Over the weekend, I guest-blogged at Kevin, M.D. It is republished here for wider distribution:

————————

Last week I was struck by a post by Dr. Saurabh Jha at Kevin, M.D., about his views of the jury system — as some of his comments mirrored things I’ve said to juries in the past.

Some things he got right, which go to the core our civil justice system. Some things, however, not so much.

His perspective comes from growing up in India, which doesn’t exactly have the most efficient of justice systems. And because of a lack of confidence in that system, folks sometimes take matters into their own hands. Like burning people alive:

One of my most harrowing memories in India as a child was when I saw a mob pour kerosene on a bus. My grandfather pulled me away before the bus was set alight, but I knew what was happening. The mob had tied the driver and conductor to the steering wheel. The mob was angry because the bus had crashed into a pedestrian fatally injuring her. The mob formed spontaneously and dispersed spontaneously. Mobs are as capricious as India’s legal system.

Dr. Jha writes because this concern over vigilante justice isn’t limited to crimes and motor vehicle fatalities, but to something that I’ve never heard of in the United States — retribution against doctors for bad results:

…doctors face a new tide – mob attacks for undesirable patient outcomes. The strike by doctors in Calcutta in protest of a junior doctor seriously injured by an angry family of a seventy-five-year-old patient who passed away, is just the tip of the iceberg. There’s more trouble brewing.

While we see vigilantism from time to time here when crimes are committed — think relatives seeking revenge on a rapist or killer — rarely do we see if for matters generally handled in the civil system such as bus collisions. And certainly not for medical malpractice, which is the heart and soul of his concerns as he discusses a family member’s decision on whether to go into medicine.

So Dr. Jha brings a different perspective. And the first part of that perspective is that there’s a price to be paid for a justice system that works to sift through and clarify the facts behind an incident in a manner that doesn’t involve guns, knives, fists or kerosene:

It was only years later that I understood the price of stopping mobs. When I arrived in Philadelphia for my medical training, I couldn’t afford a car because I couldn’t afford auto insurance, which was unaffordable because the costs of litigating auto-accidents were so high, which were high because of the generous compensation for a range of injuries including the nebulous “whiplash.”

Leaving aside his assumption that costs were high because compensation was “generous” for “nebulous” soft tissue injuries, was this increased cost worth it? Dr. Jha is clear in his opinion that, because mobs are more likely to exist when the justice system isn’t trustworthy, it is definitely worth it. And society becomes safer as a result:

Mobs attempt to correct for failures of institutions to make systems safer. Though mob violence is a blunt tool, unhelpful at making systems safer, their expression signals a void – the paucity of confidence in civil courts. If patients’ families had confidence in the legal system and were sufficiently compensated, over time they’d be less likely to be violent against doctors when they perceived real or imaginary medical negligence. Compensation doesn’t bring back the deceased, but it’s an apology of sorts. Though dreadfully cynical to say – money is balm to the grieving soul. In its absence, retribution rears its ugly head. Mobs exact retribution in lieu of compensation.

This mirrors, in part, some of my standard spiel in voir dire — particularly when I see a run on the room with all kinds of BS excuses to get out of jury service. Our system of justice, while imperfect in that money can compensate for, but not heal, an injury, stands as a substitute for the alternative of vigilantes.

Dr. Jha is likewise clear in his opinion that justice isn’t cheap, because safety costs money:

The mob problem faced by doctors in India won’t be cheap to solve. The government must invest a fair amount in courts, medical malpractice insurance, and hospital infrastructure. Due process is expensive. Safety costs.

But there’s a second part of his posting that also caught my eye, and that was the assumptions that he used about costs, particularly with respect to medical malpractice. He used at least three well-worn tropes, just assuming them to be true:

