Most folks know that much of our criminal law is biblical. Thou shalt not murder, nor steal, nor bear false witness come right from the 10 Commandments.

But as my friend appellate lawyer Michael Altman points out to me, so too does much of our civil tort system.

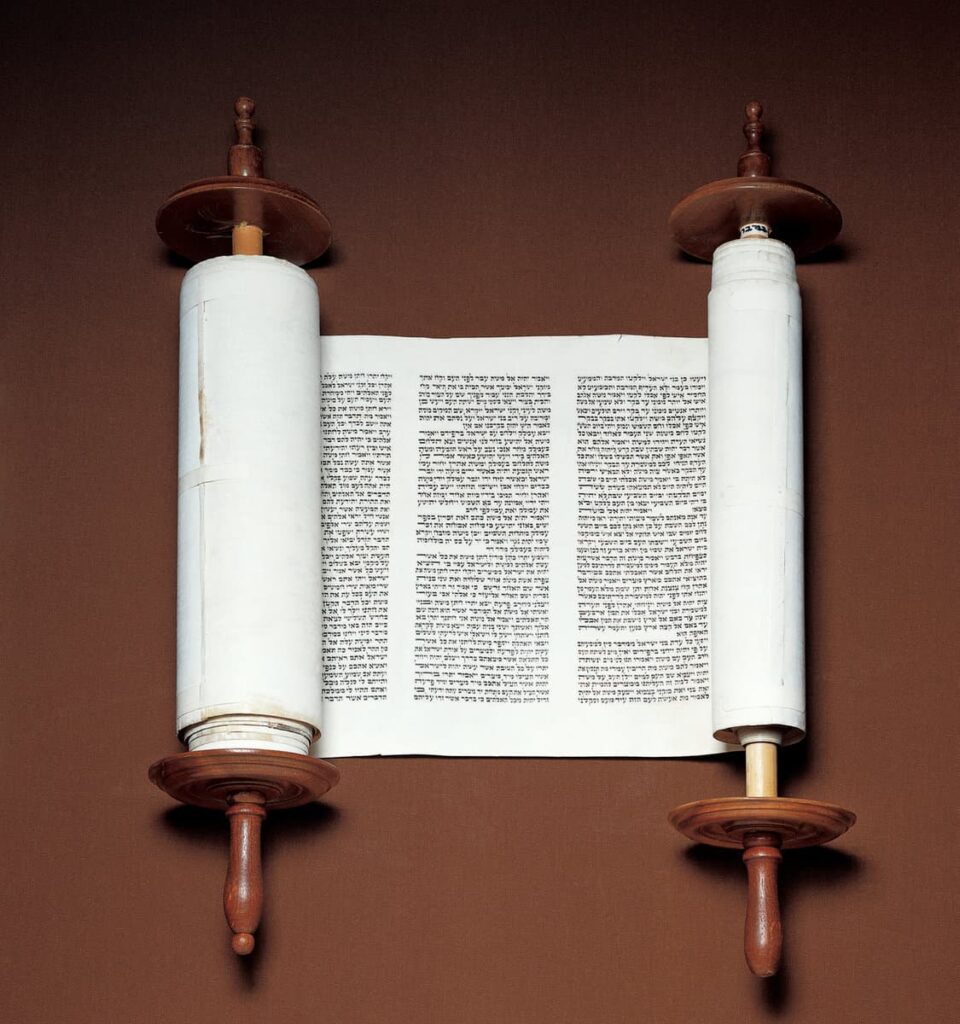

Last week’s Torah portion was Mishpatim, which means laws. Among other things it set up a civil justice system, which includes remedies for torts. As he reviewed the portion it struck him how relevant some of it is to what we do in the personal injury bar today.

Perhaps the most significant part is demonstrating just how far back a civil justice system that recognizes compensation for torts goes.

The citations below (of course there are citations, this is a law blog, right?) are from the Old Testament.

The most famous quote from that Torah portion is “an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth, a hand for a hand, a leg for a leg.” (Ex. 21: 24) You can almost hear Tevye quip, “Very good, and the whole world will be blind and toothless.” While a great line for Fiddler on the Roof, all rabbinic commentaries agree that it is not to be taken literally. Rather, it requires monetary compensation equal to the value of the lost body part.

The principle of compensation for personal injuries doesn’t just go back centuries. It goes back millennia.

In addition to requiring compensation for injury to a person, the Torah also recognizes the obligation to make restitution for injury to property:

“If a man takes his animals into someone else’s field or vineyard, and he lets them trample or graze in this other person’s field or vineyard, he must make restitution with the best of his field or the best of his vineyard.” (Ex. 22: 4)

Perhaps most importantly, it provides that all are equal before the law — rich and poor alike — as former Chief Judge Lippmann liked to note in advocating equality before the justice system:

“You must not pervert justice for your destitute countryman in his lawsuit.” (Ex. 23: 6)

Directly on-point with what Michael and I do, this part of the Torah also provides that one who causes or creates a dangerous condition is financially responsible for injuries resulting from it:

“If a person removes the cover of a pit, or digs a pit and does not cover it, and a work-bull or a donkey falls into it, the one responsible for making the pit must make restitution. He must restore the value of the animal to its owner, and the carcass remains its owner’s property.” Ex. 21: 33-34

And it provides for restitution for causing or creating a hazard:

If a fire breaks out and spreads through thorns, so that it consumes stacked or standing grain or a field, the one who kindled the fire must make restitution. (Ex: 22: 5)

The concept of notice is well known to the bar, and also here. It is not enough, for example, to make dog owners liable if their pooches bite someone. They must have first known that the dog had a known vicious propensity. This concept was not invented by us:

“If a work-bull gores a man or woman and the victim dies, the work-bull must be stoned; its meat may not be eaten. But the owner of the work-bull must be acquitted. However, if it was a work-bull that had gored on three previous occasions, and its owner had been warned in court but he did not guard it, and it then killed a man or a woman, the work-bull must be stoned. Its owner, too, will be put to death.” Ex. 21: 28-29.

I’d like to thank Michael for putting these quotes together, something that was well beyond my limited ability on the subject of Torah.

But I publish them here because people often see things through the lens of what happened today, or last week, or maybe a decade ago. But just a little bit of history helps put things in a different perspective.

(Law through the ages is part of a New Deal mural in the rotunda of the New York County Courthouse, including Babylonian Hammurabi’s Code and Hebraic law, among others).