Late Tuesday afternoon, a New York jury returned a blockbuster $50.5 million verdict for a brain injured, paralyzed scaffold worker. Daniel Savillo, who was 29-years-old on the date of the accident, had mis-stepped and fallen while working on a 15-foot high scaffold storage platform on February 12, 2007.

Since the owner and chief foreman had admitted that there was no fall protection provided to workers, Justice Emily Jane Goodman granted summary judgment in favor of Mr. Savillo in September of this year. That determination came in accordance with New York’s Labor Law. As Justice Goodman wrote:

Because Labor Law § 240 (1) “imposes absolute liability on owners who fail to provide adequate safety devices to workers laboring at elevated work sites, when that failure is a proximate cause of the workers’ injuries” , and because Greenpoint Landing provided no safety devices and that failure was a proximate cause of plaintiff’s injuries, that part of plaintiff’s motion which seeks summary judgment on the issue of Greenpoint Landing’s liability under Labor Law § 240 (1) is granted

With respect to the employer, All-Safe, Justice Goodman added in a footnote:

Given All-Safe’s complete disregard for safety (discussed infra), the name of this company strikes this Court as very ironic.

The nine-day trial before Justice Goodman in Manhattan (who also blogs for the Huffington Post) was, therefore, only to assess the amount of damages.

Prior to the trial, the plaintiff had rejected a settlement offer of $8.125M, holding firm in a demand for $14.5M. Given the breathtaking jury verdict, as well as the huge settlement offer that had been rejected, it’s worth taking a closer look at the verdict and damages.

As a result of the fall, Mr. Savillo suffered a complete cord injury at level T11 and had no sensation below an inch below his umbilicus. He had spinal surgery, screws, rods and cross-pieces placed in his back extending from from T7 to L2.

