Christine Blasey Ford, by Manuel Santelices. Used with permission.

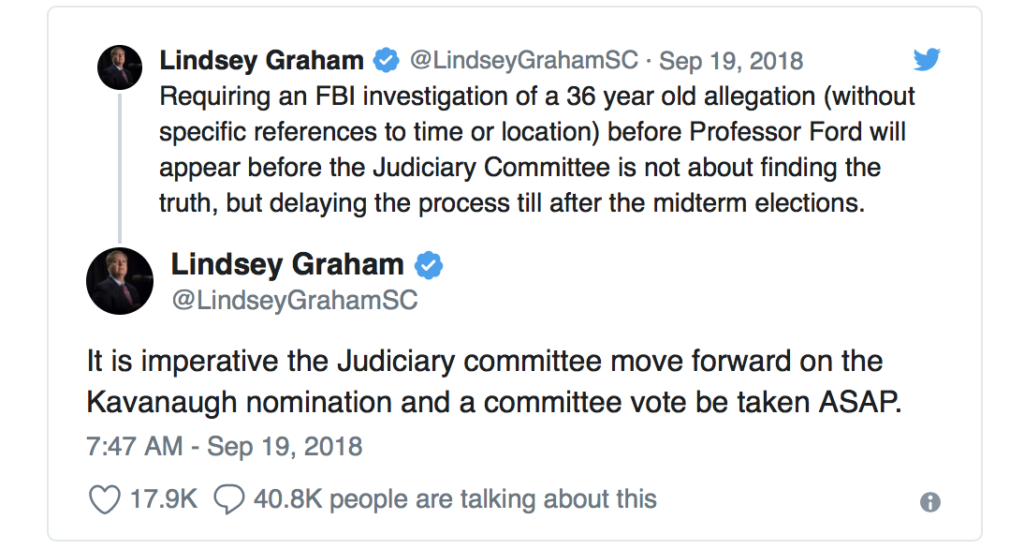

Much will be written about the horror show yesterday before the Senate Judiciary Committee regarding the emotional testimony of Dr. Christine Blasey Ford and Judge Brett Kavanaugh. While there will be a million hot takes on its immediate significance, I’d prefer to look long term at the damage to the Court as an institution, and how to fix it.

Already suffering from deep politicization –made worse by the failure to the GOP to even give Judge Merrick Garland a hearing — it seems that the Court is doomed to have whatever shred of its integrity and dignity destroyed unless the Nation acts.

Over at Reason, however, Nick Gillespie sees no hope, and calls it “impossible.” In an article he wrote before the hearing, 3 Questions To Ask Yourself While Watching the Kavanaugh/Ford Hearings Today, he writes:

Is there any way to depoliticize the selection of Supreme Court justices? Almost certainly not, and it probably would be inadvisable in any case. The Supreme Court is part of the government after all, and the justices read the opinion polls and headlines too. They are selected by one politician (the president) and vetted by others (senators). Getting politics out of the process is impossible and ultimately, elections do indirectly change the makeup of the bench.

I disagree and offer my three ways to restore the integrity of the institution.

But before doing so, it’s important to note that when the Constitution was written, the average life expectancy was 36. When you factor out all those that died in infancy and childhood, you obviously got a higher age, but it still would not have compared to today’s average age of 78. Serving on the High Court was the culmination of a career.

Now, however, it is seen as a way to put someone on the Court for 30-40 years, thereby making each seat that much more potent. When you combine that with Congress’s continuing refusal to make tough decisions and instead pass its power to various agencies that make decisions without voter approval, you get a Court made even more powerful by virtue of the breadth of issues it must decide.

So how to deal with this? My three suggestions:

Term Limits. This is not a new idea and has been kicking around for awhile. If each jurist gets an 18 year term, with a new one picked every two years, you have regular turnover that reduces the impact of any one justice. After leaving the Court the judges can sit by designation in any District Court of Court of Appeals of their choosing, as retiring SCOTUS justices do now, and do so for life.

Pinch Hitters. As we saw with the Garland nomination, Senators have a motive to leave seats empty until a President comes along from their own party. This is, obviously, an insult to the Constitution. If the Democrats get a chance to get revenge and hold a seat open until the next election, they surely will do so. Additionally, there is sometimes an empty seat when judges must recuse themselves due to conflicts of interest, which was the subject of a satiric April Fool’s gag I wrote 10 years ago that had various justices recusing (or not) based on their participation in a fantasy baseball league. The gist of it was the recusal rules aren’t really all that clear and justices decide for themselves.

The solution? If there is a vacancy due to death, retirement or recusal, the Court pulls a name at random of a sitting Court of Appeals judge with 10+ years on the bench to sit by designation. This decreases the chance of Senators playing politics with the Court.

Advice and Consent. The Constitution says the President appoints the judges with the “advice and consent” of the Senate. But all too often, it seems, there is a request for consent without asking for that advice. The Judiciary Committee can agree, and make part of its rules, that it will provide to the President a list of 10 (or 20, or whatever) judges and that a hearing will be given for any one culled from that list. This, of course, requires actual cooperation among the Senators, who would choose the list members by a supermajority, thereby taking another step toward removing politics and eliminating extremist choices from either side. It would only be effective, obviously, after the next election.

But you know what? This all presumes that the Senate actually wants the Court to be immune from politics. The more cynical view, and perhaps the more accurate one, is that Court nominations and fights are just another means of generating anger, which is then used for fundraising purposes.

So there are means out there to depoliticize the court. It can be done. The question is whether there is the will to do so.