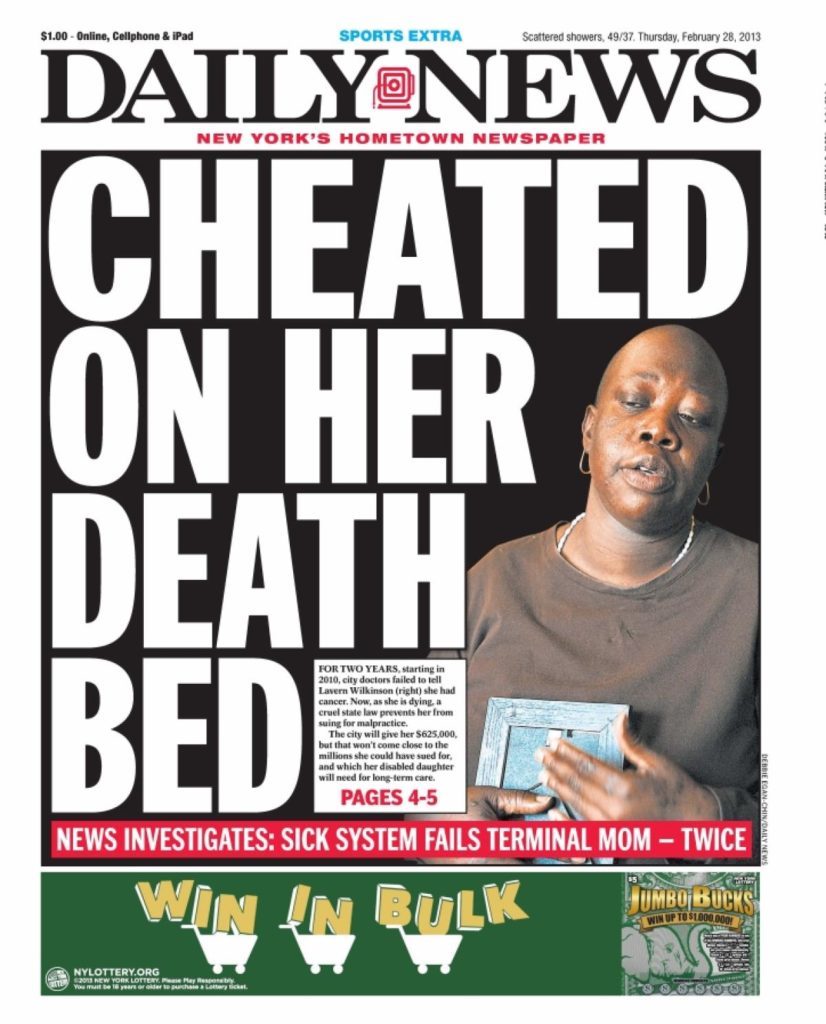

The United States is famously litigious, particularly in medical malpractice, where millions are awarded for bad patient outcomes which may or may not be caused by negligence.

This one statement isn’t accurate on multiple levels. First, one really can’t bring small medical malpractice cases because cases are expensive to bring. By definition complex cases must be larger than simpler matters. Who’s going to risk $50,000 in expenses and a couple hundred hours of time on a case with a $100,000 value? For smaller matters, the medical community enjoys de facto immunity.

Second, money doesn’t get awarded for cases not caused by negligence. While a jury may, from time to time award damages on insufficient proof (and, conversely, sometimes tosses out a case despite overwhelming proof) a judge can toss that verdict if the facts aren’t there to support it. And after that, there’s an appellate court to do the same. There are, therefore, two additional layers of protection against what Dr. Jha merely assumes to be true.

Next up is the trope about “defensive medicine” driving up costs due to the fear of litigation:

The net effect of litigation is defensive medicine where doctors over-order tests to avoid lawsuits. Defensive medicine has made healthcare costlier.

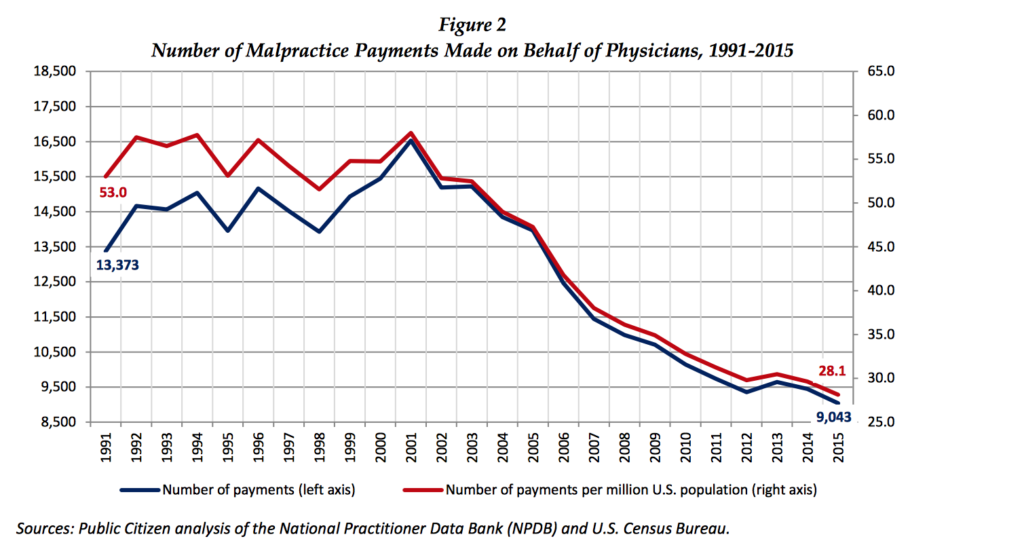

This was demonstrated in an empirical study to be false. In 2003 Texas passed a law that capped malpractice payments at a paltry $250,000, with the predicable result that fewer cases were brought and that doctors would feel “safer.”

