Post deleted. Why? Because I said so.

September 24th, 2015

September 24th, 2015

September 21st, 2015

Two years ago I published a post after the summer about the fact that my blog had slowed down. Summers can do that, when many trial lawyers take vacations, as well as judges, parties and witnesses. Fewer trials, fewer depositions, slower life.

Two years ago I published a post after the summer about the fact that my blog had slowed down. Summers can do that, when many trial lawyers take vacations, as well as judges, parties and witnesses. Fewer trials, fewer depositions, slower life.

And at that time, I also noted that I would not come here and write stuff, just for the sake of writing.

I’ve been busy, very busy, and this blog will always take a back seat to family and work. It will continue to be down/slow for at least another month, with a family bar mitzvah coming up and the trail race that I organize likewise filling my non-lawyering time.

Family, fun, passions.

This note serves merely as an explanation for the quiet. All is good, by way of work and family. All is good.

And to those celebrating, I wish you a happy and healthy new year.

August 4th, 2015

In a ruling late last week, the attorneys for Douglas Kennedy, son of Robert F. Kennedy, were disqualified from defending him in a suit arising out of his alleged assault of two nurses.

The January 7, 2012, incident, widely covered in the media, arose when Kennedy attempted to take his three-day old son outside of Northern Westchester Hospital for fresh air. He was stopped by nurses who said he was not permitted to do so without a bassinet, and a tussle ensued which was partially caught on video.

Kennedy was acquitted of misdemeanor charges of child endangerment and harassment in the second degree, but a civil suit followed for personal injuries.

The remarkable disqualification came about due to a subject I have extensively covered on this blog, the way that defense medical exams are done and reported. (Many judges use the misnomer IME though the exams are not actually independent. Chief Judge Lippman agrees with me on this. These exams are commissioned by counsel, not the court.)

In this case, three doctors examined each of the nurse-plaintiffs, and four of the six reports said that the injuries were causally connected to Kennedy’s actions. So what did the defense lawyers do? They gave more materials to the experts to persuade them to change their conclusions. And on at least one occasion, met with the expert, along with Douglas Kennedy, to persuade him.

In other words, the defense took multiple bites at the apple. Instead of giving all of the information at the outset, they gave only some, and when the reports didn’t come back the way they liked, they gave more. And with one of the experts, went back to the well three times for amendments.

From the well-reasoned opinion of Judge William Giacomo with my bolding on the important stuff that the defense lawyers wanted changed:

During July of 2014, each plaintiff submitted to three IMEs performed by defendant’s insurance company. Plaintiff Anna Lane submitted to a psychological lME with Dr. Richard DeBenedetto, an orthopedic IME by Dr. David Elfenbein, and a neurological IME by Dr. Elliott Gross. Plaintiff Cari Lucania submitted to a psychological IME with Dr. Victoria L. Londin, an orthopedic IME by Dr. David Elfenbein, and a neurologicallME by Dr. Ronald Silverman. With respect to Anna Lane, in July 2014, Drs. DeBenedetto and Elfenbein each issued an IME report with a finding that her injuries were causally related to the January 7,2012 incident. Dr. Gross found no causal relationship. With respect to Cari Luciano, Drs. Londin and Elfenbein each issued an IME report with a finding that her injuries were causally related to the January 7, 2012 incident. Dr. Silverman found no causal relationship.

With those reports of causation in hand, defense counsel then went to work to get them changed:

Thereafter, in August of 2014, defense counsel sent Drs. DeBenedetto, Elfenbein, and Londin additional information with regard to plaintiffs (including plaintiffs’ deposition transcripts) and medical records (including the neurological IME reports which found no causal relationship) together with a copy of Judge Donohue’s November 20,2012 written decision in the criminal matter.

Why disqualification? Because these doctors are witnesses, and the lawyers that asked them to change their reports are now also. Plaintiff’s counsel wants to call them to show, no doubt, his opinion of chicanery in the defense of the case. And you can’t be both a witness and counsel in a case, as it violates our disciplinary rules.

