It isn’t often that someone emails me out of the blue and asks me to commit a misdemeanor. So I guess this wasn’t just another day.

Welcome to another edition of: outsource your marketing = outsource your ethics. Today, perhaps, we can add to that equation that you might end out surrendering your money, license and liberty as well.

The email came to me from a Utah digital marketing firm called Lead PPC, from its CEO Grant James. I get pitches from marketeers all the time (“first page of Google!!!”) and generally just delete before reading, but I look sometimes to see if there’s any new scam under the sun.

The pitch was simple: The company would use the names of other personal injury attorneys as keywords for Google and my name would pop up in an ad. In other words, they want me to trade on the names of my “competitors” (a/k/a friends and colleagues). This was the emailed pitch:

By staying away from the expensive $100+ cost per click keywords, we get right to the good stuff that is cheap, targeted, and needs help now. Mostly, people are searching for the names of your top competitors who are advertising on radio, tv, and billboards. We show up above them on Google and Bing, and they call us instead of them.

Whoa. Now I may not always be the sharpest knife in the block — just ask my kids — but I do know that trading on the name of someone else is, what we call in legalese, a big, fat, hairy, ugly no-no. This is New York’s Civil Rights Law §50, also known as the right to privacy (and elsewhere, in various forms, the right to publicity):

A person, firm or corporation that uses for advertising purposes, or for the purposes of trade, the name, portrait or picture of any living person without having first obtained the written consent of such person, or if a minor of his or her parent or guardian, is guilty of a misdemeanor.

And in Civil Rights Law §51, there is a private right of action, and this includes both compensatory and punitive damages. In other words, I could be sued by the people whose names I’ve appropriated. And unlike other suits against me, this one could actually have merit.

In addition to the prospect of criminal and civil problems, there is also the prospect of action against my license under the Code of Professional Responsibility for false and deceptive conduct (Rule 7.1(a)(1)), implying that the better-known lawyer is associated with my firm (Rule 7.1(c)(2)) and using “hidden computer codes that, if displayed, would violate these Rules” (Rule 7.1(g)).

Figuring that my understanding of what he suggested might just, perhaps, be the result of a poorly written email, or maybe that I didn’t understand the technology, I replied to Mr. James seeking clarity:

Hi Grant.

I read through your email and didn’t understand something:

Mostly, people are searching for the names of your top competitors who are advertising on radio, tv, and billboards. We show up above them on Google and Bing, and they call us instead of them.

What does this mean?

Simple enough, right? But his response was to make clear that I had it right the first time, that this was a dishonest, misbegotten, bastardization of legal marketing. He responded by giving me the names of prominent Texas trial lawyers he had misappropriated:

Hey. Yeah sorry if this was a little vague or confusing.

An example would be like in Dallas and Houston where we spend most of our budget on terms related to Jim Adler, Brian Loncar, ijustgothit.com, radlaw, and other terms for competitors.

What happens is that people hear a radio commercial and they can’t remember the website, so they search for what they can remember about the lawyer.

So if a guy searches for Brian Loncar, we know that they were most likely in an accident. If we rank for #1-2 on PPC, especially mobile, they click on us and call in.

A prospect typing in the name of a competitor term as opposed to “personal injury lawyer” is a much hotter prospect and further down the buying path. Additionally, these terms are much cheaper and less competitive than the broader terms everyone is bidding on and pushing up the prices.

The strategy works best in larger cities where law firms are advertising heavily on radio, tv, etc.

Texas, we have a problem.

Leaving aside the marketeer for a moment, what lawyer would do such a thing to another? I wanted to know, but since I’m in New York the Google ad words didn’t pop up in my market when I searched.

But, funny enough, I happen to know ace Dallas criminal defense lawyer blogger Mark Bennett. And Mark has written his fair share of postings about shady marketing tactics.

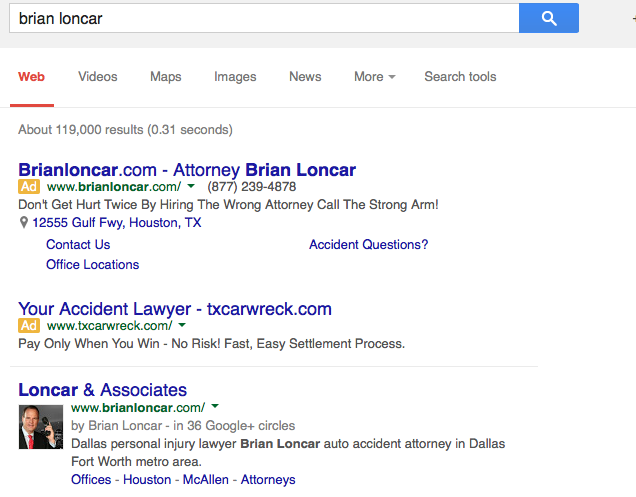

So he Googalized those more prominent names that Grant James had kindly told me he had misappropriated, and up popped the website (txcarwreck.com) of attorney Ben Abbott in the Google ads. You can see one of the to the right, where Brian Loncar was Googled. Bennett has screen shots of others.

You will notice that Bennett searched only for the name, and didn’t add lawyer, car accident, or any other popular buzzword. Just the name. And up pops Ben Abbott’s ad.

As it happens, swiping the name of another person in order to exploit it is also a problem in Texas. It sure looks like Ben Abbott can be sued, and I’m guessing Grant James and his SEO company as well.

Now I’m also going to guess, simply because I fancy myself a kind and beneficent person, that Grant James is utterly ignorant of the law. I think I’m being charitable when I wrote that he probably knows that swiping the names of others to trade on them is a pretty scummy black hat tactic, but that he doesn’t know the legal ramifications. Or he knows but just doesn’t care.

But what would be the excuse of attorney Ben Abbott?

While I know that black hat marketing techniques go on, and have written about them in the past, I never really guessed it would come at me in such a bold and obvious way.

Who, I wanted to know, would he target? So I asked and he responded:

I would need to work together with you to put together a list of 15-20 of the top competitors in NY. It would be the same guys who advertise on radio, tv, and billboards.

So then I moved the conversation to problems with his scheme, with a nice open-ended query to get his thinking, to see how he could justify this:

I don’t know, Grant, the whole thing about using the names of other lawyers to promote myself doesn’t really sound kosher.

What came back was a very long email about how Google operates and what Google allows and doesn’t allow and Google this and Google that, as if Google was a law of some kind and could be waved in front of judge and jury as a defense.

To Ben Abbott, who should know better, I asked:

Mr. Abbott:

I’m writing an article about your using the names of other Texas trial lawyers as part of your advertising. This includes Jim Adler and Brian Loncar.

When their names are Googled, your ad pops up. Would you care to comment about why you think this is acceptable marketing?

Thank you.

He hasn’t written back yet. If he does, I may update this.

This is, by the way, part of the Wild West of marketing. A year ago in Wisconsin, under presumably different laws, a court held that stealing someone’s name to use as a hidden advertising keyword might past muster in a civil suit, as in that state (unlike New York) there was apparently no statute. There was no word in Eric Goldman’s Forbes column about the ethical implications. (Update: Under Florida law, this is not an ethics violation. I think is should be.)

But I think the message is pretty clear that, once again my friends, when those marketeers come-a-callin’, you had best remember that they become your agent when you hire them for marketing. Marketing is part of attorney ethics. If you elect to outsource your marketing then you have outsourced your ethics. And reputation. And possibly your bank account and liberty.

It sucks to be a test case.