So fewer “unnecessary tests,” right? Less “defensive medicine?” Wrong. Medicare spending in Texas went up 13% more quickly per beneficiary than the national average. The idea that fear of malpractice cases was a driver of increased medical costs was demonstrably false.

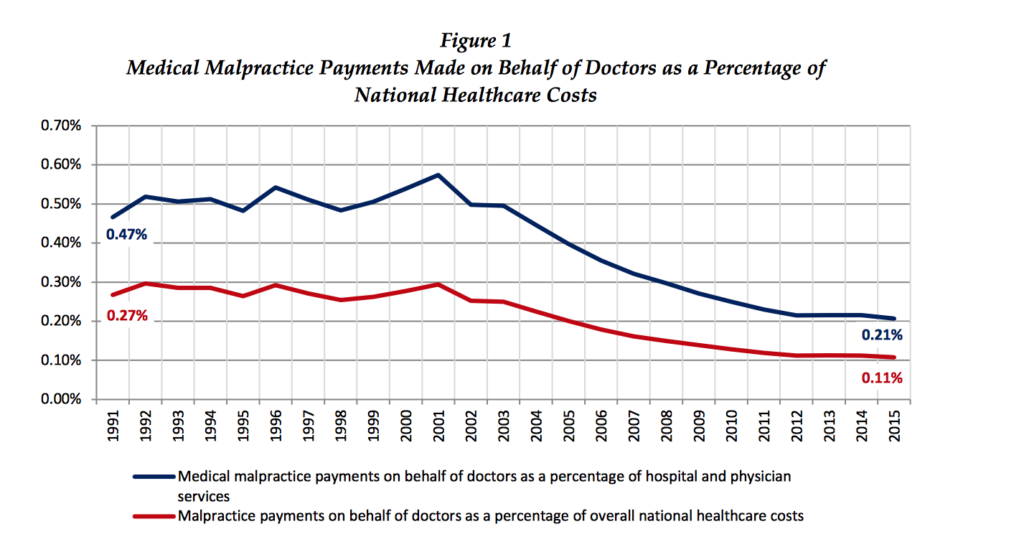

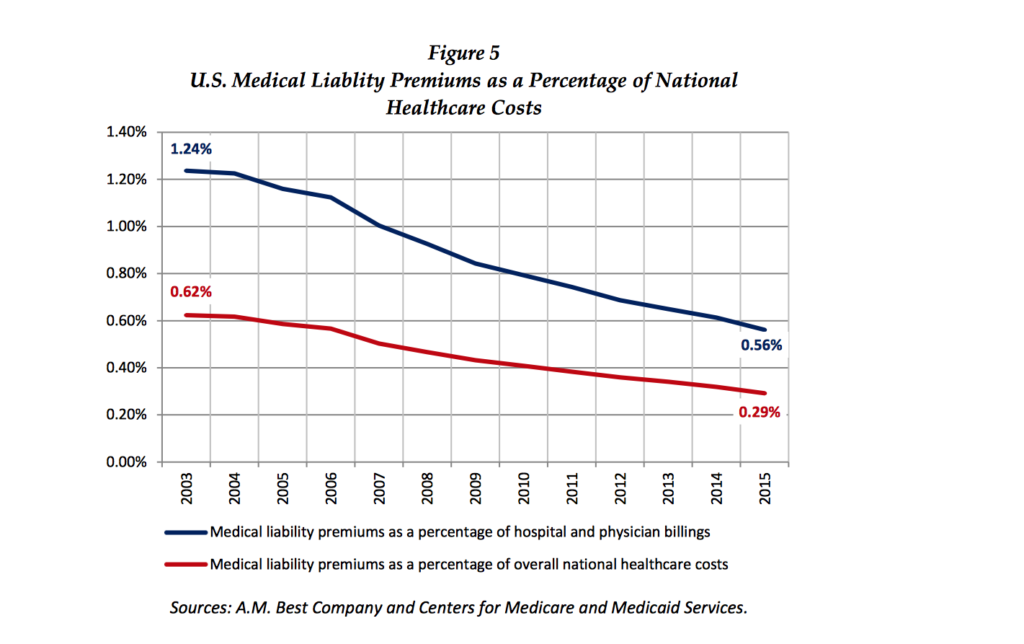

America, unlike every other westernized country, doesn’t have universal medicine. It is fee for service. There is a financial incentive to order more tests. Whether that is a driver of our escalating health care costs I don’t know, but it certainly isn’t a fear of malpractice suits, which are just 2.4% of our overall healthcare costs.

So, in response to Dr. Jha, you got it partly right, in that a functioning and trustworthy justice system beats the hell out of vigilante justice (which has its own costs). And it makes society safer. But you missed the mark on some of your underlying assumptions about our justice system. Those well-worn tropes that you (and many others) use is something to rethink.