Much has now been written about the Supreme Court tossing out a $79.5M punitive damage award against Philip Morris in a smoking case where the compensatory damages were $821,000. Philip Morris v. Williams has been greeted by most as a victory for big business in limiting such awards (here, here and here). But it was not.

Much has now been written about the Supreme Court tossing out a $79.5M punitive damage award against Philip Morris in a smoking case where the compensatory damages were $821,000. Philip Morris v. Williams has been greeted by most as a victory for big business in limiting such awards (here, here and here). But it was not.

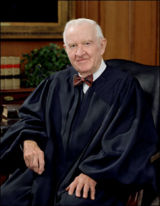

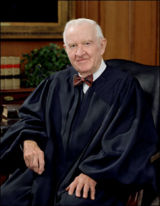

The key to understanding this is that Justice Stevens dissented. Stevens had formed part of the 6-3 majority in State Farm v. Campbell — the last significant ruling on the law of punitive damages — and State Farm had discussed much smaller ratios of compensatory to punitive damages, of 4-1 and 9-1.

Since Stevens voted to affirm the decision of the Oregon Supreme Court in Philip Morris, for the reasons stated in its opinion, this meant that a 100-1 ratio was within the bounds of acceptability to Stevens, and in accordance with his view of State Farm.

That State Farm majority ruling, often debated because of contradictory and confusing language, had held that an award of $145 million in punitive damages, when full compensatory damages were $1 million, was excessive and in violation of the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

So how much was too much, became the question that lawyers and judges have asked. Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion in State Farm, citing prior court precedent, said:

[W]e concluded that an award of more than four times the amount of compensatory damages might be close to the line of constitutional impropriety.

He also wrote that:

[F]ew awards exceeding a single-digit ratio between punitive and compensatory damages will satisfy due process.

This was qualified with the following:

Nonetheless, because there are no rigid benchmarks that a punitive damages award may not surpass, ratios greater than those we have previously upheld may comport with due process where “a particularly egregious act has resulted in only a small amount of economic damages.”

Kennedy’s majority decision had also said “We decline again to impose a bright-line ratio which a punitive damages award cannot exceed.” And he had further noted that the injuries in State Farm (as well as its predecessors) were economic, not physical, and that these ratios might not hold up if the harm was physical.

Notwithstanding the qualifiers that Kennedy gave, the 9-1 ratio has been cited, like some talismanic incantation, for the idea that corporate exposure to punitive damages was capped close to that level.

Justice Stevens, in agreeing that the 100-1 ratio was acceptable, and in doing so despite an $800,000 compensatory award, has now completely destroyed that argument. Of the seven remaining justices from the State Farm court, by a vote of 4-3 they would not disrupt the Philip Morris 100-1 punitive verdict based solely on the ratio. (Rehnquist and O’Connor had both sided with the 6-3 majority in State Farm.)

So, unless both Alito and Roberts in a future decision decide that the Constitution calls for some arbitrary protections against those whose reckless behavior injures others, high punitive damage multipliers will be allowed in some cases regarding personal injury. It is worthy to note, in that regard, that both Scalia and Thomas are against such limits and would form part of the new majority of such a decision if they persuade either of the two new justices to join them.

While Philip Morris v. Williams represented a set back for that particular litigant (it goes back to Oregon for further consideration), the overall effect of the Stevens dissent may be very bad news for corporate defendants if reckless conduct injures others.

For more on the subject:

Addendum: 2/24/07 — Upon further review, the case against a 9-1 ratio seems worse for businesses than I had originally stated. I reviewed the transcript of the oral argument, found here, and looked at the comments of Justice Breyer (in response to a comment left here by another). Breyer, in addition to Stevens, was part of the 6-3 majority in State Farm. At page 30, line 5 of the Philip Morris argument Justice Breyer states:

…the more severely awful the conduct, the higher the ratio between the damage award and the injury suffered by this victim in court. And if it’s really bad, you’re going to maybe have a hundred times this compensation instead of only ten times or five times. So — we take it into account, the extent of the harm that could be suffered, in deciding what that ratio should be. That means it goes to the evilness of the conduct.

Breyer seems to indicate that he would not stand in the way of a 100-1 ratio in the right circumstances.

Thus, even if Kennedy and Souter (both part of the State Farm decision) as well as new justices Alito and Roberts all voted for the strictest ratios possible on punitive damages, it wouldn’t seem to matter with the current court composition. The idea peddled by many of a firm 9-1 ratio seems dead in the water with a case involving personal injuries.

I think that any corporation that took comfort in the Philip Morris decision would be making a grave mistake. And while Philip Morris may have won this battle, if the Oregon Supreme Court again upholds the verdict, it appears that they will lose the war of numbers if comes back to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Update: 1/31/08: The Oregon Court of Appeals has once again affirmed the $79.5M punitive damage award.

(Eric Turkewitz is a personal injury attorney in New York)

This week DaimlerChrysler was hit with a $50M punitive damage award along with $5.2M in compensatory damages. In the wake of the Supreme Court’s recent 5-4 decision in Philip Morris v. Williams, many might wonder if this award of almost 10-1 ratio of punitive to compensatory damages will withstand judicial review.

This week DaimlerChrysler was hit with a $50M punitive damage award along with $5.2M in compensatory damages. In the wake of the Supreme Court’s recent 5-4 decision in Philip Morris v. Williams, many might wonder if this award of almost 10-1 ratio of punitive to compensatory damages will withstand judicial review.