To the editor:

To the editor:

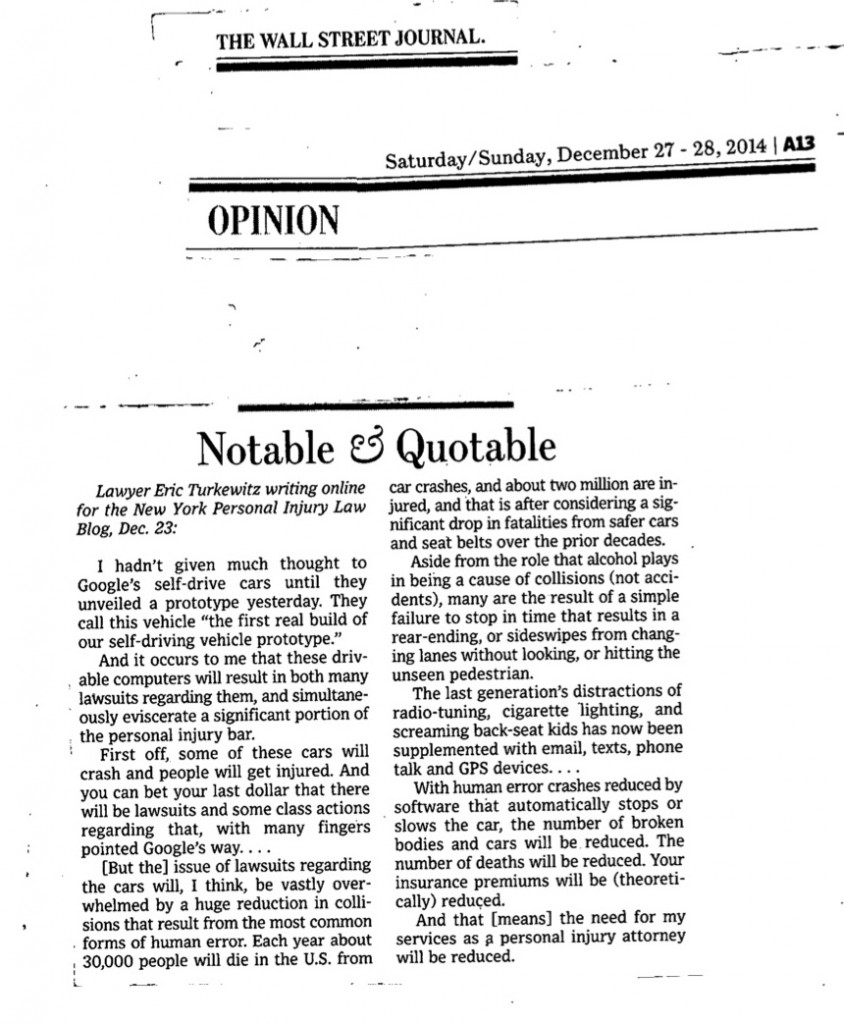

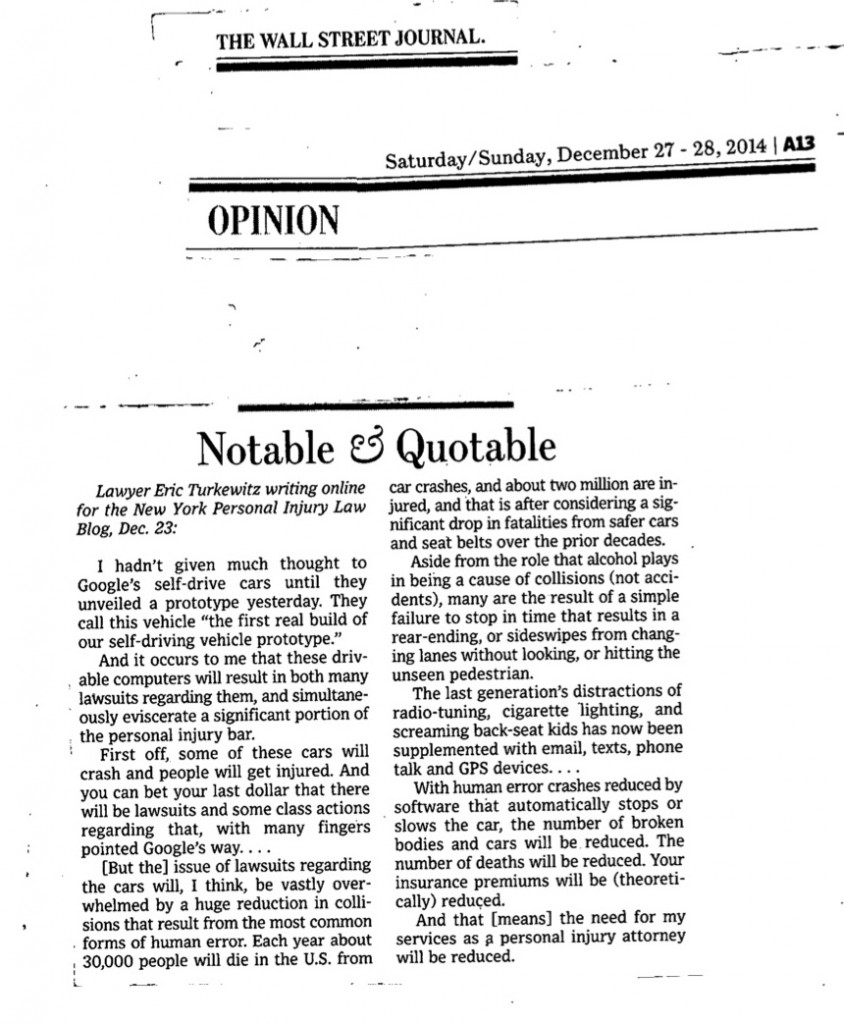

This past weekend in the Notable and Quotable area of your editorial section, you copied a long excerpt from a recent posting I made here. It was about Google Cars eviscerating the personal injury bar due to my expectations of improved safety.

I was struck with several different reactions:

1. It was nice of you to notice the piece. I’m both Notable and Quotable in the WSJ. I wish my family felt that way. Aww shucks, and all that.

2. My, oh my, you certainly copied a big chunk of my piece, didn’t you? A word count shows you took 44% of my post. That sure is a lot given our copyright laws, isn’t it?

3. Didn’t you think it might be worthwhile in the online version to supply a link so that readers would understand that my posting was a celebration of the diminution of my business, and not a complaint?

4. Most importantly, don’t folks rip off your content all the time? And don’t you complain? What kind of example are you setting for others?

It’s this last point that I want to dwell on — though I think your selective editing on #3 is pretty important — because it seems that such wanton copying only encourages others to do the same. This is part of that whole moronic “content wants to be free” claptrap that is prattled by those who’ve never created anything.

Now you might think, hey, we can just take your words under the “fair use” doctrine! But 1st Amendment guru Marc Randazza seems to say otherwise, and he isn’t particularly kind to you in doing so. Randazza writes,

As someone who blogs, it bugs me when other people steal my work and re-post it on their own blogs. It bothers me even if they provide a link back. Why? Because fuck you. This is my work. If you want to quote part of it, you’re most welcome. You feel like you need to do a large block quote? Go ahead. You hate it and want to ridicule it? Go ahead. You think I’m awesome? You must be sick.

What I’m getting at is fair use is fine, but just ripping off my shit is douchetastic.

Yeah, he’s colorful. But that lede is also followed by him understanding the gist of the piece, as opposed to your selective edits to take it out of context:

The theme of Eric’s article is that self-driving cars may cut down on accidents, insurance rates, deaths, etc., and he actually states that he cheers the thought that he might be put out of business.

Interestingly enough, the Wall Street Journal cuts off its plagiarism right before Eric makes that point. Instead, the WSJ dishonestly makes it look like Eric is whining that he won’t have as much work.

Ok, being quoted out of context? That’s all part of speaking in public. Some douchebag will always do that.

