On July 16, 1969, Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins sat atop a Saturn V and blasted off to history. And our imaginations lit up regarding what was, and what could be. Woodstock and the improbable worst-to-first Amazin’ Mets followed shortly.

New York Appellate Lawyer Jay Breakstone takes a look back to the summer of ’69 today, as we take a break from posts on Judge Sotomayor…..

————————————————————-

The strong flow of events is like a river. It can carry even the most wayward leaf along for the ride. In the summer of 1969, I was surely that wayward leaf. A disastrous freshman year at an upstate New York college had uncovered two primal truths. The first, was that I was not to be a doctor like my father; the second, that you don’t take a city boy from East Flatbush and put him in a town where Andy Hardy takes Polly to the prom. I was depressed and lost, with no center to my universe and no direction known.

Enter Neil Armstrong. I had spent most of my then 18 years living with the American space program. I had dawdled in front of the TV when I should have been running to school, hoping that there wouldn’t be any holds so I could see a Mercury or Gemini launch live. Inevitably, the primitive digital clock on the screen counted down and the worst thing imaginable would occur – – the voice of Col. John “Shorty” Powers in Mission Control announcing a delay and sending me off to school unsatisfied. But as the summer of 1969 approached, I realized that all those unrequited mornings would soon be vindicated. The Russians had failed and we had succeeded. We were going to the Moon. Maybe I was mired in failure, but Neil and Buzz were not.

Somewhere along the way, though, I had decided that I didn’t want to look like Neil and Buzz. The John Glenn crew cut didn’t work for anyone other than astronauts (and those kids in that upstate town). I had attended New York City’s Stuyvesant High School, hotbed of intelligence and activism. I had marched for equality and to end the war. In a culture that still required its high school students to dress appropriately, we at Stuyvesant did not. We wore sandals (if we wore shoes at all) and carried knapsacks. Most important, we had long hair and more respect for Mark Rudd and Johnny in the basement mixing up the medicine than for Richard Nixon.

Necessarily, this caused just a bit of friction at home. My doctor father had flown B-24’s in World War II. He had that John Glenn crew cut. He believed in Vietnam because he believed in America. He was a hero. I, however, was none of these things. Moreover, I had just demonstrated that I was not much of a student either. We talked a lot that summer of ’69 and, like a huge ocean liner, my father began a slow turn. Vietnam ceased to make sense to him and Woodstock suggested that perhaps his son might have a different way of looking at the world that was not quite as foolish as he had once believed. If there is a time for every purpose under heaven, that summer allowed me to ride the good vibrations of Woodstock into my father’s heart, a place where I had never really left in the first place.

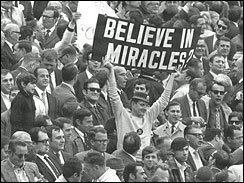

The pulse of the times can substitute for the vitality of the individual. All you have to do is be clever enough to hop on board. The summer of 1969 was a veritable freight train of optimism. We could stand on the Sea of Tranquility and we could stand in the mud of Max Yasgur’s farm. It was all good. A small town college could give way to a large city university. Science and math could surrender to writing and literature. The dream of medical school could disappear and be replaced by “maybe I’ll go to law school.” In the summer of 1969, anything was possible. How did I know? Because the New York Mets were on their way to the World Series.

My life then had been short, but not so short that I hadn’t sat in the stands of the Polo Grounds in 1962, where the woeful Mets played before Shea was built, wondering whether anyone on my team could play this game. Off in the distance, beyond the hills of Coogan’s Bluff, sat the Palace of the Hated, Yankee Stadium. There, a real baseball team played. To them, it wasn’t a game. Baseball was serious business there. Tell that to Marv Throneberry, my first baseman, who made every pop fly a cosmic experience. Would the gods let Marv catch it or wouldn’t they? It seemed to have nothing to do with Marv. I was born and bred in Brooklyn. My mother had been a crazed Dodger fan, so much so that my Bronx-born father was never permitted to say the “Y” word in our house. By the time I was old enough to go to a ballgame, my team had left for California. I was rudderless on the sea of sports fandom. My early years were taken up by watching roller derby instead.

In that summer of 1969, however, anything was possible. I sat in the old Dodger Bar and Grill on the corner of Flatbush and Fulton, watching the games on the color television propped high in the corner. It was hot that year and the coolness of the dark bar calmed me. So did the cheap beer on tap. I sat and tried to figure out what to do with my life and watched the Mets do the impossible with theirs. Me, the Mets and three old guys who had not left that bar since the Dodgers won the World Series in 1955. They had waited in that very bar since then for the lightning to strike again. They had grown old waiting. Their families had lost track of them; written them off as dead. Detectives had closed Missing Persons files and shelved the boxes in closets marked “Unsolved.” Yet, here they were, like Macbeth’s three witches. For all those years they had been conjuring, stirring their Four Roses with a Rheingold back, invoking the baseball gods. In the summer of ’69, when anything was possible, it happened.

I know that these things happened, because I was there. In the summer of 1969, I was born again. I floated along on that river of the impossible and let it take me where I didn’t have the strength to go by myself. We kept going back to the Moon, the Mets won the World Series and even the Jets won the Super Bowl. Woodstock became synonymous with a better place where better people lived a better idea. I guess I was lucky. The time warp had opened, but only for a moment. God had smiled for an instant. Within a year, it would all be over. There would be four dead in Ohio, my mother would tell me that I shouldn’t worry about the draft because she wasn’t letting me go anyway, and my father would be dead. Oh, and I would be well on my way to law school, but I didn’t know that at the time either.

———————————————————————–

Jay Breakstone did, indeed, make it to law school, and was sworn in eight years after this legendary summer. His current email is NYAppeals [at] gmail [dot] com.

So much happening back then. I can only imagine. As for me, I am an 80’s child. Yeah, the era of Michael Jackson, new wave, etc.

# posted by Anonymous BloggerPal : July 14, 2009 11:07 PM

We have more technology now then back in the 60’s and way more opportunities to make change…It just seems like the ambition to do so is gone and society has a lost hope to just maintain its ways.

# posted by Anonymous Gibson/Simon : July 21, 2009 1:09 PM