From the court regarding the Dr. David Elfenbein, regarding the three separate addendums to his report:

On July 8, 2014, August 20, 2014, and October 10, 2014 Dr. Elfenbein issued addendums to his original July 2, 2014 report. The July 8, 2014 and August 20, 2014, addendums further indicated a causal relationship between Lane’s injuries and the incident. However, on October 10,2014, after attending a meeting, at Dr. Elfenbein’s office with defense counsel and defendant, Dr. Elfenbein issued a third addendum wherein he no longer found Lane’s injuries were causally related to the incident. In his October 10, 2014 addendum Dr. Elfenbein states “Attorney Douglas presented mewith medical records and did review some key aspects of them with me. He then asked me verbally and in writing to review those records in their entirety and readdress my conclusions regarding causation in my Independent Examination.”

Interestingly, the opinion by Judge Giacomo exposing this incident is likely to significantly impair Dr. Elfenbein’s ability to conduct these exams in the future. He is likely to be, shall we say, harshly criticized in future cross-examinations with a claim that he will bend to the hand that feeds him.

All the reports were subsequently changed to reflect that there was no causation for the injuries. Not just one report, but all. And that makes the lawyers who did this at, Douglas and Newman, important witnesses.

As per the court, in ordering disqualification:

In order to disqualify counsel, a party moving for disqualification must demonstrate that (1) the testimony of the opposing party’s counsel is necessary to his or her case, and (2) such testimony would be prejudicial to the opposing party (see S & S Hotel Ventures Ltd. Partnership v 777 S. H., 69 NY2d at 446; Daniel Gale Assoc., Inc. v George, 8 AD3d 608, 609 [2nd Dept 2004]).

Here, plaintiffs have established that the testimony of defense counsel Douglas & London, PC regarding its conduct and interactions with the IME doctors, including what occurred during the meeting with Dr. Elfenbein, to warrant a change in their original determination that plaintiffs’ injuries were causally related to the January 7,2012 incident is necessary to their case and would be prejudicial to defendant. (See McElduff v. McElduff, 101 A.D.3d 832, 954 N.Y.S.2d 891 [2nd Dept 2012]).

Let me be clear about something: This does not happen. In the world of personal injury litigation, this is exceptionally rare. In fact, I’ve never before heard of it happening.

But the decision is, in my opinion, correct. If a lawyer forwarded additional documents to one doctor, the result may well have been different. But three doctors? And meeting with one for the express purpose of getting that report changed for a third time? Yeah, that lawyer is now a witness. And that can’t be good for the defendant, Douglas Kennedy.

The court here effectively protected Kennedy from the conduct of his own counsel. It’s better for him to have them as non-party witnesses who will be skewered than to have them as his counsel in the well of the courtroom who will be skewered. The decision is here:Luciano and Lane v Kennedy

Hat tip: Eliott Taub

Updated: The New York Law Journal also has the story, on its front page, with interviews of the attorney and defense counsel’s defense of their conduct. They claimed, in part, that they didn’t have all the information:

“It was plaintiffs that withheld information, downplayed information and the doctors didn’t have it…”

The problem with that is that, as Judge Giacomo writes, some of the information furnished to the doctors apparently pre-existed. This includes the plaintiff’s deposition (usually available) and the court opinion in the criminal matter.

Also, a second decision exists from Judge Joan Lefkowitz, dated July 2nd, where she deals (via Order to Show Cause), with the demands by plaintiff for many of the documents at issue regarding the medical-legal exams. See: Luciano v Kennedy (Lefkowitz Decision). She also notes that Douglas Kennedy actually went with his lawyers to the final meeting with Dr. Elfenbein.

July 31st, 2015

Since lawyers like to share war stories, I thought I’d try something new and collect a few, if I found humor or abject stupidity in them. Abject stupidity includes asking the most useless questions possible at a deposition — so bad an 8-year-old wouldn’t do it.

Since lawyers like to share war stories, I thought I’d try something new and collect a few, if I found humor or abject stupidity in them. Abject stupidity includes asking the most useless questions possible at a deposition — so bad an 8-year-old wouldn’t do it.

Wait! Did I just offend some veterans by using the phrase “war stories” in the context of this trifling post? Wait again! Did I just upset someone by failing to publish a “trigger warning” before using the phrase “war stories?”

That preceding digression exists for a reason — this post is about language. Specifically, the unthinking use of it in the context of litigation.

This is inspired in large part by two things: The first is the collected trial quotes of the late U.S. District Judge Jerry Buchmeyery, at Say What?! The second is my own experience some years back in a 7-day deposition — a medical malpractice case dealing with a failure to properly treat an infection in the foot to a diabetic — where the lawyer asked:

When you started as a sanitation worker 20 years ago, what route did you work?

For the purposes of this series, if it ever progresses past this posting, I’m aiming for funny/ludicrous/moronic and utterly irrelevant.

Don’t ask me if there will be a part 2, ’cause I’m not as good as Judge Buchmeyer.

The names of the the parties and defense lawyers have been redacted to protect the guilty. All are original to this site, collected from friends. The first three:

————————

Submitted anonymously:

Q: Your mother and father moved to Chicago?

A: Yes.

Q: Your Father died?

A: Yes.

Q: Did your parents move to Chicago before or after your father died?

—————————-

Submitted by Mark Bower:

On the FOURTH day of plaintiff’s EBT with no end in sight, the mother testified that she had some (possibly relevant) papers in a black box on a shelf in her hallway closet. The defense attorney did not ask what the papers were, or what they said. Instead, she asked:

Which shelf?

What are the dimensions of the shelf?

How high is the shelf off the floor?

What are the dimensions of the box?

It finally ended when she asked “What color is the black box?”

At that point, I threw her out of my office. The loudly-threatened motion to bring the mom back for a continued deposition never materialized.

————————

Submitted by Jon Rapport:

—————————-

July 15th, 2015

Monday someone blocked me on Twitter. It’s the first time that has happened to me since I started sporadically using the service in 2009.

Me? Blocked? What malicious and impertinent crime had I committed?

Apparently, I committed the vulgar, discourteous and insulting crime of asking a law professor for a citation, and then discussing it. I kid you not.

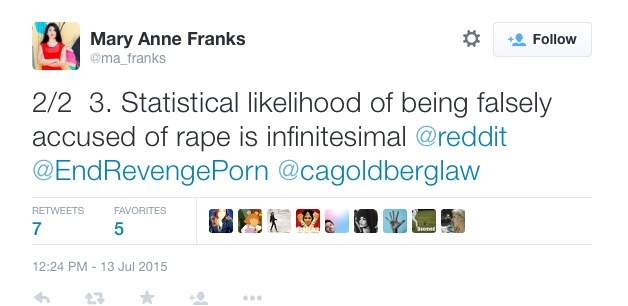

As I skimmed my Twitter feed upon return back from a delightful vacation, I saw this curious tweet from Professor Mary Anne Franks about the de minimis likelihood of a rape allegation being false:

Now I’m no student of rape statistics or studies for sure — it isn’t what I do, and it isn’t one of the issues I’ve routinely tackled in the 1,300+ pieces I’ve written here since 2006.

Now I’m no student of rape statistics or studies for sure — it isn’t what I do, and it isn’t one of the issues I’ve routinely tackled in the 1,300+ pieces I’ve written here since 2006.

But I was curious about the comment, certainly, since it carried a presumption of guilt, which is deeply at odds with our jurisprudence. And it was also at odds with stories in the popular press about rape accusations that turned out to be either questionable or outright false.

This includes such front page stories as the Duke Lacrosse players scandal, the poorly sourced Rolling Stone article from the University of Virginia for which it apologized (A Rape on Campus), Columbia University student Emma Sulkowicz who carried a mattress around campus after claiming she was raped, and the Central Park Jogger case. And, of course, there is the infamous case of the Scottsboro Boys.

But you know what the problem is with all those reports? They are not empirical evidence. While they discuss the facts of those particular cases, this means nothing for the big picture as to whether the incidence of false rape accusations is “infinitesimal,” or common, or somewhere in the vast gray area between.

While I don’t do criminal defense work, I do try civil cases, and I am aware of how stories in the popular press help to shape societal opinions (and, therefore, the jury pool). A classic example from my field is the McDonalds hot coffee case. I can’t remember the last time I picked a jury without discussing it.

