The first time I saw Pete Seeger sing was in a driving rain storm. It was in Albany, 1981, and I was part of a university crowd marching downtown to protest the Springboks — the national rugby team of apartheid South Africa.

The first time I saw Pete Seeger sing was in a driving rain storm. It was in Albany, 1981, and I was part of a university crowd marching downtown to protest the Springboks — the national rugby team of apartheid South Africa.

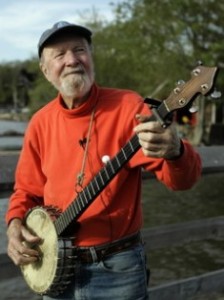

The skies opened up on us during the march. But there was Pete, banjo in hand, with supporters holding umbrellas over his head, singing. Through the eyes of a 21-year-old college student, he looked old even back then. This was the scene, as recorded by the New York Times:

ALBANY, Sept. 22— After a day of Federal court decisions, a bombing of the sponsor’s headquarters, arrests of radicals and mobilization of the city’s police force, the touring South African Springboks rugby team played a rain-drenched match tonight on a floodlighted field in Albany’s outskirts.

While the players scrummed and kicked in the mud, the shouts of 1,000 demonstrators confined to a knoll 100 yards away reached the field, which was surrounded by the police. Pete Seeger led the protesters in the African song ”Wimowey” and a local minister said, ”This will go down as one of the blackest Tuesdays in American history.”

I’m not going to sit here and say I agreed with every position that he stood for over the course of his 94 years. I can’t say that about anyone. But when a man stands up to the House Un-American Activities Committee because they are afraid of his music, it’s hard not to appreciate his strength of conviction in the First Amendment. He reportedly had this to say in 1955:

I am not going to answer any questions as to my association, my philosophical or religious beliefs or my political beliefs, or how I voted in any election, or any of these private affairs. I think these are very improper questions for any American to be asked, especially under such compulsion as this.”

You can actually see the testimony on Seeger’s own website.

But that doesn’t mean he was unwilling to tell this most un-American of committees a little bit about himself. He offered instead to sing the songs that the committee mentioned. They refused. He was blacklisted. He was indicted. He was convicted.

And the conviction was overturned, though not on First Amendment grounds, which were not even discussed. Today, that is the way most would have looked at the refusals to testify.

This is a fuller part of the inquisition before the committee:

MR. TAVENNER: The same occasion, yes, sir. I have before me a photostatic copy of a page from the June 1, 1949, issue of the Daily Worker, and in a column entitled “Town Talk” there is found this statement: The first performance of a new song, “If I Had a Hammer,” on the theme of the Foley Square trial of the Communist leaders, will he given at a testimonial dinner for the 12 on Friday night at St. Nicholas Arena. . . .Among those on hand for the singing will be . . . Pete Seeger, and Lee Hays-and others whose names are mentioned. Did you take part in that performance?

MR. SEEGER: I shall he glad to answer about the song, sir, and I am not interested in carrying on the line of questioning about where I have sung any songs.

MR. TAVENNER: I ask a direction.

CHAIRMAN WALTER: You may not he interested, but we are, however. I direct you to answer. You can answer that question.

MR. SEEGER: I feel these questions are improper, sir, and I feel they are immoral to ask any American this kind of question.

MR. TAVENNER: Have you finished your answer?

MR. SEEGER: Yes, sir.

MR. TAVENNER: I desire to offer the document in evidence and ask that it be marked “Seeger exhibit No.4,” for identification only, and to be made a part of the Committee files.

MR. SEEGER: I am sorry you are not interested in the song. It is a good song.

…

MR. TAVENNER: Did you hear Mr. George Hall’s testimony yesterday in which he stated that, as an actor, the special contribution that he was expected to make to the Communist Party was to use his talents by entertaining at Communist Party functions? Did you hear that testimony?

MR. SEEGER: I didn’t hear it, no.

MR. TAVENNER: It is a fact that he so testified. I want to know whether or not you were engaged in a similar type of service to the Communist Party in entertaining at these features.

(Witness consulted with counsel.)

MR. SEEGER: I have sung for Americans of every political persuasion, and I am proud that I never refuse to sing to an audience, no matter what religion or color of their skin, or situation in life. I have sung in hobo jungles, and I have sung for the Rockefellers, and I am proud that I have never refused to sing for anybody. That is the only answer I can give along that line.

I’m not going to write a full blown obituary for a 94-year-old man with a full life in the public eye. You can read any number of them circulating on the web in news reports. But this is a law blog, so I choose the legal angle. And from my standpoint, that means using words and symbols in order to argue a point.

Above any one particular political position he held was the pursuit of non-violence and that people should talk to each other. The inscription on his banjo read:

Above any one particular political position he held was the pursuit of non-violence and that people should talk to each other. The inscription on his banjo read:

This machine surrounds hate and forces it to surrender.

Back in 1979, the late Harry Chapin — one of many, many singer-songwriters he influenced — wrote a tribute to Seeger called Old Folkie, that you can find on YouTube, that starts like this:

He’s the man with the banjo and the 12-string guitar.

And he’s singing us the songs that tell us who we are.

When you look in his eyes you know that somebody’s in there.

Yeah, he knows where we’re going and where we been

And how the fog is gettin’ thicker where the future should begin.

When you look at his life you know that he’s really been there.

Americans of all stripes have much to be grateful for in the Seeger lessons. Because free speech affects all of us, regardless of political bent. It’s worth repeating, from his 1954 testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee:

I have sung for Americans of every political persuasion, and I am proud that I never refuse to sing to an audience, no matter what religion or color of their skin, or situation in life. I have sung in hobo jungles, and I have sung for the Rockefellers, and I am proud that I have never refused to sing for anybody.