Like me, Randazza — who was my counsel in Rakofsky v. Internet — understands that quoting out of context isn’t the real problem. We both write in public and when we do so we put on our big-boy pants and deal with it.

No, the real problem is theft. You weren’t commenting on what I wrote, the way Jacob Gershman did in his WSJ Law Blog post. You simply cut and pasted my work onto your editorial page without asking.

Randazza goes on to the far more important fair use (or lack thereof) argument, one that should be second nature to you and your lawyers at the WSJ:

But what really bothered me about this is how the WSJ simply stole Eric’s work, and couldn’t be bothered to actually do any of its own — except putting the plagiarized portion next to some ads. They put it in the print version too.

And that is not fair use. It is even more ironic and douchey when you know that Eric’s work is on the WSJ [website], but behind a paywall.

I know that the WSJ must have lawyers on staff. I can’t imagine why they never learned anything about fair use. Because this is not fair use.

If you want the details, and the law of how you screwed this up, because your lawyers may be on vacation this time of year, go read Randazza’s full piece. He’s even kind enough to cite case law for you. I’ll give you a hint though — and this comes from a guy who defends this stuff all the time –he’s pretty clear you fouled up:

Ultimately, the WSJ blew it here because they didn’t add anything to the original — they just lifted it and reposted it.

So now what do you do?

Well, here’s my suggestion: You write me a nice note that says, “Oops! I can’t believe we just took so much of your property and reprinted it without asking! We really shouldn’t have done that.”

Well, here’s my suggestion: You write me a nice note that says, “Oops! I can’t believe we just took so much of your property and reprinted it without asking! We really shouldn’t have done that.”

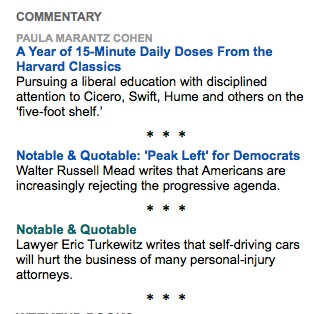

And you also say that you shouldn’t have made it look, on your index page, as if I submitted it to you in this fashion, as seen in the graphic to the left, since I played no part in its appearance there. And that if you were going to edit my piece to imply something different, then a link should have been provided so that your readers could see full context.

Then you say, “What can we do to make this up to you!?”

And I say, because I’m a nice guy and willing to give you the answer in advance in case you are worried about lawsuits, “You owe me a beer and we’ll call it even.”

Why would I let you off the hook so easily? Because I have bigger concerns than the 12 rupees you might owe me for swiping my stuff without permission, that concern being your implicit endorsement of such practices.

Because that endorsement hurts all writers, both you and me together. (I know, it’s gotta suck for some at the WSJ to be in agreement with a personal injury attorney.)

And you say to me, “Wow, we’ve never received such a nice lawyer letter before! And your suggestion that we admit an error sounds perfectly reasonable, because if we don’t admit it was an error, others that copy our stuff might possibly throw this little theft back at us one day as a defense, ‘Hey, if youse guys at da Journal can steal 44% of that idiot-lawyer-blogger’s content, why can’t we just take 44% from youse, huh?’ ”

You’ve probably never been offered such a good deal, that being the actual, real-world benefits of saying “oops.”

Now I know that you probably get pitched a bazillion times a day from kings and queens, presidents and prime ministers and all manner of CEOs and genuflecting flacks trying to use your paper as a forum for their brilliant thoughts and ideas. You might simply have thought I’d be grateful to have my words appear in your august periodical in its widely read editorial area, even if you didn’t ask me and you selectively neutered out the main point.

But what you did was wrong from a much broader and fundamental point than a simple copyright violation of my little blog. You violated the ancient Golden Rule: If you steal from others then you can’t complain when others steal from you.

I await your oops letter. And my cold beer. It’s for your own good.

Your new bestest, BFF and beer drinking buddy,

/s/ E.T.

Updated P.S. – I should have also noted, when writing this story, that you are in good company. Both the Daily News and the New York Times have likewise ripped me off, with the details at those links.