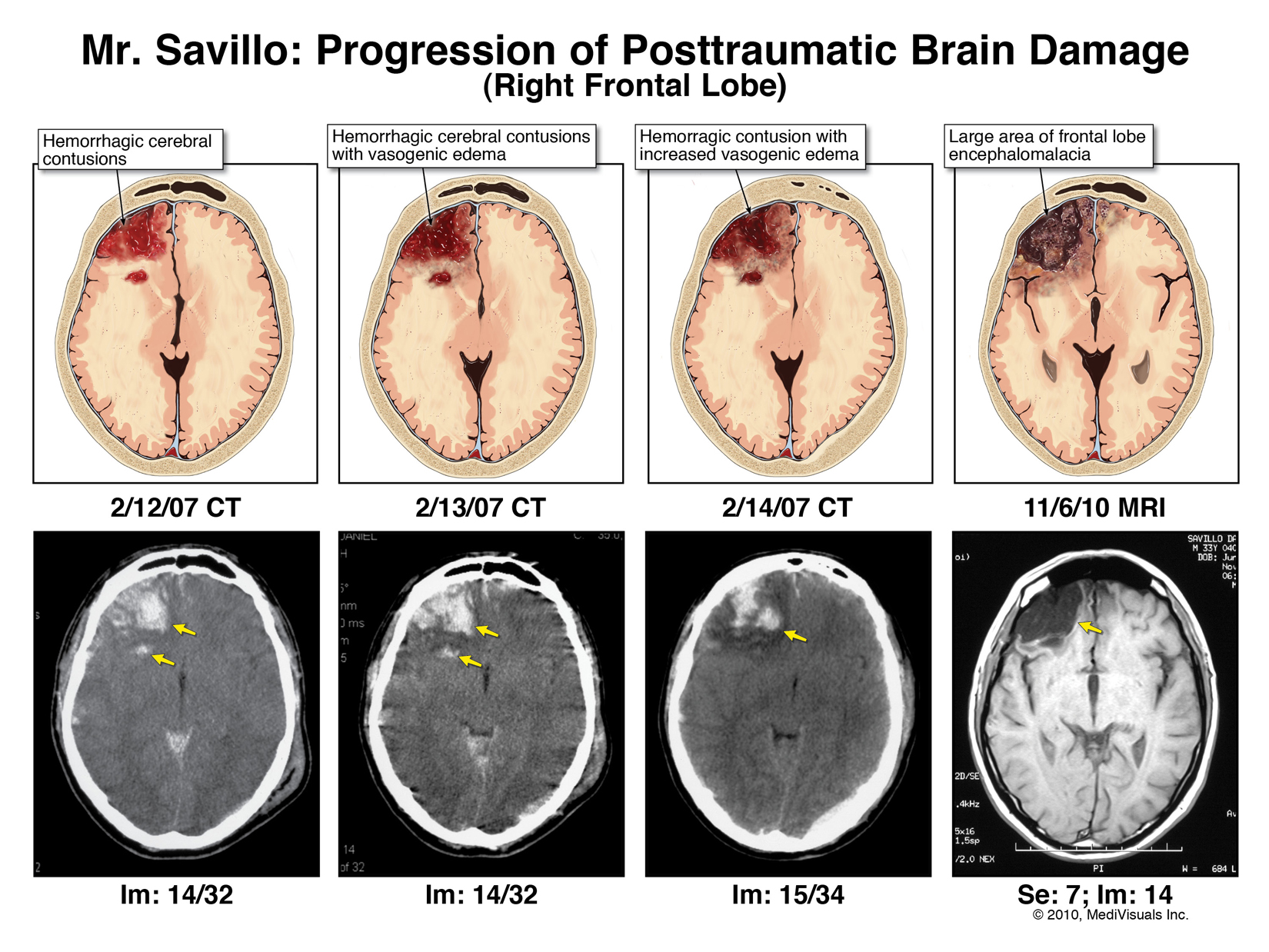

He also suffered significant brain contusions and hemorrhages, though no surgery was done on the brain. Evidence was presented of traumatic brain injury, with significant cognitive deficits, particularly in mental flexibility, information retrieval, processing speed, visual memory, short-term memory. He is unable to do more than a single task at one time. The progression of the brain damage can be seen from this exhibit that was used at trial (click to enlarge).

Other injuries consisted of a neurogenic bladder and bowel. This forces him to self-catheterize six to eight times each day for urination, and to manually evacuate stool after inserting suppositories on a daily basis.

- Past medicals expenses, approximately $600k;

- Past lost earnings, $200K;

- Past lost fringe benefits, approximately $50k

- A life care plan demonstrated over $9.224M for future medical care;

- Lost earnings and fringe benefits were approximately $5.6M;

- Past pain and suffering was $10M; and

- Future pain and suffering was $25M

The jury was unanimous in its determination. And of particular note, two of the jurors were lawyers. One was a fourth year tax associate at a major firm and the other works for the City of New York defending civil rights cases.

The plaintiffs called as expert witnesses: a neuroradiologist regarding the films, a rehabilitation expert, the neurosurgeon who repaired the spine an economist, and a vocational rehabilitation expert. The defendants conducted five separate defense medical exams, but didn’t bother to call three of the people that did exams (neurosurgeon, orthopedist and wound care surgeon). The plaintiff also called the defendants’ own rehabilitation expert on his own case, since his report was so devastating to the defendants.

The defendants called a neuropsychologist and an economist.

All of which is to say, that there were a lot of witnesses in a short amount of time.

A final word on the numbers. The jury total is about $50.5M. To that gets added interest, at a 9% annual rate, from the date that summary judgment was granted in September. From that gets subtracted certain things too. For example, the future economic costs must be reduced to present value at a later proceeding pursuant to CPLR 50-B. In addition, there may be a set-off for Social Security Disability payments that have been made, and with reasonable certainty will continue to be made going forward under CPLR 4545.

One can also assume that the pain and suffering verdicts will be challenged as excessive. How New York courts go about reducing (or increasing) verdicts from time to time was the subject of one of the first posts on this blog: How New York Caps Personal Injury Damages.

In other words, while the headlines will scream $50M, as this one does, the reality will one day be something else. And it will take quite a bit of lawyering to figure out what that will be.

The stars seemed aligned for a mega-verdict here, given the catastrophic injuries, that liability was already determined, that 9% interest would be running on any verdict (thus giving a comfort level to the plaintiff regarding the potential for defendants dragging out the litigation), that numerous experts were lined up and ready to go, that defendants had a fear of their own experts, and that an experienced trial lawyer was ready to take the verdict.

The case was Daniel Savillo v. Greenpoint Landing Associates, LLC (landowner) v. All Safe Heights Contracting Corp. (scaffolding co., employer). The plaintiff here sued the landowner, who turned around and sued the employer. In New York, those who are injured on the job generally can’t sue their employers under the Workers Compensation Law.

Plaintiff’s counsel was David Golomb, who is a past president of the New York State Trial Lawyers Association and a frequent lecturer on medical malpractice (and who I’ve known for many years). He is also a founder of Trial Lawyers Care, the massive pro bono effort put forward by the nation’s trial lawyers in response to the September 11 attack and the establishment of the September 11 Victim Compensation Fund. He was assisted at trial by Roy Jaghab, of Jaghab, Jaghab & Jaghab.

Greenpoint’s attorney was Edward Lomena.

All Safe’s attorneys were Scott Miller and Michael Manarel.