So on to the main event: Welch. When I first read the first of his two articles in his libertarian oriented magazine, I was ready to mock, parody and lampoon his never-ending stream of whines, complaints, grumbles and gripes. That was my gut reaction, and it was going to be fun.

But there was one big point he made and one big point that he botched, and both are deserving of attention.

First, his take on the selection process: He bitched, whined, moaned and complained about the Brooklyn courthouse architecture, the dirty plaza in front, the security, and the ever-so-slow orientation and waiting to be placed in a voir dire pool to be questioned by lawyers. (How Jury Duty Almost Turned Me into an Anarchist)

When he finally gets there, he sounds like Arlo Guthrie showing up to his draft board after a long night of drinking — prepared to be injected, inspected, detected, infected, neglected and selected. In meeting the lawyers for the case, what type of mind set do you think he started with?

Is this stuff important, or just superficial belly-aching by someone looking for material to write about, as he did in his book about similar issues?

Answer: It’s important!! You don’t shoot the messenger because you don’t like the message. He made a valid point that some jurors may be poisoned by the process itself, even before actual selection started. Anyone who practices law in Brooklyn knows we need vastly more room and judges.

And court administrators should take note, to the extent that they have the capacity to actually do anything about it within the tight financial constraints that the Legislature imposes.

Subway art, Borough Hall station where the courthouses are. Photo credit: Me.

Wouldn’t everyone — jurors, lawyers, judges, clerks and officers — rather be inside that great, big, new, shiny federal courthouse down the block? You betcha. It’s vastly more civilized, and jurors don’t start the trial phase, if they get there, feeling abused. The building itself, and the federal administration of it, oozes competence and justice (much to the chagrin, likely, of criminal defendants).

And feeling abused is important, for then the aggravations and irritations of the process itself may simply confirm pre-existing biases to the detriment of one side or the other.

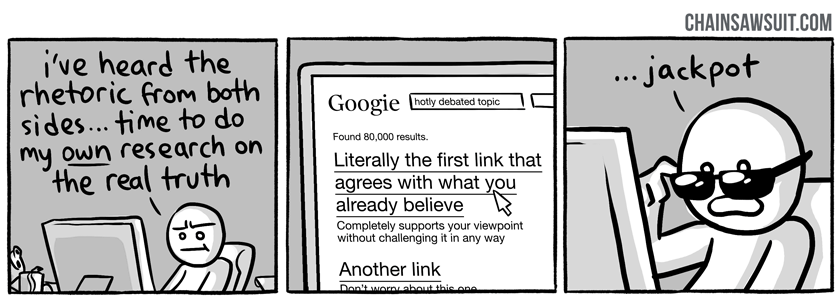

Confirmation bias is a huge issue to deal with in jury selection (and the issue Welch botched). Because many people instinctively look for facts to “prove” the thoughts they had before hearing evidence, or reading a news story. They want to know that their opinions were “right.” This is most commonly seen in politics, where everything on “the other side” is wrong.

Welch states that he wants to do the right thing, claiming near the outset of his piece:

Jury duty is a chance to bond with fellow citizens you might not otherwise meet, peek under the hood of our flawed judicial system, and do our small part to advance the noble democratic ideal of participatory justice.

And he also writes, in his own defense that:

…I would also say that within libertarianism there’s a broad appreciation that the civil system provides the kind of redress unavailable in places like Western Europe, for example. And at any rate, I don’t have strongly held opinions about it; my strongly held opinions are about the criminal justice system.

But when I look under the hood of his writings, in just these two pieces, I see a pre-existing proclivity, and the concern any lawyer would have for potential confirmation bias if he were to sit in judgment. Describing the case as he first hears about it in the jury selection room, he writes:

It is, to my chagrin, a civil trial, not a criminal one, involving the category of incident one might see advertised in a subway car.

Ouch. OK, he is entitled to his opinion for sure, regardless of whether I like it or not. But it’s hard to miss the underlying bias.

In his second piece, entitled How Lawyers Pre-Try Cases During Jury Selection, he tries to claim the voir dire process (and the jurors) are abused by the lawyers trying their cases in the room without a judge or evidence.

And he continues his complaints by dropping another clue as to his underlying feelings, calling plaintiff’s counsel a “Court Street Lawyer” with a link to a derisive description.

Moses with the law, at the entrance to the Brooklyn courthouse. 2008. Photo credit, me.

Now the vast majority of people will say, and likely believe, that they can sit fairly and listen to evidence, if the question is put to them directly. But this is a very superficial question, and ignores the underlying biases a juror may have. And that, in turns ignores the very legitimate concerns that such jurors will engage in confirmation bias as they listen to the evidence. This is what the trial lawyer needs to worry about, regardless of who they represent.

Welch himself knows about confirmation bias. On just the 4th page of his book The Declaration of Independents, he writes with co-author Nick Gillespie:

You may have heard of confirmation bias, whereby people tend to notice and believe whatever rumors, news stories and quasi-academic studies confirm their world view.

But seeing it in others is altogether different than seeing it in the mirror.

It was during that second piece, that he argued that the lawyers were looking to get rid of all the potential jurors with expertise. But this is not what trial lawyers do. We look to get rid of those with deep-seated biases, because we worry that such people will simply look for evidence during a trial to confirm them.

One example of what Welch thinks is an attempt to argue the case in the jury selection room and condition the jurors is the common question trial lawyers ask when talking about money and damages, “If you thought the injuries were substantial would you hesitate to bring back a substantial verdict?” But I (and so many others) ask it because I want to know about a political bias — do they have any feelings about one-size-fits-all damage caps? I would consider that information to be pretty important. So would my adversary.

And the reverse is also true when discussing the issue of damages, and is also asked: If the plaintiff shows only minimal injuries would you have any problem bringing back a minimal verdict? I’ve yet to meet a defense lawyer that is a potted plant. (The wise plaintiff’s lawyer asks both questions – asking about both the substantial and the minimal.)

Another example of bias are potential jurors who work in the medical field, sitting in a medical malpractice case. Are these people automatically excused due to their expertise?

Some would be inappropriate due to subconscious concerns about what their co-workers would say if they brought back a plaintiff’s verdict. It’s the lawyers job to ask about that bluntly and make the juror ponder it.

Yet others might acknowledge that they have seen all manner of bad things happen in a hospital. So dumping medically educated jurors or keeping them could go either way.

And more important than the medical practitioner is the parent of one. For now emotion/bias is even more likely to be a factor as the lawyers fear this juror seeing their own kid as a defendant.

Thus, Matt Welch’s two Reason articles are useful: Useful in describing the oft-times miserable experience that some jurors have, so that court administrators and legislators that hold the purse strings can address them and so that lawyers can appreciate what these potential jurors have gone through before the first questions are even asked.

But it is also useful in ways Welch might not have appreciated, as a good example of seeking out the underlying biases that potential jurors might have, and addressing head-on the concerns about them engaging in confirmation bias as they listen to the evidence.

Addendum: As I re-read this piece this morning while sitting in that same courthouse, just after publishing, I remembered I had written back in 2008 about the highly scientific method that I use for jury selection: Who Sits Jury Duty? (The Turkewitz Beer Test)

I don’t even have to look at Twitter to know what is happening given the announcement that Bill Cosby has been charged with aggravated indecent assault based on a 2004 incident.

I don’t even have to look at Twitter to know what is happening given the announcement that Bill Cosby has been charged with aggravated indecent assault based on a 2004 incident.