The footrace race ranged 340 miles across the South. Kim McCoy, a 37-year-old nurse in NYC, had already finished 270 miles of it. Then the SUV hit her at an uncontrolled intersection and she lost her leg. Apparently, she’s lucky she didn’t lose more.

This post hits three different spots for me: As distance runner (but not ultra marathons), as a race director who deals with runner safety, and as a personal injury lawyer that needs, when the times comes, to weigh the issue of liability for an event that may have substantial risks.

While that’s a lot to unpack, the gripping story by Matthew Futterman at the New York Times isn’t complex: This is not your local 5K or even your local marathon. The race might take you a week to finish, and that assumes you are in top notch shape. You bring little with you in a small backpack and buy food and water as you travel. You sleep wherever. And you don’t get to see a course map until a few hours before the race starts.

The event is the brainchild of legendary race director Gary (“Lazarus Lake” Cantrell who created the Barkleys Marathons which is so (in)famous among runners there’s even a “delightful documentary” on it, subtitled “the race that eats its young” because so few ever finish the 100+-mile grueling event through unmarked woods. Mostly off-trail. Many years there have been no finishers at all. These were the same woods that Martin Luther King’s killer, James Earl Ray, escaped from to prison to, and he got only 8 miles in 55 hours. The race is designed for failure.

So races that seem impossible, that stretch the bounds of what humans were once thought capable of doing, are his sweet spot.

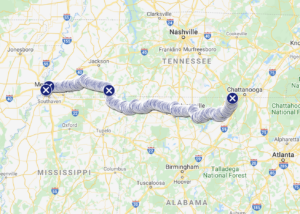

Thus came the 340-mile race — West Memphis, Ark., to Castle Rock, Ga. — where Kim McCoy was run down by an SUV at that uncontrolled intersection. This isn’t a race with closed roads, or fancy directional markings, or even permits. Here’s the map. Go run. Good luck. See ‘ya.

But when you try to stretch the bounds of human capacity you also run headlong into injury, danger and potential death. Exhaustion makes everything more difficult and dangerous. It’s easy to miss a simple rock or root on a trail, or a car on a road, when bleary-eyed, dazed and discombobulated.

This problem came into full appreciation when McCoy tried with another runner to cross Highway 72 near Huntsville, because that is the way the route went.

They made it to the median, then thought they saw an opening. Halfway across, Grinovich saw a flash of light and pulled back. McCoy kept going. He heard a crack and was sure she was dead. Then he ran to her and heard a moan. Somehow, after being sent airborne down the highway, she had hit feet first and rolled, rather than crashing on her head. As she tumbled, her backpack had cushioned the impact.

Tucked into that NYT story of McCoy’s race across the South comes this speculation about liability for injury — after all, race director’s know that the participants may not be thinking straight and more in danger:

Who bears responsibility for McCoy’s accident is a question lawyers and insurance companies may have to decide.

She has not filed a lawsuit, but has retained a lawyer, even though she signed a waiver releasing Cantrell from liability before the race. Waivers don’t allow race organizers to act with negligence, the definition of which can be subjective.

Now I’m not going to opine on Alabama law — or even which state’s law applies since McCoy and Cantrell live in different states and the incident happened in a third. Or did it? The drawing of the map, after all, may well be the “incident” itself.

I’m sticking here with general principles (as they would apply in New York). Your mileage, as the old saying goes, may vary.

The doctrine of assumption of risk, which I have written about often, generally precludes suit against an event organizer when the risks are known and appreciated. Sometimes referred to as the “baseball rule” for spectators that are injured by foul balls or flying pieces of broken bat, it holds that you have assumed the risks inherent in the activity.

Perhaps, if the race demanded that participants do something illegal — like demanding that runners cross an interstate highway, one might be able to raise the argument that assumption of risk doesn’t apply. Race participants don’t, after all, get a map well in advance of the race and have an ability to check out the details. And even in this kind of race, a reasonable participant wouldn’t expect something illegal.

But that isn’t likely given the photo of the crossing in the Times and the comment by Cantrell that pedestrians were permitted. If pedestrians were legal here, it would be unlikely to to be a successful suit.

The key for any sporting event director is to actually show, as best you can, what the anticipated risks are so that they are appreciated. This not only helps to immunize from suit, but more importantly, actually informs people of the types of dangers they might expect so that rookies don’t errantly step into an event they are unprepared for.

I do this with the disclaimer for my own race. (I never understood those disclaimers that use unreadable ALL CAPS legal gibberish to help a participant appreciate risks.)

The story of McCoy’s incident and the loss of her leg is awful. But it isn’t likely that a lawsuit would be successful against the organizer of the race.