The problem is that such stories are, by definition, outliers. If they weren’t outliers, they wouldn’t be on the front page where they then go on to shape public opinion.

Wanting to know the source of Professor Franks’ conclusion, I inquired with a very simple and benign citation request regarding her claim that false accusations of rape were “infinitesimal.” And with that she directed me to a Washington Post article that cited a variety of statistics, from different studies:

While I won’t summarize the entire article — since as you will see in a moment that is not the point of this post, and you can read it if you want — the author wrote about one significant study stating that there is “a profound disagreement on what counts as a false allegation.”

Due to the problem of shifting definitions (as well as unreported rapes), you can see by the article that it’s difficult to get a real handle on the extent of the problem. In fact, the very story that Professor Franks cited to me had studies showing false rape accusations varying between a low of 2% to a high of 45%.

The only thing that seemed to be clear about the statistics is that nothing was clear.

So I noted to Professor Franks that not only wasn’t the word “infinitesimal” part of the story, but that the very citation she gave me seemed to demonstrate otherwise:

And she blocked me. For challenging the conclusion she reached from her very own citation. This is academia?

Now where I come from, a lawyer doesn’t make an assertion that can’t be backed up with proof. Evidence is the heart and soul of any case or argument. I get challenged on my proof all the time, and I challenge defendants on theirs. Over the course of the 30 years since I was graduated from law school, I’ve become pretty confident that this is the way the system works.

The challenging of proof is what, hopefully, assists the finders of fact (be they juries or judges) to become the proverbial fly on the wall that determines what “actually happened” when one bit of evidence contradicts another.

It’s therefore routine in trials for each side to look at the opening statements of the other, and try to find some fact that they claim wasn’t proved at trial, and then pound away at this, calling it an exaggeration or falsity in an attempt to tarnish the entire case of the other side.

And that is why lawyers speak carefully in making assertions of fact, for otherwise we tarnish not only ourselves, but worse, our clients or causes.

I can’t help but wonder: What happens if a legal adversary challenges an assertion that Professor Franks makes in a motion or appeal? What happens if a judge challenges her cite? Will she stand in the well of the courtroom and try to block the judge?

And what happens when a student challenges a citation that Professor Franks gives in class? Does she block the student? Will she cover her ears and sing?

What kind of lesson does she teach her students by saying that, if a person challenges your citation, you just block them?

This post isn’t about rape. It’s about evidence. And teaching. And lawyering.

I’m reminded by this episode of an experience I had as a newbie blogger, with just months under my belt. Walter Olson at Overlawyered had written something and I posted an opposing view. So what did Olson do? He amended his post to read, And for another view, see Turkewitz. With a link.

This was the exact opposite of blocking. And it brought home to me in a heartbeat what the whole blogging thing was about. It’s about an exchange of ideas, some of which may be critical. Olson and I may butt heads on issues from time to time, but I’m indebted to him for that lesson.

And it was the subject of a post I wrote a few years ago celebrating that very fact (Twittering With the Enemy– A Blogospheric Celebration). Professor Franks would do well to take note.

A last thought. When I was a kid, I remember one of my teachers telling me that the best students were the ones that challenged their teachers with questions. This was the pool of students, he told us, from which he hoped would one day emerge a son-in-law.

Good teachers are happy when students’ minds are buzzing with inquisitiveness. Good teachers aren’t afraid of the questions. Or the answers. Or of learning something new.

Update (7.16.15) – In exceptionally stark contrast to Professor Franks, 9th Circuit Judge Alex Kozinski had this to say in an article that deals with his ideas (in part) on how to change the jury system:

If my proposals raise controversy and opposition, leading to a spirited debate, I will have achieved my purpose.

Now ain’t that refreshing?

———

Elsewhere, some on point, some tangential:

Professor Franks and the False Dichotomy (Jay Wolman @ Legal Satyricon, who was also blocked)

The ITIF’s Confusion on Free Speech and Revenge Porn (Scott Greenfield @ Simple Justice)

Professor Twitter and the Problem of the Low False Rape Narrative (Francis Walker @ Data Gone Wild)