Every personal injury victim that has a case worth taking should have a story worth telling. And there are a million ways to tell it at trial.

Every personal injury victim that has a case worth taking should have a story worth telling. And there are a million ways to tell it at trial.

The ability to tell that story — in an engaging manner that keeps the jury interested while you dot the “I”s and cross the “T”s of evidence — goes to the heart and soul of standing in the well of the courtroom. Those that mechanically travel the linear path from start to end are likely to lose the interest of the jury, and if their interest is lost, so too are your arguments.

When I open, I like to start the story in the middle. It is that particular moment in time, perhaps, when a patient walks into a doctor’s office, or a car crosses the double yellow line to the wrong side of the road. It goes to the essence of why you have risen from your chair to address the jury.

And when I say I like to start in the middle of a story, I’m not kidding. I don’t waste time thanking the judge, or the jurors for their presence in the courtroom. I don’t introduce myself or my client. Chances are, much of that has already been done anyway, but if not, I can get to it later. I need to tell them why they are here. Because they want to know.

You’ll never have greater command of the jury’s attention than that first 60 seconds of a trial. You can waste it with platitudes the jury doesn’t care about, or you can use the time wisely. And so I begin,

“Today we turn the clock back to January 5, 2004. Jane Patient is showing a hard lump in her breast to Dr. Gyno, explaining how she found it while washing herself in the shower, and of her intense anxiety over its appearance. Dr. Gyno, who Jane has trusted for years, examines the lump for a few seconds, and tells Jane not to worry about it.”

The jury now knows why they were dragged from their homes or jobs to sit in this courtroom. They know, perhaps intuitively, that Dr. Gyno likely has a different version of events, but that this is the sharp issue of fact that will define the trial. They have also been presented with a moment of anxiety and stress by your client that may be the essence of one of your themes — betrayal of trust. Most importantly, they want to know the details.

From there one can fill in the before and the after, introduce people in the courtroom, witnesses that may appear, and slowly work into the story the various elements. But it is a story you are telling in the trial — often an emotional, gut-wrenching story that brings the concepts of life and death into sharp focus. This cannot be told in a rote beginning-to-end manner.

Sometimes finding the middle doesn’t seem easy. If you were telling your friend about running the NYC Marathon, would you start with your decision to run or the months of training that went into it? Doubtful. The “middle” of such a story may be the moment of greatest anxiety and anticipation: The starting line as you wait for the deep thump of the cannon while looking out across the Verrazano Narrows Bridge, where the great footrace starts.

Telling the narrative can take you into a thousand different directions. There is really no “right” way to do it, other than to stop orating like a lawyer and start talking like a storyteller.

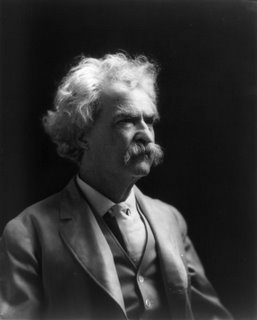

Mark Twain, not a keen fan of attorneys, was a master. On this subject he wrote:

“Narrative is a difficult art; narrative should flow as flows the brook down through the hills and the leafy woodlands, its course changed by every bowlder it comes across and by every grass-clad gravelly spur that projects into its path; its surface broken, but its course not stayed by rocks and gravel on the bottom in the shoal places; a brook that never goes straight for a minute, but goes, and goes briskly, sometimes ungrammatically, and sometimes fetching a horseshoe three-quarters of a mile around, and at the end of the circuit flowing within a yard of the path it traversed an hour before; but always going, and always following at least one law, always loyal to that law, the law of narrative, which has no law. Nothing to do but make the trip; the how of it is not important, so that the trip is made.”

(Hat tip to Bryan Garner, Quote of the Day, 4/11/07)

(Eric Turkewitz is a personal injury attorney in New York.)

Agree whole heartedly there is no “right way” to tell the story. But through practice and jury research even the very best advocates can get better at telling the story for a particular case or client. Focus groups help the trial lawyer accomplish both of these and facilitate the telling of the story in the best way possible. I wrote using focus groups to help tell the story at trial today on my blog… [Ed. Link removed as it didn’t go to a blog post regarding the aforesaid focus groups.]