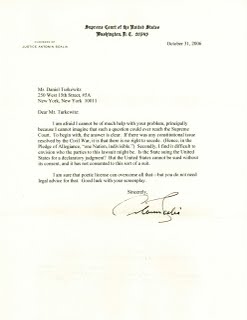

In responding to my brother Dan’s letter regarding the legal plausibility of Maine seceding from the union to join Canada, Justice Antonin Scalia raised two points. First, he said that the Civil War settled the issue of the constitutional basis for secession. Second, he indicated that he didn’t see how such an issue could even reach this nation’s high court.

I’m here today to take issue with both points before turning this blog (hopefully) back toward the personal injury field that is my bailiwick. With respect to the first assertion, Scalia’s exact words were:

If there was any constitutional issue resolved by the Civil War, it is that there is no right to secede.

There are no shortage of people willing to criticize such a position, because he simply states that might makes right. But the physically stronger side winning is not legal analysis, it is merely guns and tactics and doesn’t tell you squat about any legal basis. Many found that odd from a guy like Scalia who thrives on analysis.

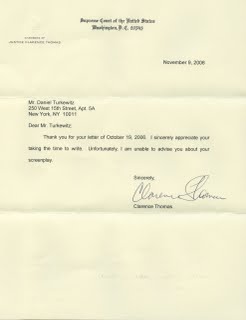

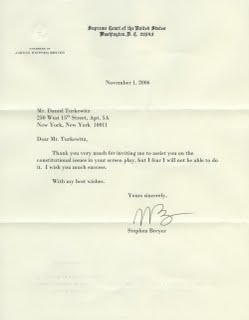

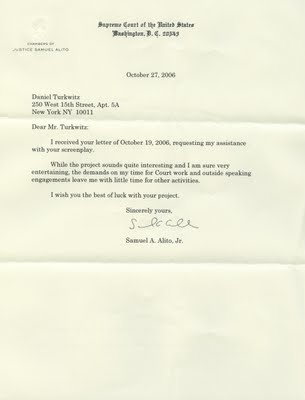

It is this first part that garnered almost all of the media attention that I noted yesterday when I published the rejection letters of other justices, and which Chris Matthews discussed on Hardball (brief video segment below).

But this post is really dedicated to Justice Scalia’s second assertion regarding who the actual parties to such a suit would be. And despite many dozens of blog postings regarding The Letter, I haven’t seen any discussion of this second point. Justice Scalia wrote:

Secondly, I find it difficult to envision who the parties to this lawsuit might be. Is the State suing the United States for a declaratory judgment? But the United States cannot be sued without its consent, and it has not consented to this sort of suit.

Well, let me take a crack at envisioning it: The United States is not party to the action for secession. Rather it is State v. State. Because if one state quits the union the others are saddled with the quitter’s share of the national debt. The other states, being unhappy about Maine (or Texas, Vermont, South Carolina, etc.) shirking its obligations, sue the departing state for its share.

And they bring that suit in the Supreme Court since the court has original jurisdiction to hear matters “between two or more states.” There isn’t any need for years worth of lower court legal wrangling, which is a nice bonus when writing a comedy for the big screen.

In fact, it’s this “It’s the money, stupid” plot line that my brother was using when he wrote to the justices, presaging the conservative Tea Party movement by three years. The set-up in the story, in a nutshell, has three University of Maine stoners in a midnight stupor in desperate need of a political science paper for the next day. They write up a manifesto on the vast sums of money that Mainers owe due to the rapidly escalating irresponsibility in Washington, and then urge Maine to join Canada. Manifesto, of course, is the charitable word for rant. The rant hits the college rag. The local paper picks it up on a slow news day, it strikes a chord with many and people press their state government to address the issue, which ultimately goes to a state-wide referendum as the political farce takes off. Our three heroes use their status as potential founding fathers to further the never-ending pursuit of weed and women.

A Supreme Court battle forms part of the script, albeit not a giant one because courts aren’t as funny as standard-issue politicians or stoners, with the other states insisting that if Maine leaves they take their part of the debt with them. It’s all about the money.

But wait!, I hear you say regarding the legalities. If a state has left the union then the suit is no longer “between two or more states.” A seceding state would most assuredly claim that the high court doesn’t have jurisdiction to hear the matter. Lack of jurisdiction is a common defense in suits, and a court must do an analysis to determine its merit when raised.

And therein lies the issue of how secession can land before the Supremes; the court must resolve a jurisdictional issue. In order for the court to resolve the merits of the money suit they must first decide whether or not the exiting state has legally left. If the state has legally left, the court can’t hear the case because it is not between “two or more states.”

This analysis seems backwards from the way jurisdiction is usually discussed. Merits generally come after jurisdiction has been established. But in this case the merits discussion has to do with money owed. And the issue of whether the court can even hear the case as a dispute between states must first be resolved, and that means looking at the issue of whether secession was legal.

How the case would be resolved in the real world is, of course, beside the point. This is, after all, a movie and the level of detail above wouldn’t be in it.

But Justice Scalia had written that he can’t think of how the matter of secession would get to the court. Well judge, I see how the issue can get to you. At least in theory. And it’s a pure jurisdictional question in a battle between states over money.

And for those wondering how, exactly, the Supreme Court could enforce a judgment against a seceding state in the event the court dumped the unhappy secessionists? Well, that has always been a problem since the judiciary doesn’t have a military wing to it. In 1957, the Army was called in on Executive Order to integrate Central High School in Little Rock. It remains a problem today out in Maricopa County, Arizona, where a court officer was caught on camera reading the files of a defense lawyer while she was addressing the court. The guy was held in contempt, and ordered to apologize on the courthouse steps. This was followed by a law enforcement sick-out. Enforcement can be tricky.

But the difficulty with enforcement of a court order is an issue separate from having the matter heard in the first place. Under this scenario, if a military solution were to be used to stop secession, it would come after a legal analysis of the merits.

Dan’s script, being a political farce, obviously doesn’t end with a military solution. I can’t give away more since it is just now being entered in competitions and my brother is still scrapping for an agent to represent him. (Anyone out there? Is this thing on?) But of his five finished screenplays, this is the best. And all the others have advanced in competitions.

So in the end, Justice Scalia, I think it can be done. Granted, I’m pretty far afield of personal injury law — you really can’t get any further afield than this — but then, so is almost everyone else that opines on the subject with the exception of a few scholars.

If I’ve completely blown the analysis — and I admit that despite its simplicity that is certainly possible — I’m sure people will let me know.

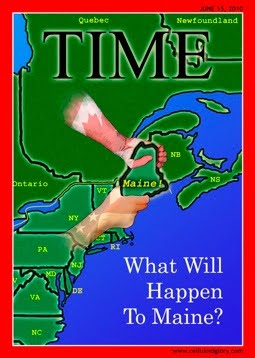

Graphic by Dan Turkewitz