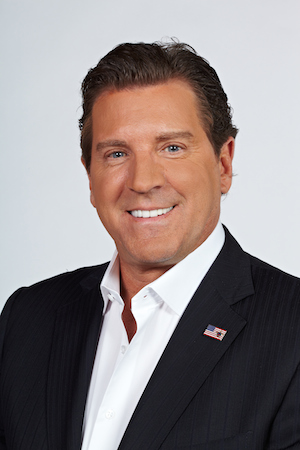

News junkies know that yet another Fox News anchor has been shit-canned over allegations of sexual harassment, this time it being anchor Eric Bolling. Fox has “suspended” him for allegedly sending lewd texts and photos to colleagues.

But I’m not here to deal in the actual details, but rather, the $50 million suit he has filed against his accusers in New York state court, and the procedural quirk that allows him to make that claim despite New York’s apparent prohibition on doing it.

You see, Bolling’s attorney didn’t file a Summons with a Complaint, but rather, a Summons with Notice. To us New York lawyers, this is a very significant procedural issue. The brief document is here: EricBollingSummonsWithNotice

A Complaint has details in a defamation case, setting forth actual words that were written or uttered that are claimed to be false and injurious. This Summons with Notice crap, does not. It’s substance merely states:

The nature of this action is for damages and injunctive relief based on defamation arising from the defendant’s efforts to injure the plaintiff’s reputation through the intentional and/or highly reckless publication of actionable false and misleading statements about the plaintiff’s conduct and character. As a result of the defendant’s actions, the plaintiff has been substantially harmed.

While it is legal to start a suit this way, it is most certainly not the way lawyers practice. He now has just 20 days to file the Complaint or risk dismissal.

But time wasn’t a barrier for any of this — he could have waited to draft a Complaint if it had merit — so why start suit in such a crappy fashion?

My theory:

There will be no real lawsuit to follow. This was rushed out the door to intimidate others from stepping forward and grab press. Put a big whopper of a number in the filing — in this case $50M — and people who may claim to have been harassed may simply say I don’t need this crap.

There isn’t any other reason I can think of. If it is brought to the attention of a judge, s/he is likely to simply strike it. But the damage has already been done.

But wait! What about that mammoth $50M number? Regular readers know that I have railed against those who put ad damnum clauses into their pleadings. New York (thankfully) outlawed this practice for personal injury cases back in 2003 (and defamation constitutes personal injury). It used to apply only to medical malpractice cases, but in 2003 was changed to all personal injury cases. CPLR 3017(c) states:

In an action to recover damages for personal injuries or wrongful death, the complaint, counterclaim, cross-claim, interpleader complaint, and third-party complaint shall contain a prayer for general relief but shall not state the amount of damages to which the pleader deems himself entitled.

New York’s Grand Poobah of Procedure, the late Prof. David Siegel, thought a monetary sanction should be levied. In his authoritative treatise on New York practice he wrote:

“Some cases have held that a violation of the CPLR 3017(c) pleading restriction can be cured with a mere amendment striking the reference to the demand, but the imposition of a money sanction in an appropriate sum might better implement this aspect of CPLR 3017.”

But Bolling’s lawyer may have discovered a loophole to grab that press. Because CPLR 3017(c) doesn’t list Summons with Notice as one of the documents that prohibits the ad damnum clause. Here it is again with emphasis added:

In an action to recover damages for personal injuries or wrongful death, the complaint, counterclaim, cross-claim, interpleader complaint, and third-party complaint shall contain a prayer for general relief but shall not state the amount of damages to which the pleader deems himself entitled.

And yet, the Summons with Notice (CPLR 305) requires a prayer for relief (“shall contain”) except in medical malpractice cases:

(b) Summons and notice. If the complaint is not served with the summons, the summons shall contain or have attached thereto a notice stating the nature of the action and the relief sought, and, except in an action for medical malpractice, the sum of money for which judgment may be taken in case of default.

So it appears that when CPLR 3017(c) was amended in 2003 to forbid the placing of a specific demand for relief in a Complaint, the Legislature forgot that CPLR 305 requires it in a Summons with Notice.

We lawyer types have a word for that discrepancy: Loophole. I don’t know if Bolling’s lawyers knew it existed when they drafted this document, but there it is anyway. But when I sat down to write about the odd way this suit started, I certainly didn’t realize it. While I came to critique the way this suit was started that’s what I found instead.

A loophole.

And one that the Legislature should fix in the next legislative session by amending both CPLR 305(b) to add all personal injury suits to the actions that prohibit the demands for relief, and adding Summons with Notice to the list of documents that prohibit it in 3017(c).