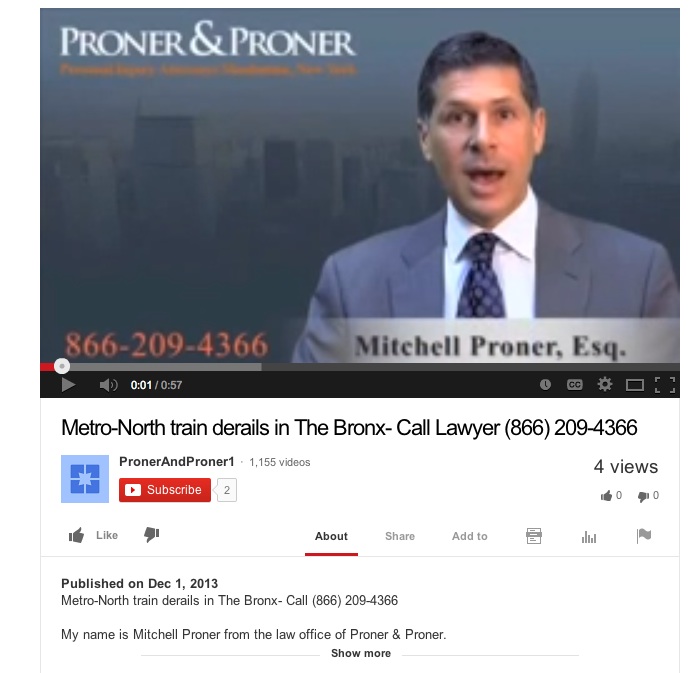

Screen Shot of Proner & Proner Ad on YouTube, 9 pm on December 1st, with YouTube noting it had been up for 11 hours.

Well, there they go again. It was just this past May that I took the New York law firm of Proner & Proner to task for stepping all over New York’s attorney ethics code with regard to a local train accident, and they seem to be back at it again. Yesterday’s deadly train derailment in the Bronx occurred about 7:20 am. The Proner law firm ran their first ad on YouTube within hours.

Let’s review, shall we?

In the wake of the 2003 Staten Island Ferry crash that killed 11 — and the race by some law firms to run ads in the Staten Island Advance before all the bodies had even been pulled from the wreckage — New York updated the Rules of Professional Conduct to stop the unseemly chasing of cases soon after a tragic event. This is our 30-day anti-solicitation rule:

Rule 4.5(a) In the event of a specific incident involving potential claims for personal injury or wrongful death, no unsolicited communication shall be made to an individual injured in the incident or to a family member or legal representative of such an individual, by a lawyer or law firm, or by any associate, agent, employee or other representative of a lawyer or law firm representing actual or potential defendants or entities that may defend and/or indemnify said defendants, before the 30th day after the date of the incident, unless a filing must be made within 30 days of the incident as a legal prerequisite to the particular claim, in which case no unsolicited communication shall be made before the 15th day after the date of the incident.

And just to be clear about what solicitation means, yes, it seems to mean doing something exactly like this — targeting a specific group. Read for yourself:

Rule 7.3(b) For purposes of this Rule, “solicitation” means any advertisement initiated by or on behalf of a lawyer or law firm that is directed to, or targeted at, a specific recipient or group of recipients, or their family members or legal representatives, the primary purpose of which is the retention of the lawyer or law firm, and a significant motive for which is pecuniary gain. It does not include a proposal or other writing prepared and delivered in response to a specific request of a prospective client.

I’ve written about this 30-day rule often, first after Captain Chesley Sullenberger splash landed a plane in the Hudson, then after a plane crash in Buffalo.

And most recently, I brought it up with this same firm, Proner & Proner, after another Metro-North derailment in Stamford Connecticut, when they apparently did the same thing they do today — use YouTube to solicit cases, despite our anti-solicitation rule. I counted stock videos uploaded in the hours after the accident, all of which have keyword loaded text to accompany it. See the screen grab above.

This makes Proner & Proner the second firm to get dishonorable mention twice on this blog for the same infraction. (The first went to Ribbeck Law after plane crashes.) I’m willing to bet, given that Proner has over 1,000 YouTube videos, that this type of conduct is probably standard procedure for them.

Why write about it again? Apparently, because those in charge of doing the disciplining either:

1. Don’t read this blog / didn’t notice; or

2. They did notice but don’t actually care enough to do anything about it.

I sure hope it is the former and not the latter, because the idea that the courts would institute ethics rules but not follow them isn’t a thought I like to contemplate. Since I happen to think that the 30-day rule works, I likewise think it’s important to enforce it.

It’s also important to note, as I always do when taking a firm to task when my eyes see as ethical issues, that there are very few firms that do this. But those that do serve to influence how the public feels about lawyers. And when I go pick a jury on behalf of my own clients, my clients are the ones that suffer from the deep cynicism that such conduct creates. This is not just my opinion.

Judge Frederick Scullin, Jr. sitting in the Northern District of New York in Alexander v. Cahill, wrote in a footnote about the reason for the rules:

Without question there has been a proliferation of tasteless, and at times obnoxious, methods of attorney advertising in recent years. New technology and an increase in the types of media available for advertising have exacerbated this problem and made it more ubiquitous. As a result, among other things, the public perception of the legal profession has been greatly diminished.

It should be the obligation of attorneys to improve upon the system of justice, not bring it down.