While the corporate world may have been using teleconferences for awhile it is not part of the day-to-day activities of most practicing lawyers. And certainly not most personal injury lawyers.

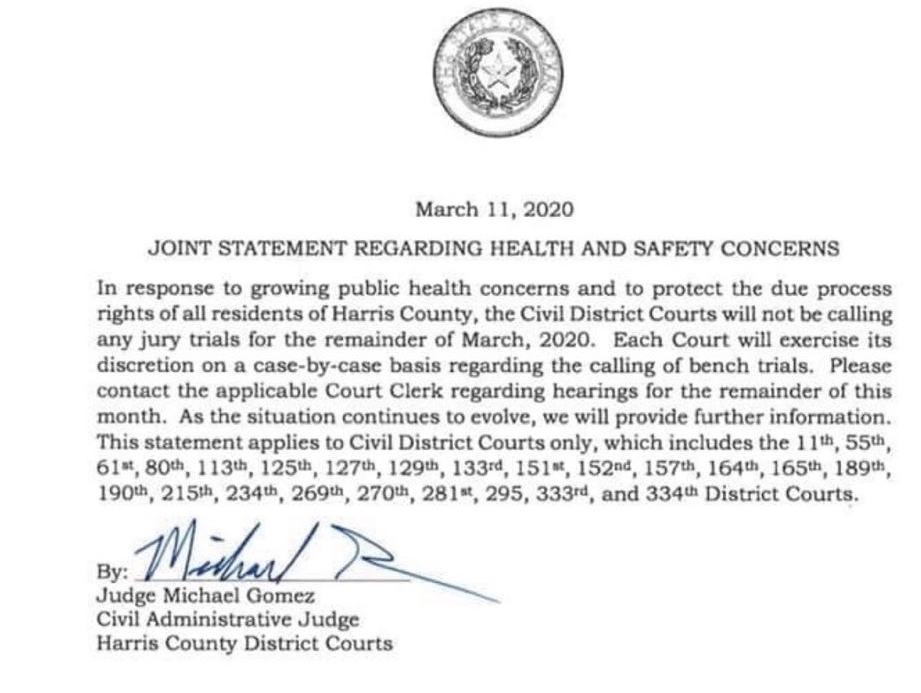

But with the courts substantially closed down — no trials and no conferences — lawyers are turning to teleconferences for depositions and virtual court conferences. So we damn well better get used to it fast.

Having now done three depositions this way over these past two weeks and several other teleconferences, I’ve a few short tips:

- Try to use a desktop that is hard wired to the internet to cut down speech delays. You don’t want a frozen image or dropped signal.

- Invest $50 in an external mic if your built-in isn’t good. If you want to be heard at a deposition or court appearance, having a distracting scratchy sound is not what you want.

- Put a light on in front of you so you are not backlit

- Use the mute button when not speaking so as not to inadvertently create background noise from typing, coffee cups, etc.

- Create a digital background if needed to eliminate clutter behind you (on Zoom, it’s in the settings). You can add whatever you want with a simple drag and drop of a neutral image if you like.

- Dress appropriately. Dress shirt and sport jacket for men for a deposition and the equivalent for women. If a court appearance, put on the suit. Because you might think you are only sitting in your kitchen, but you are really sitting in the judge’s courtroom. It’s not about where you are but about where you will be seen.

- For a deposition, do a video dry run with your client in the days before. You want your client to be comfortable.

- Do a dry run the day before with opposing counsel and the court reporter if there are any first timers. No one wants to be screwing around with technology when we should be focusing on facts and law.

- For depositions, make rules beforehand with opposing counsel regarding exhibits. Will they be marked beforehand and exchanged with the parties, or will you screw around with trying to email them to each other or (with some service) place them into a private digital box to be revealed during the testimony. The only real rule is this: Whatever you decide for one side goes equally for the other.

That should be enough to get folks started.