When I was a puppy lawyer my father gave me this advice about witness preparation: Never tell a client what not to say. Our conversation went like this:

Dad: If you tell a witness what not to say, the witness will blurt it out.

Me: Huh?

Dad: If you tell the witness, “Under no circumstances should you ever say Rumpelstiltskin” then the deposition will go like this: What’s your name? Rumpelstiltskin.

As Mitt Romney can attest, my dad was waaaay ahead of his time. In an article by Liz Goodwin on Yahoo! News (Why Mitt Romney can’t shut up about his money) she finds Romney has the same problem that my dad focused on when it comes to talk of wealth. Romney’s obviously been told, again and again, not to discuss it. And out it comes, time and again:

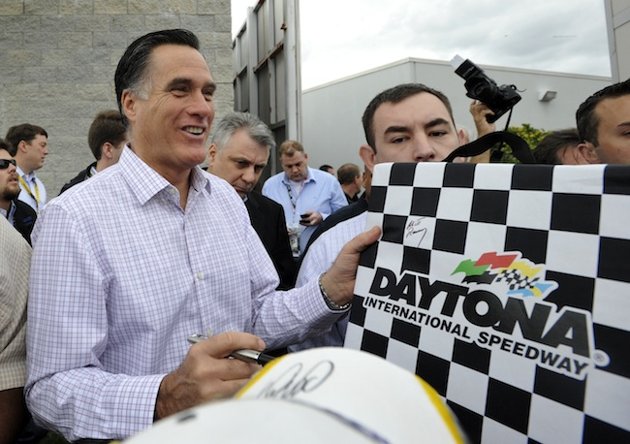

Over the space of a few months, private equity millionaire Mitt Romney has cavalierly bet a Republican rival $10,000 during a debate, enthused about the joys of “being able to fire people who provide services to me,” told Detroit voters that his wife drives “a couple of Cadillacs,” and said at the Daytona 500 that while he is not an ardent fan of the sport, he does have “some great friends that are NASCAR team owners.”

Goodwin delves into similar cases, from literature to baseball, about individuals stridently trying to avoid saying/doing something, and the problems inherent on focusing the mind that way.

This matters, of course, in the context of litigation if a lawyer tries to over-prepare witnesses by telling them what to say or not say, as opposed to finding out what happened and dealing with that. The witness, in the uncomfortable spot of a court proceeding and directed to do something that might not come naturally, will sometimes blurt out what the lawyer tried ever-so-hard to stop them from saying.

Goodwin explains:

This is because our brain is always helpfully looking around for the very worst things we could do or say in any given situation, and then actively trying to suppress them with other, more appropriate thoughts and actions. The process has two parts–the unconscious, automatic monitoring of our forbidden thoughts, and the conscious, effortful way in which we distract ourselves from it. So when a person is trying not to think or talk about something–say, to pick an example at random, his personal wealth–he needs to both monitor the forbidden thought and distract his mind with other thoughts. This is called the “ironic process,” and it usually works, otherwise we would always be blurting out our secrets and insulting our loved ones.

Thus, today’s lesson in law: Beware the danger of trying to demanding a witness say or not say something, as opposed to finding out what happened. That, of course, is in addition to the ethical issues of having a witness fail to tell the truth.

There’s a lot more in the article, and it has strong relevance to the subject of witness preparation.

Probably sound advice.

It might even work with the normal run of client. I like to find out what happened in advance of deposition just to avoid surprises. It also helps to have a little advance time to look into whether there are mitigating facts: “Yes, I ran over the old lady. After she shot two rounds through the windshield and jumped in front of the car as I was trying to get away.”

However, occasionally I see the hard case. How do you successfully advise a client _not_ to tell a particularly implausible lie that (a) they think is a winner (b) will cook the case for them?

Hahaha! Great advice.

Lending support to your dad’s theory, I think Romney’s $10,000 wager came within 24 hours after the NYT ran a piece on him, the whole point of which was to paint an image of him as “thrifty.” http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/11/us/politics/two-mitt-romneys-wealthy-man-thrifty-habits.html?pagewanted=all

The advice I give the witnesses is to think about what was asked, and answer that question and no more. Don’t take the question as a cue to give a soliloquy.