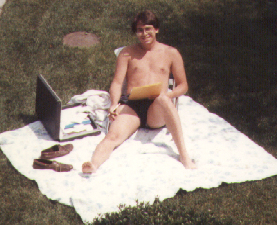

Studying for the bar on the front lawn of parents’ home, summer of 1985. That’s not a laptop — it’s a briefcase.

Oh gosh, I don’t even know where to begin. So I’ll just type and see what flows.

I remember standing there on January 15, 1986, in the well of the courtroom at the Appellate Division, Second Department, hearing my name read as part of the roll of freshly minted law graduates. Despite a small hiccup because my bar exam answers were lost, I was ready.

And thirty years ago today I was sworn in as an attorney. Ronald Reagan was President. Martin Luther King Day had just become a federal holiday. Chernobyl would soon melt down in the Soviet Union. And the subway was $0.90 and still used tokens.

I’d already been working for months as a “non admitted attorney” or “J.D.” or however else it was that I signed my name to letters back then, to qualify that I wasn’t actually authorized to stand on my own yet before a court.

But once admitted, I was quickly tossed into the litigation fire. And with that, there was one Golden Rule I was given: For the first year, there was no such thing as a stupid question. My mentor understood the risks of a young attorney too afraid to ask.

The boss went around the office and asked each of the medical malpractice attorneys to self-select a few files for me. You might rightly conclude that these were not the easiest cases in their file draws, nor those in the closest counties.

Within two months I was taking depositions in a medical malpractice case concerning a one-year failure to diagnose and treat lung cancer, when a spot that appeared on a routine chest x-ray was not appreciated. When surgery was finally done to remove the diseased lung, the pulmonary artery slipped out of the clamp and the man bled to death on the operating room table.

Everyone was sued. Internist, surgeon, assistant surgeon, anethesiologist, hospital. Everyone.

And it’s amazing what you remember from your first time, and the lessons (if you had good mentors, which I did) that carry through over the decades.

My marching orders were clear: No matter how much obstruction I faced at depositions by the battery of seasoned attorneys from the five law firms on the other side:

Keep asking questions, no matter what the other lawyer says.

Lawyers will object — don’t fight back. Just establish that the lawyer won’t allow the question to be answered.

Make a clear record of the obstruction.

Then make motions to bring back the doctors for continued depositions if they were recalcitrant in answering due to the antics of their lawyers.

Then actually bring them back for those continued depositions, even it’s for only one question and a few follow-up that need to be answered. Doctors are not happy when they have to take off half a day to answer just 10 minutes of questions. And their anger will be taken out on their own lawyer, who caused this to happen. That law firm will never do it to you and your clients again.

All the time, I was astonished that I was allowed to do this, and wondering if, at some point, one of those lawyers would point a finger at me and cry “fraud.”

I learned that it was OK to be inquisitive like a child, and to force witnesses to explain complex terminology as if I was a high school student. Because that might be all the education that some of the jurors have, and a real trial lawyer (not a baby one like me) might one day want to read it to those jurors.

In my first two years I tried two medical malpractice cases. And I’d completed over 100 depositions of doctors/nurses.

I was 28, and recognizing I might never have this opportunity again, took a year off to travel the world, knowing (or at least believing) that by that point I’d acquired the skills to be hired by reputable firms, and that no one would look at me and cry fraud. Because I had good training.

On return, I wasn’t certain what I would do, so I printed up some business cards, taped one to a blank piece of paper and xeroxed that onto good paper. I had letterhead, and I was in business for myself doing per diem work for other lawyers. Court appearances, depositions, and eventually trials.

I typed up reports on the Smith Corona I had used in law school. I filed papers myself. I made countless phone calls from courthouse pay phones, always carrying with me a roll of emergency quarters.

That was 1989. And the business I have today is, except for the technology, the same one — small firm practice doing personal injury (but not needing the per diem appearances and trials that consumed my first few years).

In this capacity I have represented people in big cases and small, famous (a client on 60 Minutes) and not (the vast majority). I’ve taken verdicts in every county in the area, and tried cases in both state court and federal. From the most mundane of tasks, to arguing in the Second Circuit. At the end of May, I am scheduled to be sworn in at the Supreme Court.

Along the journey I rented offices, hired (and fired) staff, and started this little blog (nine years ago). Many times I wasn’t really sure what I was doing, but sitting still wasn’t going to be part of it.

Today, I’m older than I ever was, but know that I am younger than I’ll ever be. So I keep moving, and if I get a chance, will continue to run marathons. It may be that one day I look back at these as the good old days.

The lessons along the way have filled this blog — on deposition and trial tactics, ethics, marketing, law office management, cases in the news, recent personal injury decisions, tort “reform” and much, much more. I rarely write about myself in this space — I’m not big into navel-gazing and if this blog was about self-promotion I’d have an audience of one — but I make an exception today.

It’s my anniversary. Or barversary. Or something. There must be a wonderful portmanteau to invent for such an occasion, but I just haven’t thought of it yet.

Happy anniversary to me. I think I’ll go have a beer tonight.