When we last met on this blog, I discussed the final two defense experts.

When we last met on this blog, I discussed the final two defense experts.

Tuesday, June 24th: The witnesses are done. All that’s left are summation, jury instructions, waiting and verdict.

In the morning I engage in one of my super-secret trial rituals, now exposed here for the world. I put on my wedding tie. All trial lawyers have superstitions or good luck charms.

I will be summing up last, after the two defense lawyers. It’s often said that the person that goes last has an advantage. But that person also has a problem: The jury has already heard a lot of lawyer talk. They are itching to deliberate. To speak with one another and finally get past the judicial admonition that they had previously heard not to discuss the case . Listening to lawyers speak on, and on, and on is hard. The trial attorney’s job is to make it interesting. To hold their eye and attention.

And that means notes must be kept to a minimum. If you’re going to read your summation you might as well just sit down now and save everyone the time, because no one will hear it. The attorney representing the leasing company goes on for an hour. We have a five-minute break and the attorney for the driver speaks for about 25 minutes.

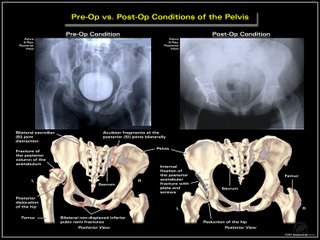

My turn. I start with a couple nuggets of trial testimony and argument I’ve prepared, working with the model of the spine, pelvis and hips in my hands to describe how the socket of the hip was pulverized in this car accident, and then move in to rebut the defendants arguments. Back and forth I weave from my prepared text to their arguments. Most of the time is spent dealing with the experts, and a large pad of paper on an easel is used for compensation suggestions. The main defendant had put his numbers up on the same pad just moments ago; since this is a damages-only trial he has no real choice. He then predicted I would ask for 4 or 5 million dollars, an amount that is clearly not sustainable in any appellate court. (See: How New York Caps Personal Injury Damages) That makes my job easier as I suggest more modest numbers, virtually the same ones I used in settlement negotiations. Numbers that an appellate court would find fair and reasonable if it came to that.

The jury goes out at 1:30. The defense then offers us a million. It is the first time since the accident almost three years ago they have made a bona fide offer. I did not respond kindly to their prior lowball efforts. But the offer today is still too low and we reject it.

Time to get lunch. And wait. Walk the halls. And wait. Watch 10 minutes of the trial next door. And wait. I once waited five days. There really isn’t anything quite like waiting for a jury verdict.

At 3:30 I find myself writing notes about the courtroom longhand in my trial book for later transcription to this blog. I have little else to do but think and write. And one of those thoughts is this: If the jury awards less than the offer I just rejected, will I even bother to put up these blog postings when it’s all over? While such an event might be entertaining for readers, it isn’t the kind of thing a lawyer would want to write about.

There has been one note. A request for certain evidence. They get it. We wait some more.

At 4:30 the jury returns with a verdict. The lawyers assemble. The jury enters. “All rise!” is shouted from a courtroom corner. We rise and wait for the judge and the reading of the verdict. And wait. And and then wait some more. You can hear the judge on the phone in the robing room. Two long minutes of standing and waiting and looking at the jury and wondering.

The judge finally enters and the verdict is read: $420,000 for economic loss and $850,000 for pain and suffering. Since summary judgment was granted in plaintiff’s favor in 2006, there will also be about $190,000 in interest, for a total of about $1.46M. There may be subsequent present-value reductions of portions of the verdict relating to future damages under a complicated formula that needs an economist’s brain to decipher.

The jury is quickly escorted from the courtroom. I get no chance to stand up and thank them for their service. And no chance to talk with them after they leave, as the court needs to address the issue of post-trial motions. I also need to retrieve some of the evidence and pack up my bags to leave. By then the jury is long gone. I don’t get the opportunity to ask them what they thought about various portions of the trial and the decisions that I have made, to tuck away in my brain for future reference.

As I leave the courthouse I am in wonderment that this case even went to verdict: The interest has been mounting for 20 months on what would surely be a substantial case. Of all the matters in my office, I thought this one was the most likely to settle.

And I silently thank my dad for teaching me to prepare all cases for verdict, and never for settlement. Since my training was in medical malpractice suits, and such cases rarely settle before trial, I’ve always shown up ready. And so that is the philosophy I use for my general negligence cases as well. I reflect on the lessons of my father and wonder which ones are being passed down to the next generation.

I head home to my family and take them out to a Mexican restaurant that the kids like. I order up a margarita. On the rocks. With salt. I’ve lost three pounds during trial, about normal for me, and I will now start to put it back on. I sit back and look at my kids and try to morph back into Daddy.

A month from now I am scheduled to start all over again.

————————————————————————-

Prior Posts In This Series: